Once You Start Mushing, There’s No Going Back

Blair Braverman on Racing Sled-Dogs and Embracing the Pack Lifestyle

Dogsledding has always lived through its stories.

The sport is mysterious. Mushers live in some of the coldest, most remote places in the world. They don’t have neighbors; they spend more time with dogs than with people, and they like it that way. Even the most visible mushing events—long- distance races like the Yukon Quest and Iditarod—happen out of the public eye. Mushers and dogs head into the wilderness, then emerge days or weeks later. What happens out there? Only the team knows, but most of the team can’t talk.

So it’s up to mushers to tell their stories. We gather around campfires and wood stoves, warming our hands and recounting the trail. Stories about moose and ground blizzards, ice bridges and northern lights. Stories about every dog we ever loved.

He found me on the tundra.

She knew not to cross the river.

Never felt wind like that in my life.

As a kid in California, I got hooked on the stories. I lived in the dry, sweltering Central Valley, so the idea of cold alone—let alone a combination of cold and dogs—seemed like magic. I’d stare at photos of expeditions, malamutes, and wooden sledges, and wonder how it would feel to be surrounded by ice. I read Gary Paulsen and Farley Mowat, watched Balto and Iron Will. And when I was old enough, I moved to the Norwegian Arctic to learn to dogsled myself.

For a long time—as most people do, when they come to mushing—I helped with other people’s dogs. I scooped poop, trained yearlings, and worked as a tour guide. I loved the sport, but figured I would always be stuck on the outskirts; as a freelance writer and journalist, my life didn’t have the kind of stability that a dog team requires.

Pretty soon our whole life was dogs. All I wanted to talk about, think about, was the dogs.

And then I met my now-husband, Quince Mountain, in grad school. He was a horse wrangler, a child of northern Wisconsin who lived in a hand-hewn log house and had taught cold-weather survival. When we graduated, I moved to his homestead in the Northwoods. All of a sudden, I was rooted—and in a cold place, no less. It was the kind of life where I could have sled dogs. Quince wasn’t a musher, but he was game.

We adopted our first six dogs in 2014, a small team for exploring the winter woods. A year later, we took over a team of 15 dogs from a musher who was retiring, and it wasn’t long before Quince was as hooked as I was.

Pretty soon our whole life was dogs. I woke up planning what I’d make for their breakfast; I fell asleep imagining where we would run next. There were hours, days even, when nothing existed but the shifting sled runners, the gentle puffs of breath. It was the only world that mattered.

All I wanted to talk about, think about, was the dogs. (All any musher wants to talk about is their dogs.) So I started sharing pictures of them on Twitter, little anecdotes. It felt self-indulgent, like pulling photos from my wallet and showing them to anyone who was too polite to back away. Ifigured people could just ignore me.

But to my astonishment, an online community started to form around the team. These were people who loved animals and nature, who appreciated stories. The most moving part of it all, to me, was how they came to know and love the dogs—Hari and Jenga, Grinch and Jeff and Flame. Loved them and drew strength from them, just like we did.

Fans of the team started calling themselves the Ugly Dogs, after someone told me to Go back to your ugly dogs—and as Quince says, the Ugly Dogs are the salt of the earth. They support each other through tough times, volunteer at events, send mail to one another, and raise funds for community organizations along the trails where we race. Every day, it’s a gift to be part of the community that’s formed around the team.

It’s given us a chance to share mushing, this mysterious lifestyle, with people who might not otherwise encounter it. We spend a lot of time answering questions: Why do the dogs look like that? What do they eat? Do they get cold? What happens when they retire? And sometimes those questions (which we’ve also addressed in this book) lead us to new questions, ones I’m still trying to figure out. What does it do to your heart to work so closely with animals? How does it change your relationship to nature, to life on earth?

I don’t want to live like weasels; I have too many necessities. But I do want to live like sled dogs.

My goal has always been to share mushing as it is, not just the beauty and wagging tails but the hard parts, too. The sport has challenges that are, in their way, romantic: storms and wolves, the bone-deep chill that comes with sleeping out in forty below. Even sleep deprivation and hallucinations can be points of pride.

But mushing also means facing difficulties that are banal, uncomfortable, and sometimes sad. On a run in 2018, while crossing Devil Track Lake in Minnesota, one of our dogs attacked and almost killed another dog, Boudica. I couldn’t break up the fight. Finally, terrified, I threw myself over Boudica and shielded her with my body. As horrible as it was, it felt important to share that story, too. I didn’t want to paint a facade over a real and complicated lifestyle; I wanted, have always wanted, to share reality. In part, this felt like a responsibility. If someone decided to start mushing after hearing my stories, it was only fair to them—and more important, to their dogs—to give a clear idea of what they were committing to.

The truth is that mushing is both very exotic and not exotic at all. If you’ve ever had a dog pull you on a bicycle, or while you run, that’s a kind of mushing. And if you’ve ever thrown a tennis ball for a retriever, again and again, then you have an idea of the bottomless enthusiasm that a sled dog brings to the trail.

Sled dogs aren’t half-wild, as some suppose. They’re dogs, with all the courage and sensitivity of dogs, the curiosity and excitement and longing to be loved. They’re also unique, both physically and mentally; they’re adapted to cold, have an unceasing drive to run, and have the rare athleticism to see that through. They can be very happy living as pets, as long as their significant exercise needs are met; they can be very happy living outdoors with their team; and many of them, even most, will enjoy both of these lifestyles over the years. If anything, they’ve taught me to be half-wild: to build a life outdoors, following instincts, trusting my teammates. They’ve taught me that wilderness isn’t a place to visit, but a home to return to. They’ve taught me that there is far less difference between humans and animals than I thought.

One of the first essays I ever loved was Annie Dillard’s “Living Like Weasels.” She describes a weasel’s skull latched to an eagle, still biting, long after the weasel itself died and the rest of its body fell away. And she writes:

I think it would be well, and proper, and obedient, and pure, to grasp your one necessity and not let it go, to dangle from it limp wherever it takes you. Then even death, where you’re going no matter how you live, cannot you part . . .

I don’t want to live like weasels; I have too many necessities. But I do want to live like sled dogs. I want to travel through life with a team that has my back.

I want to explore new places, but get just as excited about familiar ones. I want to find comfort in routine and opportunity in change.

What does it mean to live like sled dogs—for the dogs, for me, maybe even for you?

_______________________________________

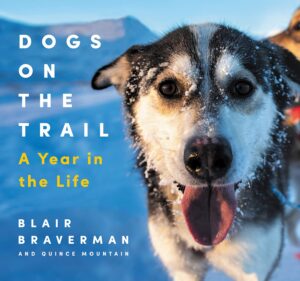

From Dogs on the Trail by Blair Braverman and Quince Mountain. Copyright © 2021 Fact That Supports This, LLC. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Blair Braverman

Blair Braverman is a writer, dogsledder, and adventurer who uses innovative storytelling to make the outdoors accessible. She is the author of Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube, a contributing editor to Outside magazine, and a contributor to The New York Times, Vogue, This American Life, and elsewhere. She lives in the northwoods with her husband, Quince Mountain, and their team of sled dogs.