“Once you’re in the circus, it’s hard to get out.” Martha Wainwright on Growing Up Among Artists

Fights, Silences, and Music During a Tumultuous Year in Manhattan

My dad’s work comes first. Nothing else matters to him as much—not his partners, not his children. I knew this back then, and I know it now. The year I spent with Loudon Wainwright III involved lots of fights and lots of silences. I learned to lie, and I imagined my dad lied, too.

We lived in an apartment on Twenty-First Street, and I attended Friends Seminary school five blocks south, on Sixteenth at Third. In contrast to my all-girls school in Montreal, Friends Seminary was coed, and more liberal and artsy than I was used to. I convinced myself it was also attendance optional. Like any proper fourteen-year-old, I hated myself. And why not? I was out of my league with these Manhattan kids. I couldn’t even spell the word Manhattan.

Despite being a little less mature than some of my classmates, I quickly learned the ropes. Not with sex—I had no confidence in that department and was a little bit of a prude—but I was soon hanging out with the older kids. I think I was entertaining to them. I started school an angry kid and came out a year later a street-smart teenager.

My new best friend was a girl named Marissa. She was a year older than me and she was both very beautiful and stunningly miserable. Under her influence, I gave up clownish outfits in favor of whatever Marissa wore. Long Indian skirts that hugged her small waist and hourglass hips and turtlenecks that fit tight to her beautiful large breasts. Not quite as effective on me, or so I felt.

Both of us, for different reasons, had little parental supervision. Her father was absorbed by the demands of his new, younger family and his work as a top psychiatrist, and her mother was in Paris. My own father was clueless about how to set boundaries, and my mother was crossing her fingers that we would manage as she and Anna began to tour again. On the one hand, my dad made me do the dishes, since, as he pointed out, he paid for the food, and he also yelled at me to do my homework. On the other hand, he would let me stay out late because he was gone himself. He really had no idea what he was doing. No doubt he had girlfriends he wanted to see, but I think he also stayed out sometimes to get away from me.

As a kid, I listened a lot to my dad’s music, trying to find him. To get to know him. I was a big fan of his songs, and often when I was alone, I would play his records on repeat. I had learned to do this because my mother did it, too. She had all his records and had been the one to first play them for me. She was very moved by some of his songs, and by his voice, and I felt proud of him, too. I would bend my ear searching for mentions of me in the lyrics, along with references to my mother and brother. His songs felt like proof that I existed. That I was here. That I was real. That I had been born. It felt sometimes as if I were singing them, as if they were my story, too. But they were not my story, and there were a few times I was deeply disappointed and hurt by his songwriting.

My dad wrote a couple of songs about the year the two of us spent together. One of them, “Hitting You,” starts with lyrics about how he once hit me in the back seat of the car when Rufus and I were little. Then it moves on to how he wants to hit me again but stops himself:

Long ago I hit you

We were in the car, you were crazy in the back seat

It had gone too far

And I pulled the auto over and hit you with all my might

I knew right away it was too hard and I’d never make

it right. . . .

These days things are awful between me and you

All we do is argue like two people who are through

I blame you, your school, your mother, and MTV

Last night I almost hit you

That blame belongs to me

(The other song is called “I’d Rather Be Lonely,” and I’ll tell you more about it a little later. That one hurt more.)

The year of discontent my forty-four-year-old father spent with his fourteen-year-old daughter was one he hoped to forget but that I still remember fondly. I kept my dad from what he really wanted to be doing, which was music and being by himself, which tortured him as much as anything I got up to. But I had fun smoking pot, riding the subway at night, and meeting all these different, mostly rich, sometimes famous kids (Susan Sarandon dropped her children off at the seminary every morning) who lived in lofts in SoHo or big apartments on the Upper East Side. I had my first aching and, of course, unrequited crush that year, on a senior who lived in a brownstone in Brooklyn Heights. He was tall and good-looking and he was madly in love with Marissa. Deep down, I understood why. I was in love with her, too.

Having never spent so much time together, my dad and I remained uncomfortable and shy with each other. But even though I was a shit—which at that age was my job—I also really liked being around him and my sister, Lucy, and her mom, Suzzy, and that whole side of my extended family. Suzzy and Lucy lived in the West Village, and I would go over for dinner sometimes or for a girls’ night when Dad was away. My late grandfather’s much younger second wife, Martha Fay, still lived in the apartment where most of my childhood New York City visits were spent.

His songs felt like proof that I existed. That I was here. That I was real. That I had been born. It felt sometimes as if I were singing them, as if they were my story, too.

