On Thomas Jefferson and the Little-Known Presence of Enslaved Muslims in the US

An Unexpected Letter to the Third President of the United States

On October 3rd, 1807, Thomas Jefferson’s evening at the President’s House was interrupted by the arrival of a cryptic note. Scribbled by a traveler from the “Territory of Louisiana,” this note was a single-page petition, pleading with the president for just one thing: “an interview.” I have “a matter of momentous importance to communicate,” the author insisted, but added no details. At its end, the note was signed with a name unknown to the president: “I. Nash.”

The evening of October 3rd, 1807, marked the end to a long day for Jefferson—a day that had begun on the road. That morning, the president had awoken at Songster’s tavern, more than 20 miles from Washington, facing the last day of his return trip from Monticello, his beloved “little mountain” home in the Virginian woods. This four-day journey back to the President’s House had proved more arduous, even dangerous, than expected.

It was “not as free from accident as usual,” as Jefferson informed his eldest daughter, Martha. On the way back to Washington, Jefferson’s horse, Castor, had almost drowned in the Rapidan River. The aging animal was barely saved by the president’s “servants,” who braved the waters to cut the horse loose from the carriage before he was swept under. To top it all off, Jefferson had lost his “traveling money” somewhere on the way, too.

Jefferson reached the President’s House before noon on Saturday, October 3rd. Any attempt to return to Washington routines, however, would be disrupted before the day was done. It had been more than two months since Jefferson had slept in his bed at the President’s House; but Jefferson did not even have the chance to settle in for the night before Nash’s unsettling request had arrived.

A devotee of clarity and order, Jefferson had every reason to be disquieted by Nash’s enigmatic note, which raised many questions. Who was this traveler—and why did he seem reluctant to write down the “matter” he wished to “communicate” in person to the president? Also troubling was the traveler’s origins in “Louisiana,” a vast “Territory” purchased by America four years earlier at immense cost and controversy—a largely uncharted US space whose recent upheavals had cost Jefferson sleepless nights.

I have “a matter of momentous importance to communicate,” the author insisted, but added no details.

By the time Jefferson opened Nash’s note, night was closing in, and Saturday would soon tick over to Sunday, October 4th. And yet, no Sabbath rest would be in store for Jefferson this Sunday. The mysteries of Nash’s note were simply too much for the president. Not long after reading the message he received, Jefferson decided to grant the traveler’s request.

Ira P. Nash arrived for his desired “interview,” and his note’s single promise proved true; he certainly did have an urgent and significant “matter” to “communicate.” Unfortunately, if Jefferson had hoped to settle matters by meeting this traveler from the “Territory of Louisiana,” he would be disappointed. Jefferson had not solved a mystery by granting Nash his interview, but uncovered a whole new series of puzzles.

By the evening of October 4th, 1807, Jefferson held in his hands strange writings carried to him from the country’s edges. Nash’s “matter of momentous importance to communicate” turned out to be two manuscripts—a pair of encoded communiqués written in coiled lines, and delivered to Jefferson from deep in the American interior.

Astonishingly, the two pages that Jefferson held on October 4th, 1807, were authored by two enslaved Africans, resisting their captivity in rural Kentucky. To receive writings by an American slave in 1807 was exceptionally rare; these writings handed to Jefferson were doubly intriguing, as he was unable to read them.

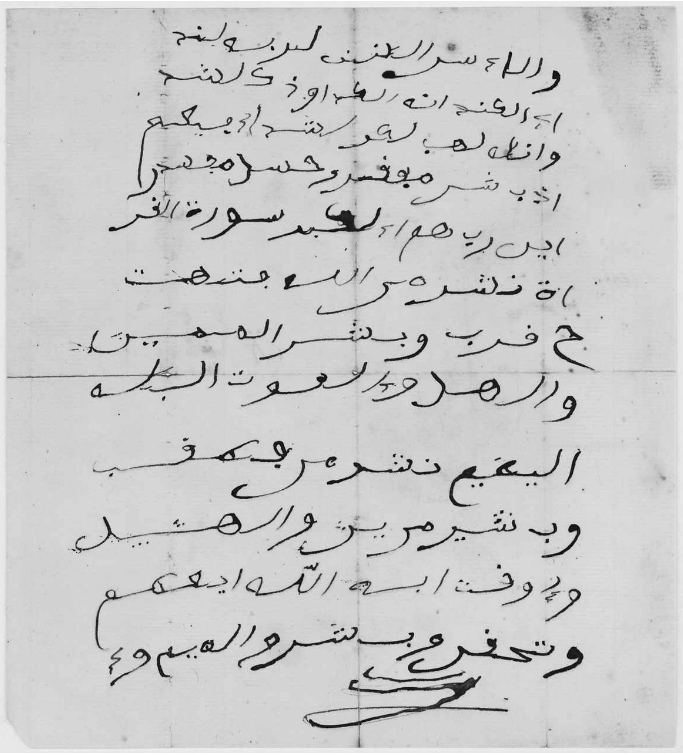

One of the two Arabic manuscripts delivered to President Thomas Jefferson in 1807, authored by fugitive Africans captured in Kentucky. Never before published, this image—reproducing “Page written in Arabic [October 1807],” Coolidge Collection of Thomas Jefferson Manuscripts, Massachusetts Historical Society—appears courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston.Penned by literate slaves seeking emancipation, the manuscripts conveyed to Jefferson from the far West were composed entirely in Middle Eastern letters. Peering down at two pages produced in America but illegible to its president, Jefferson scanned documents in a language that he could not decipher, but which he recognized all too well. Authored by enslaved Africans held in US captivity, the pages Jefferson scrutinized were written not in English, but wholly in Arabic.

One of the two Arabic manuscripts delivered to President Thomas Jefferson in 1807, authored by fugitive Africans captured in Kentucky. Never before published, this image—reproducing “Page written in Arabic [October 1807],” Coolidge Collection of Thomas Jefferson Manuscripts, Massachusetts Historical Society—appears courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston.Penned by literate slaves seeking emancipation, the manuscripts conveyed to Jefferson from the far West were composed entirely in Middle Eastern letters. Peering down at two pages produced in America but illegible to its president, Jefferson scanned documents in a language that he could not decipher, but which he recognized all too well. Authored by enslaved Africans held in US captivity, the pages Jefferson scrutinized were written not in English, but wholly in Arabic.

*

Nothing extraordinary was supposed to happen to Jefferson during the first days of October 1807—and, according to the countless Jefferson biographies and presidential histories so far written, nothing extraordinary did happen.

A midpoint in Jefferson’s second term, the opening to October 1807 is typically overlooked, seeming a brief calm amid the “Impressment Crisis” sparked earlier in the summer. On June 22nd, the British vessel HMS Leopard had attacked an American frigate, the USS Chesapeake, off the coast of Virginia. Suspecting that sailors on the Chesapeake were British deserters, the Leopard first bombarded the American ship and then boarded it.

Killing three of the US crew, the British seized four other sailors, “impressing” them into royal service. News of the “Chesapeake Affair” soon spread, provoking calls for retaliation from current Congressmen, and eliciting more nuanced responses from former US leaders. The previous president John Adams, still estranged from Jefferson after their bitter election battle in 1800, likened British impressment of deserters to the pursuit of fugitive slaves.

The “momentous” manuscripts put into Jefferson’s hands on October 4th were inscribed by Muslim slaves in America.

From his unhappy retirement in Massachusetts, Adams wrote to Benjamin Rush, highlighting the hypocrisy of American outrage, noting that “our People have Such a Predilection for Runaways of ever[y] description except Runaway Negroes.” The current president was infuriated too, of course. But a rash response suited neither Jefferson’s high office nor his cool temperament. More muted and moderate, Jefferson struck back at Britain with economic sanctions, leading to Congress’s “Embargo Act,” which was passed on December 22nd, 1807, exactly six months after the attack on the Chesapeake.

Biding his time in between summer’s open hostilities and this congressional action at Christmas, Jefferson soothed tensions at home, while seeking an apology from abroad, demanding the British admit their unjust “acts of aggression.” As Jefferson pursued political solutions and slow diplomacy, October 1807 began. Often neglected by biographers as an empty interval, this month’s first days saw Jefferson return from Monticello, arriving in Washington, where he would “wai[t] for a response to the protest he sent to England,” in Garry Wills’s words.

But October 1807 was no vacation nor vacuum for Jefferson. The president did wait in Washington for an answer from the British crown; but, instead, an entirely unexpected message arrived, which has stayed hidden for over two centuries. Sent not from a king across the ocean, the “momentous” manuscripts put into Jefferson’s hands on October 4th were inscribed by Muslim slaves in America.

Publicly, Jefferson sought to protect US freedoms in the autumn of 1807, ensuring US sailors were no longer detained as British deserters. Privately, at the same time, he received writings from African “runaways” wrested from their own country. While pleading with Britain to halt “impressment” of US citizens, the president was solicited by two men impressed into US slavery, who were, as Jefferson would later admit, “confined, on suspicion, merely because they cannot make known who they are.”

__________________________________

From Jefferson’s Muslim Fugitives: The Lost Story of Enslaved Africans, their Arabic Letters, and an American President. Copyright © 2020 by Jeffrey Einboden and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

Jeffrey Einboden

Jeffrey Einboden is Professor of English at Northern Illinois University and a 2017 Fellow of the American Council of Learned Societies. Einboden's most recent books include The Islamic Lineage of American Literary Culture (Oxford, 2016) and Islam and Romanticism (2014). He is the recipient of two fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, including a 2011 award supporting Einboden's recovery, translation and teaching of Arabic slave writings.