On Zombie Ants, Parasitic Fungus, and the Violent Legacy of Anti-Blackness

Maria Pinto Considers the Striking Parallels Between the Human and the Natural Worlds

“To be a person is to be worried that you might not be one.”

–Timothy Morton, Dark Ecology

*Article continues after advertisement“Coherence is when the parts of an object weirdly overlap so that they become the “same” thing…”

–Timothy Morton, Dark Ecology

*

The ant lists this way and that, like she’s cross-faded. She has never been this off task. Anytime she tries to ascend into the canopy where her life has been spent, in galleries carved through the dead branches of the tree in service of her queen, she convulses, staggers, and falls to the ground, where she’s pulled from one queendom to another. Where her volition was—or where the things that might be considered her volition would be if she was truly individual, rather than a cell in a superorganism—there is now Ophiocordyceps unilateralis. It works through her, straining her corpse toward an undreamt-of goal. Is there anything more lonely than this, a eusocial being in her moment of mortal digression away from the body of the colony? Anything more supremely wrong? She is a zombie.

This is the technical term. This is how the biologists refer to her, because “parasitized ant” doesn’t contain the cross-species body horror an onlooker is sure to feel when, at solar noon, the parasite makes the ant clamp violently down on a vein on the underside of a low-slung leaf and stay clamped there, until well after her eyes have gone dim. She looks like herself, but she is mycelium made ambulatory, until such a time as her body more directly expresses its new genetic aims by becoming a fungal sculpture, bursting cottony at the seams. And what a sculpture it will be: a little too much, self-consciously macabre, a bit emo, to be honest. How like her brain on a stake the perithecia looks, as if speared by this new horn on her head. With such ornamentation, the shell of her frozen in a stance she would never have taken in life, she is a former ant, teeming with her own death.

The zombie is a spiritual vessel for unspeakable anguish. A repository of hopelessness. No peace even in death.

In college, while dissociating weekly, I took literature and history classes with names like “Creating the Transnational Caribbean” and “New World Revolutions.” During these blocks, my life, which had been afloat in time before, was given historical anchors and context, and I gained perspective that would have been impossible without that academic remove. My mother, I learned, was part of a wave of immigration from Jamaica that was now legible to some as a decades-long “brain drain” (terrible term), imperialism that obligates its subject to move away from home. I read about Haiti and understood why the nation, far more than a simple repository of our childhood anti-Blackness and received self-loathing, was a renegade, a global actor whose attempts at self-determination would be punished throughout its existence; that the people of Haiti would be right to burn the rest of the world to the ground. My mother, our family, Haiti, my self—as Caribbeans we all existed and exist at several hostile intersections, making maneuverability difficult. Difficult but not impossible. It is no wonder then that the zombie, the restless embodied dead, more potent than, more confrontational than, a mere wispy ghost, would be born in this place.

Zombies come from seventeenth-century Saint-Domingue, the French colony that would become Haiti and the Dominican Republic. In this iteration, zombi refers to the bodies of those not allowed to pass over to lan guinée, literally Guinea or West Africa, that lush green home, paradise. A zombified body can be animated with a will not its own, to pay off a debt. Out of the brutal atmosphere in which an enslaved plantation worker led their life sprang the creature who, even after having died, perhaps by their own hand, must still toil endlessly, the balm of rest an impossibility. In this context, the zombie is a spiritual vessel for unspeakable anguish. A repository of hopelessness. No peace even in death.

Later, after the revolution, what it means to be a zombie will shift—zombification will be the result of a voodoo practitioner entrapping the soul of the recently dead, giving the corpse a whiff of that soul, then pressing the resulting creature into service. This manipulation of the boundary between life and death, which we in the West take as the ultimate truth and an important site of Cartesian rationality, is one reason that the Haitian zombie is such a potent figure. If the world seems to have fixed us in our helplessness, but death is not a fixed state, then what else is possible, after?

