On Trying to Write About Disordered Eating in the Age of Millennial Therapy Culture

Anna Rollins Wonders If Mothers Get Too Much of the Blame

In a recent New York Times opinion essay, “There’s a Link Between Therapy Culture and Childlessness,” Michal Leibowitz discusses our culture’s tendency to blame parents (let’s be honest here: mothers) for an adult child’s problems.

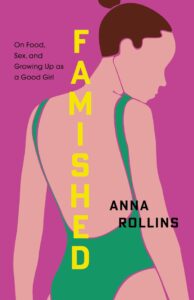

When I first handed beta readers a draft, Famished: On Food, Sex, and Growing Up As a Good Girl—a reported memoir which examines the rhyming scripts of evangelical purity culture and diet culture—the most common question I received was about my mom. She wasn’t missing from my narrative—far from it. But in a book that discusses my struggle with disordered eating, she also wasn’t highly implicated. And how could that be possible? If I had a problem, an eating disorder especially, surely that was mostly my mom’s fault—or, at least, that’s the logic our culture typically applies.

This assumption is not unfounded—many daughters trace their eating disorders back to their mothers. Still, I’ve mined my memories to find my mother’s missteps, and I’ve come up with very little evidence that she committed cardinal body image sins. My mom never dieted, nor did she criticize anyone’s bodies—mine, her own, or others’. After her sister died of stomach cancer at the age of 34, she did become more concerned with health, buying fewer processed foods. Was that it?

By writing a memoir that serves as a magnifying glass to my own demons, I am also turning attention toward my mother.

As my therapist has reminded me, a mental health condition—like disordered eating—is complex and cannot be tied back to just one thing. Even though I might like to identify the seed of my pain like a weed so that I could pluck it out of my life, this mindset focuses on individual organisms, rather than the ground into which we are all planted. Diet culture is part of the soil where we grow.

Still, millennials are steeped in therapy culture, and there is a tendency to blame parents for a child’s pain. Michal Leibowitz writes that our culture expects almost impossible standards for parenting. And while we should certainly have high expectations for parents—to provide basic necessities, safety, and love—no parent can safeguard a child from all forms of pain.

As Nicole Graev Lipson writes in Mothers and Other Fictional Characters, “There are some failures so profoundly damaging that they are beyond forgiveness—physical abuse, gross neglect—but those aren’t the sort of failures I’m talking about. I’m talking about the garden-variety missteps a mother is destined to make. I’m talking about the stumbles that qualify as failures only in a culture that treats mothers, in general, as the source of its shortcomings, and gives us license to point to our own mother, in particular, as the source of our own.”

This, I would argue, is not a glitch in the system, but part of its design. Rather than instructing children to look outside of themselves to a world filled with cruelty and injustice, we are encouraged to turn inward, to the self, and then smaller still, to the womb of one’s discontent.

But here’s what evangelical purity culture failed to acknowledge: we ultimately cannot control other people.

By writing a memoir that serves as a magnifying glass to my own demons, I am also turning attention toward my mother. As I scrutinize my own form in the mirror, a reader has also been trained by our culture to evaluate my mother—to consider all the ways she might not have measured up. Misogyny insists that the pain and problems that children face are due to some failure of the mother.

Still, it doesn’t escape me that something maternal hovers around my feelings with food. As I describe in Famished: On Food, Sex, and Growing Up as a Good Girl, motherhood reawakened my struggle with disordered eating—and yet, I keep insisting that my problems are not the fault of my own mother. I would, however, like to implicate our patriarchal culture: a place that provides little support for mothers while still holding them to impossible standards of perfection.

For the early years of a child’s life, a mother’s primary duty is to feed. First, with her own body. And always with incredible labor. A child’s hunger can feel constant, insatiable. And as a mother gives and gives, where is she to direct her own appetites? Can a good mother crave anything outside of her own children?

This is the weight of performing good motherhood—and it is heavy. I felt the load, and so, too, did my mother. My mother may not have perpetuated harmful beliefs about food or bodies, but she was immersed in the evangelical purity culture of the 90s, and the expectations for mothers there were not unlike the heavy load therapeutic culture insists upon today. The common denominator between the two? Patriarchy and hyperindividualism.

In the same way that evangelical purity culture taught me that I needed to control myself, not to be a stumbling block to men, it also taught my mother that she needed to parent perfectly so that she would raise well-behaved, God-fearing children. At my childhood church, my mom attended many group studies centered on parents “training a child up in the way she should go.” Good children were considered spiritual currency, an embodied sign that a woman was following God.

But here’s what evangelical purity culture failed to acknowledge: we ultimately cannot control other people. I’m not responsible for controlling men’s lust. My mother is not responsible for controlling all the many ways a child will experience pain. We can show love to others, but ultimately, we are only responsible for ourselves. In other words, we were taught no concept of bodily autonomy. This line of reasoning—that through personal rule following and self denial, one can shape happy and healthy children—is similar to what therapeutic culture places on intensive parents today.

When I portray my mother on the page, I want the reader to see her as a human being: one who strived and struggled, who wasn’t perfect but was always loving.

My mom was a wonderful parent—and not in a way that was punitive or especially rigid, either. She was present, patient, and loving. She baked scones after school and read books aloud and asked me questions about my day at school. And one of the ways she demonstrated her love was through sacrifice: she gave up a job outside the home and lived more frugally so that she could spend more time attending to all of her children’s needs.

She did all the things she was supposed to do and told to do, and she did it because she wanted the best for her children. I see this even more now that I am a mother myself. As I negotiate my identity and appetites apart from the children whom I love with my whole heart, I am able to see even more fully how much my mother loved me.

When I portray my mother on the page, I want the reader to see her as a human being: one who strived and struggled, who wasn’t perfect but was always loving. She, too, lived within the confines of patriarchal structures that made her feel the pressure to make her appetites, emotions, and desires disappear. In writing a memoir about disordered eating, the last thing I want is for a reader to scrutinize her form. That impulse—to monitor, surveil, and nitpick the appearance of women—is the very thing I am writing against.

__________________________________

Famished: On Food, Sex, and Growing Up as a Good Girl by Anna Rollins is available from Eerdman’s.

Anna Rollins

Anna Rollins lives and works in Huntington, West Virginia, where she has taught courses in composition and rhetoric, writing center studies, creative nonfiction, and text analysis for over a decade. Her work has appeared in outlets such as the New York Times, Slate, Salon, Electric Literature, Joyland, Newsweek, and the Today show. She is the author of the memoir Famished: On Food, Sex, and Growing Up as a Good Girl.