On Turn-of-the-Century Suffrage Cookbooks, Trojan Horse For Women's Equality

In Which One Might Learn How to Make "Pie for a Suffragist’s Doubting Husband."

Collectively, the suffrage cookbooks were much like the movement that spawned them. Suffrage was a big tent, covering those who shared a common vision about voting rights for women, but for whom just about everything else was up for grabs. Likewise, the suffrage cookbooks had a common aim—to support suffrage—but that was about all.

While they were all part of a savvy campaign to win over skeptics and even opponents, to rally those already on the suffrage bandwagon, as well as to fundraise for the cause, in 21st-century parlance their messaging was all over the map. Even within a single cookbook, one can often sense that this was no orderly march.

Only a handful of suffrage cookbooks survive. Published by various organizations within or supportive of the suffrage movement, there are eight if you count two pamphlets, six if you do not. Any others are lost to us. It is always possible that a copy of another one exists, cast aside in an attic somewhere or languishing in an as-yet uncatalogued box of memorabilia donated to a state historical society or other repository.

There are tantalizing hints of at least two other suffrage cookbooks (one created in Nebraska around 1906 and the other in New York in 1917) in suffrage publications and the records of various suffrage organization meetings, but neither has surfaced to date.

The existing cookbooks all came out of the mainstream suffrage movement, which makes sense as they reflect the desire to show that a woman with domestic skills and an interest in home and hearth could also be a suffragist, devoted to gaining the right to vote.

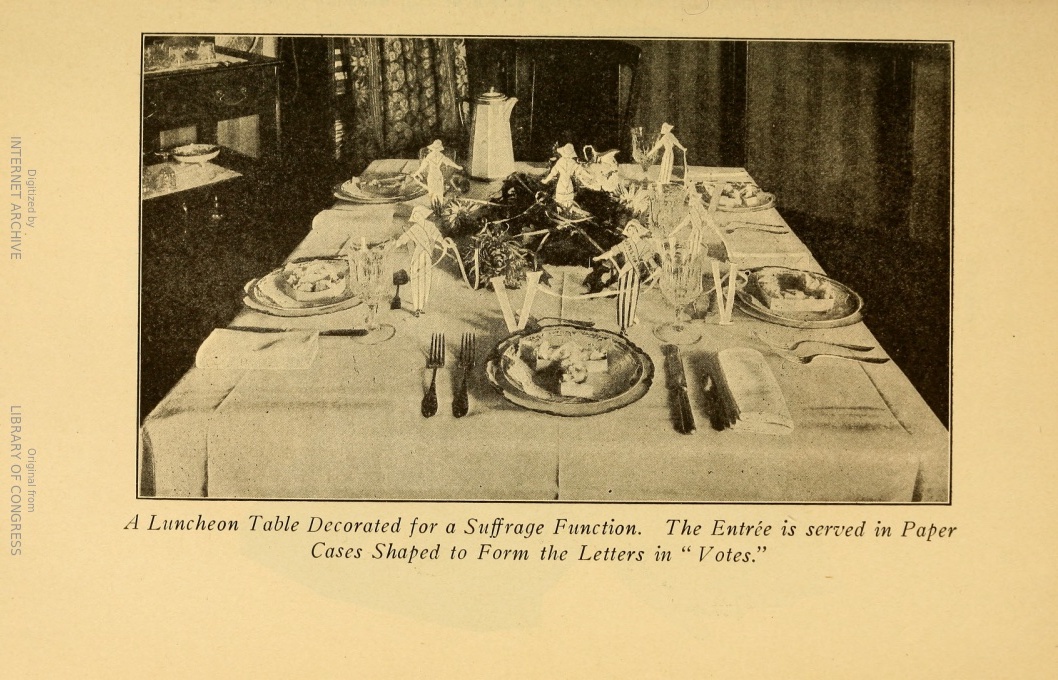

The cookbooks themselves sometimes reinforced that image of suffragists as nonthreatening, domestic goddesses.

The first known suffrage cookbook was published in 1886, almost 40 years after the Seneca Falls Convention, and the last two came out in 1916, four years before the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. In order of publication, these books are:

1886: The Woman Suffrage Cookbook, Containing Thoroughly Tested and Reliable Recipes for Cooking, Directions for the Care or the Sick, and Practical Suggestions, Contributed Especially for this Work, Burr (Boston, Massachusetts)

1891: The Holiday Gift Cookbook, the Equal Suffrage Association of Rockford, Illinois

1909: Washington Women’s Cook Book, Jennings (Seattle, Washington)

1913: For Better Baking, The Political Equality Club of Rochester (Rochester, New York)

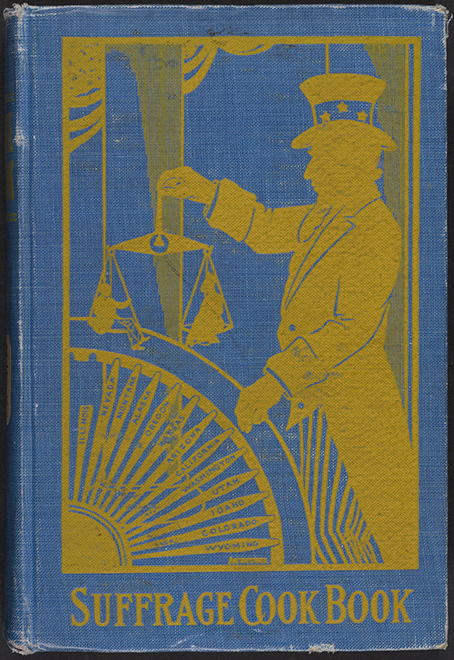

1915: The Suffrage Cookbook, L. O. Kleber (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania)

1915: Enfranchised Cookery, also known as Little Tastes of Enfranchisement, Hoar (Los Angeles, California)

1916: The Suffrage Cookbook; A Collection of Recipes, the Equal Suffrage League of Wayne County (Detroit, Michigan)

1916: Choice Recipes Compiled for the Busy Housewife, the New York State Woman’s Suffrage Party (Clinton, New York)

Each of these suffrage cookbooks took different approaches to the substance of the suffrage message. The Boston cookbook put its suffrage message at the end. The Los Angeles and Detroit cookbooks did not contain any specifically pro-suffrage materials, and thus their primary endeavor was perhaps more a tool for fundraising, while the Rockford, Washington, and Pittsburgh cookbooks interspersed pro-suffrage pieces in among the recipes.

The president of the Equal Suffrage Association of Rockford described the purpose of that “mixed” format, and indeed the purpose of the cookbook generally, as follows:

The object of the book was to get those women who think they have “all the rights they want” to read upon the subject, knowing that a woman will read a cook-book when she will not read anything else.

Whether it was a quote from a famous person or an essay on why a particular suffrage campaign had not resulted in victory, when the cookbooks contained pro-suffrage materials the message was usually forceful.

But sometimes, the touch was lighter. Just as Emma Smith DeVoe and Dr. Cora Smith Eaton praised suffragists as good cooks in their remarks to the press, the cookbooks themselves sometimes reinforced that image of suffragists as nonthreatening, domestic goddesses. The New York cookbook took that latter approach in its opening pages with a poem:

Where’er you find the suffragists

Efficiency you’ll find:

Their homes with neatness they prepare.

And with clear conscience forth they fare,

To stretch a pliant mind.

Learn ye of ways to labor save

In every walk of life:

Learn how to swiftly boil and bake

And leave no trouble in your wake.

Avoiding heat and strife.

Behold how wash day may become

A very holiday;

No more the sweltering kitchen claims

The time desired for other aims—

It’s quite the other way.

The Pittsburgh cookbook was notable for the inclusion of five “recipes” that are food for thought, rather than for cooking. They are for Hymen Bread, Anti’s Favorite Hash, Five Ounce Childhood Fondant (a sugary candy), Pie for a Suffragist’s Doubting Husband, and Scripture Cake. They are reprinted in the appropriate recipe section that ends each chapter.

The suffrage cookbooks are all collaborations, but their formats differ. As community cookbooks, they represent contributions from many people, each with her or his own voice. Probably because of their community-based origins, the suffrage cookbooks show a tendency toward light editing, if any, and a willingness to include recipes regardless of whether they add to the overall book.

Suffragists created their own cookbooks to gain entry into the homes of women.

Whether those characteristics demonstrate a sensitivity toward the contributors, a lack of time and attention on the part of the editors, or a bit of both, they result in duplication and inconsistencies in the larger cookbooks. Often there is more than one recipe with the same name and the organization can be puzzling. In the Detroit cookbook there are two recipes called “Italian Spaghetti,” included eight pages apart.

With similar though not identical ingredients and both containing meat, one is in the “Meats and Entrees” section, while the other is listed under vegetables. There are cookies in the cake section of the Washington cookbook, and two cookie recipes called Rocks, only one of which is listed in the index.

The Boston cookbook has five brown bread recipes, three of which are simply called “Brown Bread” and four recipes for how to make homemade yeast. In the case of the yeast recipes, maybe their contributors’ prestige had something to do with their inclusion. At least three of the four were from prominent women of the time: journalist and social reformer Mary A. Livermore; writer and editor Jane L. Patterson; and suffragist leader and editor of The Woman’s Journal, Lucy Stone.

Some of the cookbooks have a listed editor, while others do not. They range from a small pamphlet with only 15 baking recipes (if indeed you count that as a cookbook) to a tome with hundreds of pages and recipes that cover every course making up an elaborate meal, and every meal and snack from dawn to dusk. The books come from both coasts and the Midwest. Viewed together, they form a roadmap through America’s changing tastes and times over the 30-year span between the first and last suffrage cookbooks.

Suffragists saw an opportunity and they took it. Building on two concurrent developments in American cookbooks: the popularity of the breakout volume now known as the Fannie Farmer cookbook and the growth of community cookbooks, they created their own cookbooks to gain entry into the homes of women who were uninterested and maybe even hostile to the suffrage message.

After cooking the recipes, reading the advice about cleaning and healthcare, and maybe even laughing at a quip or two, those women were just a little less suspicious or hostile. And hopefully after serving their husbands (the voters) some delicious suffrage cookbook dishes, the suffragists had a better chance at turning that household into one with suffrage supporters.

__________________________________

Reprinted with permission from All Stirred Up: Suffrage Cookbooks, Food, and the Battle for Women’s Right to Vote by Laura Kumin. Published by Pegasus Books. © Laura Kumin.

Laura Kumin

Laura Kumin is the author of The Hamilton Cookbook: Cooking, Eating, and Entertaining in Hamilton’s World and runs the popular blog “Mother Would Know.” Kumin earned a law degree from Columbia Law School and practiced in Washington D.C. for more than two-decades. She lives in Washington D.C. where she now teaches cooking and food history.