*

Armed with a jeweler’s loupe I venture into my home woods and look for Gibellula-like fungi, the ones that transform spiders from cunning stop-motion tricksters to hollow, fleece-sweatered cadavers. The uniformity of the resultant arthropod final resting places suggests these fungi may affect the spider’s behavior just like O. unilateralis does that of the ant: that is, piloting them to the perfect environment for the fungus to thrive. I have found these small but spectacular mycelial fireworks stitched to the bark of trees several times. It does not get old. After my most recent discovery of one such ascocarp on a chilly November day, I apologized to the tree that held it and the fungus who might not have finished sporulating and peeled the bark to bring Gibellula (or similar) home for closer study. The minute fuzz reminded me of a mycoacquaintance and biotechnologist who once documented his use of Beauveria to infect house flies at his place. Pest control for nerds.

Having oohed and aahed through my macro lens over the many tiny lavender clubs extending from the yellowed abdomen, and thinking of Anansi, I went to the biodiversity cataloguing app iNaturalist. I wanted to look at the program’s map and see which cordycipitoid species were being recorded from the Caribbean. Noting the few Ophiocordyceps observations in Jamaica, I shifted my attention to Haiti. The only entomopathogen that has been recorded on the app from that side of the landmass is Moelleriella epiphylla, a scale insect parasite. Anansi, who goes by the name of Ti Malice in Ayiti, laughs as I pin my former spider to a board and mount the cadaver under glass.

In 1937, Zora Neale Hurston went to Haiti and Jamaica on a Guggenheim fellowship to study spirituality and magic. In Tell My Horse, her book about the trip, Hurston writes, “What is the whole truth and nothing else but the truth about Zombies? I do not know, but I know that I saw the broken remnant, relic, or refuse of Felicia Felix-Mentor in a hospital yard.” To accompany these words, we get a haunting black and white photograph of that “remnant, relic, or refuse”—a thin figure in an amorphous dress with an illegible face and lightless eyes, arms flung back as if she’s shambling towards the photographer. The space between these two sentences of Hurston’s is expansive; it contains countless possible worlds. Felicia died in 1907 and was buried. In 1936, the “remnant, relic, or refuse” turned up naked on a farm, insisting that she used to live there. Hurston reports that Felicia’s remnant is an outlier because, in general, recovered zombies had lost the power of speech. Felicia’s brother recognized her body, and it was sent, still animate, to the hospital.

The twenty-nine years between her funeral and her hospitalization haunt me. Where did she go? What was she made of?

Hurston learned that the houngan, either hired to seek revenge or working for himself, knew there was an important step that could not be skipped lest the zombi’s enslavement prove incomplete: “First, he is carried past the house where he lived. This is always done. Must be. If the victim were not taken past his former house, later on he would recognize it and return. But once he is taken past, it is gone from his consciousness forever.” Whoever turned Felicia into a zombie may have skipped this step.

Zombie ants do not go home.

There are astonishments that hold you still and whisper-shout that earth is also like this—that remind you every inexplicable process taking place inside an instant on our planet laughs darkly at our ennui, our nihilism, our death drive. My latest astonishment is Ophiocordyceps’s complex and audacious behavior. Even if science is explaining the biochemical and mechanical processes behind O. u.’s puppeteering, still: The sheer intimacy of parasite and host? What that clumsy waltz has taught and untaught me about evolution?—that smacks of the kind of secret we will dwell in all our lives.

Here is a brainless being without a nervous system (that machinery we call a requirement for intelligence) that has so completely commandeered a “more elaborate” being’s body that that body can be considered part of the fungus’s “extended phenotype”—that is, effectively a continuation of the fungus’s own genetics. And, researchers suggest, it may be the ant’s circadian rhythms (its sense of timing, a comedian’s greatest tool) that are “hijacked” by Ophiocordyceps to allow this feat. When does she cease to be an ant and become mycelium with legs? The minute her former neighbor releases the spore that will connect with her? When the spore gets in? When she performs the first act that cannot be read as ant instinct? When she stops living on her time and starts living on the parasite’s?

The infected ant is the real-life zombie in an instructive inversion—the borrowed word once again gets unstuck from culture, unstuck in time.

Many respond to this dance between insect and fungus with empathy for the former and disgust and fear of the latter. Natural enough, of course. Like ants, we’ve got a brain and a nervous system, which have pride of place in the Western study of biology. But this focus has made us ignore the vitality and volitions that make up each individual “us,” and which may have more impact on who we are than we ever dreamed possible. Slowly, slowly, we internalize that the appendix is not merely vestigial but may be an important repository for gut bacteria, which are important for gut health, which is important for brain health. The insect pathogens have held a mirror up to my body and asked me to look beyond what my naked eye can see, to the rest of my ecology.

