On the Yoruba Tradition's Complex Philosophical Heritage

Minna Salami on Myth, Religion, and Creative Expression

African knowledge systems have long provided a treasure trove of narrative for informing feminist ideas of knowledge. With the oldest civilizations in the world, Africa also has some of the oldest patriarchies, and so it is in the African continent that we find some of the oldest protofeminist narratives.

Women in traditional African society were not domesticated wives. They were traders, politicians, farmers, artists, and shamans. They were goddesses, witches, prophetesses, queen mothers, rain queens, pharaohs, and spirit mediums.

In African creation myths, there is no overarching supreme male god. If anything, there are traces of history that suggest that all Africans once worshipped a mother-goddess. That is not to say that there is always gender harmony among the pantheon of deities. Hardly! The gods get into kerfuffles concerning gender, as humans do, precisely so that they can show what happens when we don’t at least strive for harmony.

Moreover, the underpinning myths are egalitarian with respect to nature and species. The Yoruba gods, like many of their counterparts in other African religious systems (the earth goddess Asase Yaa in Ghana, Dzivaguru in Zimbabwe, Mamlambo in South Africa), are anthropomorphic representations of nature elements. A person invested in African spiritualities, therefore, treats nature with compassion. Similarly, animals are not viewed as inferior to humans because we all depend on life in an equal manner. Animals in African myths are companions who can even occasionally marry humans and produce children who are both human and animal.

Animals are also teachers, each with a specific lesson to teach. The tortoise, for example, shows how to watch out for dishonest and mischievous behavior by itself being guilty of that. Anansi the Spider in the eponymous Ghanaian tale similarly teaches about mischief by getting into mischief. It is not only in myths that Africans cohabit with animals. The Maasai people, who very rarely eat meat, have lived together with wildlife— giraffes, zebras, lions, leopards, and hyenas—for centuries and are not afraid of them. Unlike Europatriarchal Knowledge, historical African knowledge systems—like other indigenous ones— emphasize the value of harmony not only with other humans but also with nature and other sentient beings. African philosophy is a philosophy of interbeing.

African philosophies encourage creative expression (art, dance, ritual, sculpture, and so forth) as the highest form of knowledge.

Unlike some organized religions, African spiritual philosophies have no heaven or hell because, at large, they do not believe that there is such a thing as death. The souls of the departed are not punished for their sins in hell by a Manichean devil. In African spiritualities, the dead are supposed to “live” in transmigrated form or on nonphysical planes of the cosmos. According to Yoruba culture, the human spirit is triple layered—force or breath, shadow, and spirit (emi, ojiji, and ori). The Zulu have a similar triad—idlozi (guardian spirit), umoya (breath), and isithunzi (shadow)—and to the Igbo the human spirit is made up of uwa (visible world) and ani mmo (spiritual world). To ancient Egyptians, ba, ka, and akh were components of the soul that respectively represented the life force, the spirit force, and the unity of the two, which transcended this world and reached into the next. As a consequence, knowledge is not something that one must acquire and hoard during life, for wisdom and existence are infinite and eternal.

Significantly, African philosophies encourage creative expression (art, dance, ritual, sculpture, and so forth) as the highest form of knowledge. Ritual is reflective not only of spirituality but also of knowledge sharing. Deities are not simply divine energies, they are also representations of philosophy. Each god is a literation of a concept. For example, Shango, the spiritual embodiment of thunder, is also a historical reading of an African philosophy of social justice. Oya, goddess of tornadoes and protector of women, provides an interpretation of feminism in ancient Africa.

In her last book, Socrates and Orunmila: Two Patron Saints of Classical Philosophy (2014), the late Nigerian feminist philosopher Professor Sophie Bosede Oluwole offered a groundbreaking comparison between Socrates, the founder of Western philosophy, and Orunmila, the author of the Yoruba compendium of knowledge known as Ifa. The corpus of Ifa, which now also exists widely in written format, is a geomantic system consisting of 256 figures to which thousands of verses are attached. It has been stored through memory for millennia by traditional Yoruba philosophers known as Mamalawos and Babalawos (mothers and fathers of esoteric knowledge, respectively), who must study Ifa for fourteen years before being allowed to share its wisdom.

Oluwole wondered why Socrates, who did not produce any written work, can be considered the father of Western philosophy when Orunmila, who also transmitted his ideas to his disciples without writing them down, could not. Where Socrates famously said, “An unexamined life is not worth living,” Orunmila said, “A proverb is a conceptual tool of analysis.” Where Socrates said, “The highest truth is that which is eternal and unchangeable,” Orunmila noted, “Truth is the word that can never be corrupted.”

Where Socrates said, “Only God is wise,” Orunmila too addressed the limits of human knowledge in his statement “No knowledgeable person knows the number of sands.” Oluwole urged Africans to reclaim their philosophical heritage, contending that the body of knowledge she found in the Yoruba tradition was as rich and complex as any found in the West.

__________________________________

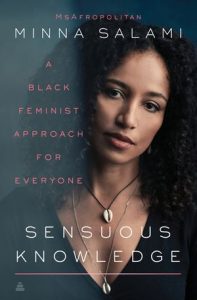

From Sensuous Knowledge by Minna Salami. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins. Copyright © 2020 by Minna Salami.

Minna Salami

Minna Salami, the author of Sensuous Knowledge, is Nigerian, Finnish, and Swedish author, blogger, and social critic, and international keynote speaker. She is the founder of the multiple award-winning blog, MsAfropolitan, which connects feminism with critical reflections on contemporary culture from an Africa-centered perspective. Listed by Elle Magazine as “one of twelve women changing the world” alongside Angelina Jolie and Michelle Obama, Minna has presented talks on feminism, liberation, decolonization, sexuality, African Studies, and popular culture to audiences at the European Parliament, the Oxford Union, Yale University, TEDx, The Singularity University at NASA, and UN Women. She is a contributor to The Guardian, Al Jazeera, and the Royal Society of the Arts, and a columnist for the Guardian Nigeria. She lives in London.