His first wife, my maternal grandmother, was Martha Taylor Wainwright, and one of Loudon’s two sisters was named Martha, too, though she was always called Aunt Teddy. (I know it’s crazy—four Marthas in one family!) The apartment, which she shared with her daughter, Anna—my aunt, though she is ten years younger than me—was filled with books and pictures; Martha Fay is an incredible person and a great cook, who took great care of me. Her place was a home away from home, and remained that way for many years.

Suzzy was a singer, too, and still is, one-third of the Roches, a New York–based folk act that her big sisters, Maggie and Terre Roche, had started in the 1970s, but that really took off when Suzzy joined a little later. You think it would be awkward between us, because Loudon had left my mother for Suzzy, or at least that’s how my mom framed it. (I could ask Suzzy, but I wouldn’t want to put her on the spot. I do remember as a kid finding naked pictures of her, and pictures of her sitting on my mom’s couch in my parents’ house in Woodstock. Putting two and two together is a part of growing up.)

Even though Lucy was six years younger than me, we had become close over the years of summer visits, and it had always been a little sad to leave each other at the end of a vacation, especially for Lucy, who was an only child and liked having siblings around.

Also that year, I became more like my father, as if the DNA in me that came from him started to wake up, almost like a switch got turned on. Just by being around him and that side of my family, I felt like I had added facets to my life and my personality. It’s hard to explain, like I grew new feathers or spots. I can only imagine how much more I would be like him if we’d had a little more time together—a little more time to learn how to be together. It maybe would have made things easier between us, and for me, in the long run.

Rufus and I had always been more influenced by Kate than my dad. When my brother and I were young and went to visit Loudon on Shelter Island (or as Lucy calls it, Tension Island—because my dad is tense in many ways), he’d try to impose his way of doing things on us. He wanted us to have summer jobs, to make our own money with paper routes and such, whereas Kate didn’t necessarily believe in pushing kids in that way. She wanted us to do well in school, learn to play instruments, and eventually write songs or lose ourselves in books and art or whatever. My father is disciplined; he practices and exercises according to a daily routine. It keeps him sane. He is also punctual, either right on time or a bit early, whereas I’m always late.

I disappointed my father more than once being late, making him wait at a restaurant for fifteen minutes, half an hour, or more. Rufus has a great song about Loudon called “Dinner at Eight.” If I had written the song, it would be called “Dinner at Fucking 8:45” and it would have told the story of an older man waiting impatiently for his flaky daughter to show up for a strained dinner date. Why did I do that so often to the both of us? Why would I leave Brooklyn at 7:45, seventeen subway stops away from his apartment, already guilty because I knew it would take an hour for me to get there and that Loudon would be angry? I was most likely stoned and he most likely knew it. (Rufus also has a song called “Martha” that laments the fact that I never call him back. So you can see the reputation I have in my family.)

Maybe I tortured my dad (and sometimes still do) because I was mad at him. Mad at him for almost denying my existence and for being so impatient with me as a teenager. For being so good at what he does and for committing his life to his art without compromise. That must be it. I’m a little jealous—of his freedom, his confidence, and his more disciplined approach to his career.

Some good things came out of that year I spent with my dad.

A math teacher helped me identify my life path. I was good at math and, like most of my teachers, she was disappointed that I had lots of potential but not much of a work ethic. One day she got so frustrated, she blurted out, “What do you want to do all your life—sing and dance?” I don’t think I responded, but then and there, I quit worrying about what I was going to be or do when I grew up. “Sing and dance”—it had a ring to it. I had been onstage singing and dancing for years, but it had never occurred to me that I could do it for a living. Because my parents did it, I didn’t see it as glamorous, and had thought I would do something else. But it was sure easier than calculus.

If you’re an artist, your kids are bound to end up artists, too. To put it another way, once you’re in the circus, it’s hard to get out.

_________________________________________________________

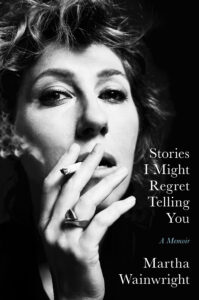

Excerpted from STORIES I MIGHT REGRET TELLING YOU: A Memoir by Martha Wainwright. Copyright © 2022. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Martha Wainwright

Martha Wainwright is an internationally renowned singer-songwriter, with over two decades of industry experience. Critically-acclaimed for the rawness and emotional honesty of both her vocals and lyrics, her albums include: Martha Wainwright (2005); I Know You're Married But I've Got Feelings Too (2008); Come Home to Mama (2012); the JUNO-nominated Songs in the Dark (2015), a collaboration with her half-sister Lucy Wainwright Roche; Goodnight City (2016); and her latest album, Love Will Be Reborn (2021). She is also an actress and was featured in Martin Scorsese's Aviator and the recent HBO special, Olive Kitteridge.