The mini-documentaries that describe entomopathogens do so with a flair for the dramatic—as soon as the word “spore” is uttered, dissonant music starts up in the background or replaces the soundtrack of soothing rainforest sounds to let you know the dread villain has arrived to plague the individual hero. The parasite is no good for that “individual” ant, of course (which is of course no way to think about the Camponotus species in question because they are eusocial), but is it good for Amazonian ecology to keep carpenter ant populations in check? And is what’s good for Amazonian ecology good for Camponotus genetics on a whole?

Maybe it’s because I learned about cordycipitoid fungi through a mycophilic lens, but “summit illness” and “infection” have always seemed insufficient to describe the phenomena, even though Ophiocordyceps is a parasite, its expression a form of insect pathology that is no good for the ant. Maybe the keyword is balance? Bacteria become disease when balance is absent. We should sing out “My name is Legion, for we are many,” but sometimes one voice drowns out the rest. We are chimeras who are loath to admit it. Multiplicity’s the ultimate preexisting condition.

This parasite, this process, raises more questions than it answers, but at my back I hear time’s gas-guzzling chariot and still O. unilateralis asks me one more question: What have the many organisms that amount to you done lately to know they—to know you—are free? O. unilateralis wants to know how I would know whether my movements were my own or not.

Kyle Bishop, an associate professor of English, seeks to put the zombie ant in historical context by reckoning with the zombie’s Haitian roots. He also asks what we can learn from the “real-life zombie”—that is, the ant. “To me what the zombie is, is the loss of agency,” says Bishop. “Ultimately it’s a slave metaphor. Nothing is more terrifying than losing your ability to control your own body or make your own decisions.”

If zombies were only a metaphor for the terror of losing your autonomy, then we’d be awash in them. Losing your ability to control your own body and make your own decisions is the daily lived reality of prisoners, Black people, those who can reproduce, trans people, the colonized, the disabled, the elderly, children, and the global poor, to name a few. If a zombie is a mere metaphor, then what of Felicia Felix-Mentor’s twenty-nine years? Who is defining real life here? What world is he looking at as he makes that definitional decision? The author suggests that the infected ant is the real-life zombie in an instructive inversion—the borrowed word once again gets unstuck from culture, unstuck in time. We are the metaphors for them.

One student of Ophiocordyceps unilateralis used a fascinating word to describe the parasites’ manipulation of hosts. According to biologist David Hughes, roughly 50 percent of earth’s biomass is parasitic, yet only a tiny minority of those parasites manipulate behavior, because the adaptation is “extremely expensive biologically. Most parasites can do a really good job [of transmitting their genes from one host to another without having to control behavior.” So what makes them do it? Why have they evolved to be so danged ruthless, so danged spectacular? The simple answer is that the ants with which they coevolved would not tolerate the scent or drunken behavior of an O. unilateralis-infected ant among their ranks, even if the ant had been able to find their way home. Without the reverse-homing effect of the fungus’s will as expressed by the ant’s movement, O. unilateralis would not have an opportunity to form its fruiting body and to sporulate—the uninfected ants would tear the zombified ant limb from limb or toss them in rubbish receptacles as soon as they got wind. So the evolutionary best bet for the fungus, it turned out, was to isolate, isolate, and isolate again, till such a time as the spores could fly free. Zombie ants do not go home.

When an enslaved African took their own life on a French plantation in Saint-Domingue, it cost the person who called himself her owner a pretty penny. For this reason, overseers threatened their charges with the zombification of their corpses and continued labor. Suicide has been expensive since capitalism existed; what’s the cost of an entangled life?

__________________________________

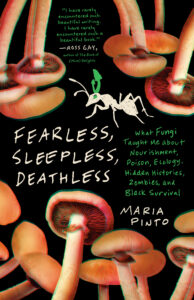

From Fearless, Sleepless, Deathless: What Fungi Taught Me about Nourishment, Poison, Ecology, Hidden Histories, Zombies, and Black Survival by Maria Pinto. Copyright © 2025 by Maria Pinto. Published by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher.

Maria Pinto

Maria Pinto is a Boston-area writer, mycophile, and educator who was born in Jamaica and grew up in South Florida.