On Wartime Life in Occupied Donbas, c. 2015

Stanislav Aseyev Reports From Donetsk

Editor’s note: The following is a report dated February 4, 2015 and originally published in In Isolation: Dispatches from Occupied Donbas. It describes life in Donetsk, located in a contested region of eastern Ukraine occupied by separatist forces that support the Donetsk People’s Republic (referred to, here, as the DPR).

*

In this sketch, I want to share with you more than the situation that has developed at the separatist checkpoints set up all over Donetsk, more than the little life that each checkpoint has, with its own laws and order. I want to tell you the story of a man whose fate shows that the war in the Donbas is far from a black-and-white affair, and is instead more of a kaleidoscope with a huge number of colored bits.

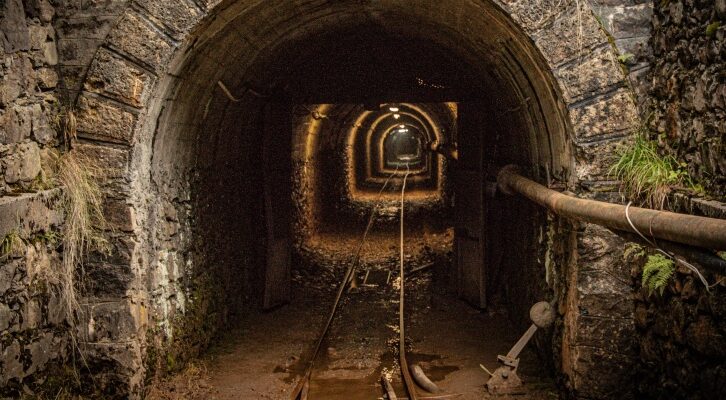

The fortified structures that the militants began to put up around our area back in the beginning of spring last year were and continue to be the main symbol of the separatist movement. It is precisely in these posts that the fighters for “a free Donbas” began their campaign, armed with no more than bats and rocks.

Set up on all the city’s key intersections and main roads, the checkpoints have brought together individuals whose life interests are far outside the scope of any ideological goals. Most of the checkpoints are now controlled by fighters from the Vostok and Mech battalions, with a smattering of members of Oplot—none of whom have distinguished themselves by any special sense of duty or idealism in this war. Indeed, among local militants, the word “checkpoint” brings up only ironic smirks: as a rule, no military operations take place within city limits of Donetsk or Makiїvka and, with rare exceptions, any threat could only be posed by “saboteurs or diversionary groups” (a World-War-II-era Soviet phrase) of the Ukrainian armed forces.

This means that standing at a checkpoint is a profitable and relatively safe activity, offering opportunities, on one hand, to be paid officially by the Donetsk People’s Republic’s “defense ministry,” and, on the other, to collect “donations” from those who happen to drive past in expensive foreign cars. This tradition started back in the day when the militias fought for no pay whatsoever and really had to beg from the cars they stopped.

[Separatist] units are filled with people with drastically different backgrounds, often with no ideological stake whatsoever in this war.From the time around the end of August to early September 2014, these spots were rightly called bazaars: by then, in addition to money, the militants were collecting literally everything that could possibly be of use to them during their arduous days at the intersections. This could include fresh meat, smoked poultry, bottles of wine or kvas, or medical supplies, which might be demanded directly or in the form of money, with the phrase “Donate for my arm,” and a militant’s bandaged limb thrust through the open window of the car. In short, the demand for “donations” might be satisfied by anything found in a car traveling on the intercity highway.

Needless to say, at those places—the checkpoints—a pecking order had been established as to who had the right to levy “duties” on drivers, along with a table of rates for this kind of business, providing an income for those practicing the trade and their families. At this point, the checkpoints only stop passenger cars and trucks, letting marshrutky, the fixed-route minibuses, go by without bothering them at all.

Let me share a story of the kind of man you might have seen standing at one of these “bazaars” just a few months ago, with a machine gun in his hands and a karakul lamb skin hat on his head. This is the type of man you probably would have decided on the spot was the enemy, yet his threatening outward appearance and social attributes would have obscured his story.

This man belongs to those who, from the very start, were skeptical about the DPR and the idea of “Novorossiia.” At a time when most of our mutual acquaintances were already standing at the crossroads or making their way in tanks to the Donetsk airport, he continued to work in a coal mine, where he held a rather prominent position.

Then one day came the shift where they were barely able to pull him out from underground because a battery was shelling them. The next day the coal mine closed down and operations stopped. He was left penniless, of course, and was unable to get a job even as a loader, because there were simply no jobs in our region. After a week of heavy drinking, he found himself one morning lying handcuffed on a wooden pallet at the Makiїvka train station. Not far from him stood a few militants in camouflage and some guy who was already digging a trench.

My friend was politely told that, as a useless alcoholic and drug addict, he had been arrested by the Makiїvka commandant and brought there the previous evening. Now he was going to spend two days digging trenches together with other “social trash” like himself—that is, the man with the shovel. Not happy with this interpretation of things, Artem—for that was his name—announced that he didn’t plan on shoveling anything and demanded that they remove the handcuffs and release him.

The militants actually removed the handcuffs—after which they beat him up for the first time, to such a degree that, as he described it, he lay unconscious on that pallet for half a day before slowly coming to. Not a man of great endurance, my friend nevertheless once again declared that it was easy enough for any five guys to beat him up and mumbled something about a fair fight. At this, the men beat him brutally a second time, using their rifle butts and tossing the shovel in for good measure, and said that if he refused to dig, the other guy who had been shoveling all day alone because of him would bury him alive.

He was forced to join the DPR simply in order not to starve to death.In the end, Artem managed to dig part of the trench by evening, then spent a chilly night on the bare pallet. The next day, not having a single coin in his wallet, covered in blood and dirt, he walked from one end of the city to the other. After this, he had to drink bouillon through a special straw for two weeks.

As you can understand from this story, this incident did not especially increase the man’s sympathy for the DPR and as of today he has moved to one of the oblasts in the middle of Ukraine. However, he managed to collect money for this trip by working at the Makiїvka checkpoint when, after healing up and wandering around the coal mines that were still working looking for a position, he was forced to join the DPR simply in order not to starve to death.

When I met Artem in the Vostok battalion and asked what he thought now about the war and the DPR, he admitted with a smirk that he was only alive thanks to the war and had no idea how he would otherwise find the means to survive right now.

It’s clear that, nominally, he could be considered an “enemy of Ukraine,” since working as a checkpoint militant was not the only option available in the circumstances that he found himself in, as one might castigate him.

A lot of time could be spent arguing over this. But the very fact that the DPR and all its army units are filled with people with drastically different backgrounds, often with no ideological stake whatsoever in this war, becomes that stumbling block against which many a foot will trip in the attempt to clearly divide those people into “us” and “them.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from In Isolation: Dispatches from Occupied Donbas by Stanislav Aseyev, translated by Lidia Wolanskyj and published by the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute.