On W.E.B. Du Bois and the Disgraceful Treatment of Gold Star Mothers

Chad L. Williams Considers the Symbolic Battles of World War I

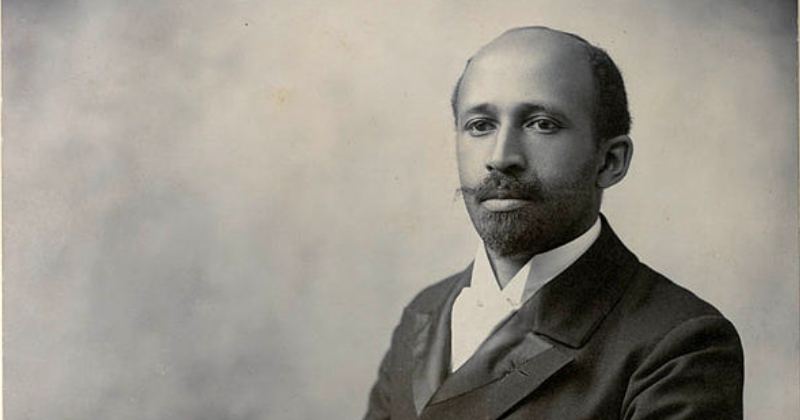

Along with the question of war guilt, another controversy in the spring and summer of 1930 offered W.E.B. Du Bois a reminder of the First World War’s bitter legacy. In early 1929, after years of pressure from such groups as the American War Mothers, the American Gold Star Mothers, and the American Legion, Congress passed a pilgrimage bill authorizing the War Department to sponsor trips to France for mothers and widows who had lost their sons and husbands in the war, so that they could visit their loved ones’ final resting places.

Although the law made no mention of race, when it came time to organize the sojourns, the War Department issued a memo stating that Black mothers and widows would travel in separate groups, reasoning that the women of both races would naturally prefer to mourn in the company of their own kind. Word of the War Department’s plan became public in March 1930, just before the first ships were set to sail.

The NAACP and much of the Black press cried foul. “Black mothers and widows saw their sons sent to Jim Crow military camps and into Jim Crow units during the hectic days of 1917 and 1918,” The Chicago Defender reminded its readers. “They saw them go away willingly, secure in the belief that their sacrifices would mean something to those who remained at home. Then, these mothers saw Jim Crow units return to this country one after another, and finally awoke to the realization that their sons would return no more.” The NAACP promptly fired off letters of protest to President Hoover and members of Congress, demanding that the War Department reconsider.

Du Bois did not participate in the public pressure campaign, but made his views clear in private correspondence. William King, a member of the Illinois State Legislature, considered introducing a measure to protest the War Department’s actions and sought out Du Bois’s opinion. Du Bois offered a sharp response. “The segregation based mainly and specifically on race and color which the United States Government carries on is despicable, illogical and uncivilized … To perpetuate it in the case of the Gold Star mothers who are visiting great cemeteries where the putrid remains of their dead sons were buried very largely by Negro soldiers, is the last word in this national disgrace.”

African American women did not have much of a place in The Black Man and the Wounded World.

After the War Department held firm to its Jim Crow plans despite pledging that “each group will receive equal accommodations, care and consideration,” the NAACP and the Black press urged a complete boycott of the program.38 “No black with self-respect will go if she has to go on that segregated ship,” the Defender scolded. “Their boys would want them to do this. Mothers, don’t shame those boys further by going to visit their graves on Jim Crow ships!”

The overwhelming majority of the Black Gold Star mothers, however, did not heed this advice. The first ship, a retrofitted freight liner carrying 54 grieving women, departed New York on July 12, 1930. They were accompanied by Colonel Benjamin O. Davis, at the time the highest-ranking Black officer in the military, who was fluent in French.

He volunteered to protect their dignity and ensure that they received every available courtesy. Over the next three years, 279 Black women made the trip across the Atlantic to visit their deceased sons and husbands, voicing no complaints about their treatment and expressing gratitude to the government for giving them a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Du Bois’s inability, along with that of other Black male leaders, to see the Gold Star Mothers as anything more than racial symbols reflected his view of the war and of the history he was writing. As the title itself revealed, African American women did not have much of a place in The Black Man and the Wounded World. In the hundreds of pages he’d drafted over the years, Du Bois made no mention of the home-front contributions of Emily Bigelow Hapgood, Mary Church Terrell, Susan Frazier, Mary Talbert, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, and other Black women activists.

In chapter 18 of his manuscript, “The War Within the War,” he did decide to “lump together” an assortment of topics “all quite different and yet all shot through with this one peculiar color problem.” This included a brief examination of the work of Black women during the war, based mostly on Addie Hunton and Kathryn Johnson’s Two Colored Women with the American Expeditionary Forces and a small booklet issued by the Colored Work Committee of the YWCA.43 Not surprisingly, he focused almost exclusively on the discrimination they faced.

While Du Bois could laud the labor and sacrifice of Black women, he believed that the history of the war, like that of the race more broadly, was ultimately the history of Black men.

__________________________________

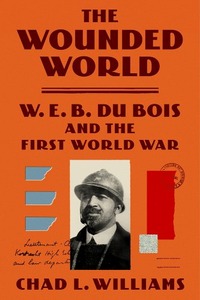

Excerpted from The Wounded World: W. E. B. Du Bois and the First World War by Chad L. Williams. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, April 2023. Copyright © 2023 by Chad L. Williams. All rights reserved.

Chad L. Williams

Chad L. Williams is the Samuel J. and Augusta Spector Professor of History and African and African American Studies at Brandeis University. He is the author of the award-winning book Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era, the coeditor of Charleston Syllabus: Readings on Race, Racism, and Racial Violence, and the author of The Wounded World. His writings and op-eds have appeared in The Atlantic, The Washington Post, Time, and The Conversation. He lives in Needham, Massachusetts.