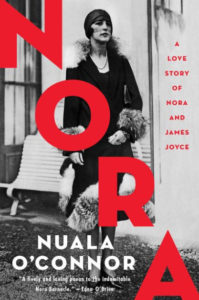

On Writing Nora Joyce into Biographical Fiction

Nuala O’Connor Considers the Interior Life of a Literary Icon

Twenty-five years ago I moved from Dublin to Galway city on the western seaboard, where Nora Barnacle, wife of James Joyce, was born and raised. I was aware of Nora as a strong, vibrant local woman, one who gave Joyce her unquestioning love and support. As a teenager, I had read and loved Brenda Maddox’s biography Nora—the Real Life of Molly Bloom, and I often thought about this feisty Galway woman who became a true European and amusing muse to Joyce. I admired the way she had escaped oppressive, Catholic Ireland and found freedoms abroad. I began to attend the annual Bloomsday celebration at Nora’s mother’s house in Bowling Green—now a tiny museum—to celebrate both Nora and Joyce, and I was one of one hundred readers who read there, from Ulysses, on the centenary of Bloomsday, in 2004.

It occurred to me to write a novel about Nora when I was studying Italian by night and wrote an essay about Joyce’s friendship with the Triestine writer Italo Svevo. Nora, I found, intrigued me more than either of the men. What was her life really like, I wondered? Around the same time, we rescued a spirited, one-eyed cat and named her Nora Barnacle, and I wrote a short story about Nora, “Gooseen,” which won a prize and was well received. But I found I didn’t want to let Nora go—it became crucial to me to unpick, in a novel, the whys and wherefores of her life with Joyce and after him.

I wrote NORA not just out of curiosity, but also out of love. Biographical fiction, for me, is a way to honor women who’ve been smudged by history, downgraded as The Wife, as if as prop to some notorious man, a woman was not personally important and essential to her lover’s success. I aim to resurrect these women—the Noras, Emily Dickinsons, Belle Biltons et al—and re-introduce them to the world as the rounded, wonderful, spiky people that they were. I don’t want to make paragons of them, but I aim to get a feel for what their lived lives were like.

When I began my novel earnest, I was determined not to turn Nora into an Edwardian, or 1920s, caricature. Nora, who had a very distinctive and strong character, would be resolutely herself in my story, she would remain to the fore, letting us into the day-to-day world she occupied alongside her beloved Jim. She wouldn’t be background blur to James Joyce’s genius; Nora was not, anyway, a literary wife in the way we understand that phenomenon—she had her own non-literary concerns and tastes, and I wanted my bio-fictional portrait of her to reflect that.

NORA is narrated in Nora’s voice and it explores her personal issues, many of which have to do with Joyce and their children, naturally, but she also has to contend with a backward look to Ireland and how that fits with being European. Nora was a straightforward, bawdy, kind person and, interestingly, for a woman who lived out of wedlock with her man, she could also be a little strait-laced and proper, a hangover perhaps from the morality of her Catholic upbringing. NORA spans the Edwardian era, the civil war in Ireland, two world wars, and ends with Nora’s death in 1951. The novel’s events take place in Ireland, Austria, Italy, France, Switzerland and England. Nora may have lived in a Europe in flux but, at heart she was an Irish Catholic, though one with modern sensibilities; the outward respectability she liked to uphold concealed the true maverick that she was.

Nora, I found, intrigued me more than either of the men. What was her life really like, I wondered?

Galway-born Nora met James Joyce in his native Dublin, where she had come to work in Finn’s Hotel. She was twenty years old when Joyce approached her in the city centre, in June 1904. Nora’s biographer, the late Brenda Maddox writes: “Love at first sight is grossly underestimated: a single glance can take the whole person.” Joyce, to Nora, might have been a Swedish sailor in his nautical cap and shabby plimsolls, but he was attractive and serious-looking, and had arresting pale blue eyes; Nora, ever-stylish, was probably drawn to Joyce’s eccentric looks.

For herself, Nora had an erect, fearless saunter, masses of auburn hair and dark blue eyes, and her lovely name surely pleased Joyce, a committed fan of Ibsen and his Nora. They were each “taken” it seems by their first glimpse of each other, both confident, both sure of their own worth. Joyce was an idle university graduate, Nora worked in Finn’s Hotel. Neither of them was used to money: Joyce’s family, large and Catholic, were the fallen genteel; Nora’s were the Catholic working class—she had been raised by her grandmother. Both were urban children of port towns, both had an inner restlessness, a need to be elsewhere. This apparently unsuited pair had as much in common as they did not.

Nora, unlike Joyce and unlike her own siblings, was brought up as an only child. No doubt she was minded well as a girl, no doubt she listened in on granny’s adult conversations. Whatever the truth of it, Nora became an oral storyteller with a gift for language, and for saying straight out what she perceived to be true. Nowadays, we might say she had no filter. And Joyce was charmed by Nora’s west of Ireland turns of phrase, by her warm, earthy charisma, and good humor, and he used her stories and phrases liberally in his work. Nora, in turn, was taken with Joyce’s sensitivity, his book-learning, and his sincerity. Both of them were ripe for novelty when they met: Joyce was tired of holy Ireland, of his mercurial, drunken father, and of his needy siblings. He had recently tasted Paris and liked it. He was up-ended, too, by the death of his mother and grief may have precipitated his restlessness, his desire to start anew in a less religion-basted society.

Nora, that June, was probably lonely for her Galway tribe, still trying to find a proper niche in Dublin. The pair found each other when both were ready for the possibilities and promise of love and, it turned out, they were a good match. Joyce, self-possessed and unsettled, found a steady yet spontaneous companion in Nora, one happy to set out into the unknown by his side.

After a four-month courtship, Joyce would not marry Nora before they absconded to Switzerland, and she knew if Jim abandoned her, she would be destitute and shamed. They eventually married twenty-seven years into their union but, until then, they lived a non-traditional yet semi-conventional life in Europe—unmarried and poor, with a young family, posing as a married couple: James wrote and worked as a teacher, Nora kept house and minded their children, Giorgio and Lucia. And Joyce continued teaching until wealthy benefactors and book royalties meant he didn’t have to anymore.

For herself, Nora had an erect, fearless saunter, masses of auburn hair and dark blue eyes, and her lovely name surely pleased Joyce, a committed fan of Ibsen and his Nora.

The Joyces cared about appearances, and only partially fitted in with the ex-pat, bohemian set they were a part of, particularly in Paris. There they socialized and, sometimes worked, with Beckett, Hemingway, Ezra Pound, Djuna Barnes, Sylvia Beach and the Guggenheims. Joyce, convivial when drinking, and a genius besides, was welcomed; Nora, though warm and hospitable, was a bit of a conundrum among that group. Some didn’t understand why the great writer was married to a non-literary, straightforward woman. Unlike, say, Vera Nabokov, Nora wasn’t her husband’s editor as well as partner, lover and minder. Nora had no ambitions to be literary and those who really came to know her understood her worth: she was Joyce’s shield and his prop, his comfort and his caretaker—he did not function well without his “little wild-flower of the hedges” by his side.

Nora was fully herself by the time she met Joyce and he loved the enigma of her as much as the charming stories of her girlhood that she fed him, and he used, in works such as “The Dead” and to fashion Molly Bloom in Ulysses. Joyce saw Nora as the phenomenal individual she was and thoroughly admired her unwavering inner strength and optimism; he appreciated the durability she possessed that he did not and she was, to him, superior in many ways. He told his brother Stannie that Nora’s disposition was nobler than his own, saying too that he didn’t just love her, he admired and trusted her. It wasn’t all even-keeled, of course, Nora asked the devil to take Jim when he was “off on one of his rampages”; she knew the damage alcohol did to his health, his weak eyes in particular, but Joyce loved to drink and was at his most gregarious when he did—it’s likely he needed to be intoxicated to socialize comfortably.

Nora sometimes privately complained about the artificiality of the lives of the great dilettantes in free-spirited 1920s Paris. Her Jim may have been the most famous writer in the world—once Ulysses was published in 1922—but to Nora, he was simple-minded Jim, her errant but adoring partner. She was in love with Jim the man, not Jim the writer, but she supported his devotion to his art and was proud of his success, and glad of the material security it brought. Nora honored his writing by facilitating him to get on with it, and by being mindful of his fragile health, but it was the everyday parts of him that she revered and took care of: his needs as lover, as diner, as father, as companion, as man with failing eyesight.

NORA the novel, then, is an homage to Nora as individual, woman, caretaker and mother, firstly, and, secondly, to Joyce as life-partner, father, and genius writer. I try to look with empathy at two fresh young people leaving their island, not knowing what lies ahead. A couple who age and grow together, while negotiating the travails of life that so many of us deal with—finding a home, relationship woes, raising a family, caring for a child with health issues, various griefs, career lows and highs. Those people may be the great James Joyce and the inimitable Nora Barnacle but, in 1904, they were just two young people, setting out together to who knew what, who knew where. NORA, I hope, opens out the intimate, intriguing detail of the strange and lovely journey they took side by side.

__________________________________

From NORA: A Love Story of Nora and James Joyce by Nuala O’Connor. Used with the permission of Harper Perennial. Copyright © 2020 by Nuala O’Connor.

Nuala O'Connor

Nuala O’Connor new book is Becoming Belle. She is also the author of Miss Emily and writes in her native Ireland under the name Nuala Ní Chonchúir. She has won many fiction awards, including RTÉ radio’s Francis MacManus Award, the Cúirt New Writing Prize, the Jane Geske Award, the inaugural Jonathan Swift Award, the Cecil Day Lewis Award, and the Kerry Irish Novel of the Year Award, among others. She has been published in Granta, The Stinging Fly, and Guernica, among many others. She was born in Dublin in 1970 and lives in East Galway with her husband and three children.