On the Writing Life and Safeguarding Privacy

Esi Edugyan on the Fraught Relationship Between the

Writer and the Void

I.

It is among the most fabled interruptions in literature: after an opium-induced reverie, Samuel Taylor Coleridge regained his senses to discover that an entire poem had written itself within his subconscious. It was one of those stunning and rare visitations—the whole and complete knowledge of a work—and with great urgency he sat at his desk to transcribe what had already been fully expressed within him. He had just written down the 54th line of the poem when there came a knock at the door: a person, come on business from nearby Porlock. The man would detain him more than an hour; and when Coleridge was finally left alone again, his recollections had completely vanished. He retained only the gist of the poem—a vague assembly of words, a wavering idea—a few scattered lines, the rest, as he put it, “passed away like the images on the surface of a stream into which a stone has been cast.”

And so the great “Kubla Khan” was destroyed at the very moment of its making.

Except it probably didn’t happen like that. Coleridge himself was known to embroider and invent—the crucial letter from “a friend,” for instance, that interrupts the eighth chapter of his Biographia Literaria was in fact written by the author himself. In the case of our person from Porlock, some scholars have suggested that Coleridge merely invented him to explain away the fragmentary nature of his great poem.

Yet whether a bogey, an unexpected occurrence, or an actual flesh-and-blood man, every writer fears these “People from Porlock”—which is to say, we fear the sudden, thought-scattering disruptions that hurt our work. Indeed, these days such disruptions seem the rule. One wants to board up the doors and dim the lights; one wants to drop the blinds, bind the shutters and mount a sign at the entrance saying, “The Wrong Door.”

Silence necessarily plays a large role in creation. Privacy is something other than silence, but is its near relative, I believe. Such notions may seem straightforward, at first glance. But in a world where our ideas of self-hood and privacy are ever-shifting, an examination of their role in creation seems valuable.

If it is true that every reader has a favorite book, it is equally true that every book has a favorite reader.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines silence as “the state or condition when nothing is audible; [the] absence of all noise and sound; muteness; taciturnity.” For the artist, I would add that silence is the state of being deep within oneself; it is the act of cutting out externals so that one may hear the internal. In this way, to greater and lesser degrees, Coleridge’s reverie is how all art gets made. We open a door within ourselves and leave it open, so that the unexpected and the unknown may fill us. I realize this nears the language of the sacred; but that seems fitting, as there is something of the sacrosanct in the act of writing. We take what is percolating and unformed, and through some mysterious process turn the void into utterance. The word “lost” is derived from the Old Norse word “los,” which literally means the disbanding of an army. This strikes me as the perfect metaphor for writing. We must break away from those we know, and go away alone, to lose ourselves in the unknown and miraculous.

II.

There is a second kind of solitude—a solitude other than the silence we carve out for ourselves amidst the roar of the greater world. It is needed if an artist is to stand behind his work, even in the face of the fiercest attacks. It is the solitude of certainty.

In a recent essay on silence, the novelist Shirley Hazzard tells a wonderful story that speaks to this necessity. To paraphrase: in 1572, the Renaissance artist Paolo Veronese was called before the Holy Office at Venice to defend himself against charges of blasphemy. He had painted a picture of the Last Supper, and along with the usual figures we expect to see in such a work, he had included random people in the background, dawdlers and loafers, men rambling by. There were people thoughtlessly scratching themselves, people with horrifying deformities, a man staggering with a nosebleed. These images, it was charged, had no place in a sacred painting.

Asked why he would depict such things, the artist replied: “I thought these things might happen.”

It hardly seems a viable defense, but as an artistic statement it is enormously resonant. Veronese, in his few words, was arguing for the idea that the principal role of art is to depict the world at hand faithfully, and this includes what is unsavory and ugly. Anything less than this is hagiography, or caricature.

If it is true that every reader has a favorite book, it is equally true that every book has a favorite reader. We write for everyone and fail to please across the board. And as artists, we must make our peace with the idea that this is alright; that in fact it is a welcome sign that we have challenged people, at least in the comfort of their sensibilities. I thought these things might happen, and so I wrote about them as faithfully as I could. This place of conviction can sometimes be lonely, but the work is all the truer for it.

III.

Privacy is something else again. It is interesting to note that the Chinese word that may come closest to the English word privacy, Si, means selfish. And indeed, there is that quality to it, a turning inward that is necessarily a rejection of others, the uncompromised protection of a sphere of silence from the violating whims of others. In our era of Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, notions of privacy are being shaped and reshaped by the hour, with some arguing that we live in a post-privacy world. The Internet yields all sorts of knowledge we are no better off for knowing.

The German futurist and film critic Christian Heller found himself relinquishing everything to this brave new world: he created a live site in which every quotidian detail of his existence was relayed online. “Privacy as a guaranteed personal space free from outside view is shrinking,” he explained. “Long-term privacy will survive only as an exception, as a special case in everyday life.” It was his belief that our only recourse is to confront the loss of privacy directly. One could read about what he ate that morning, how long it took him to get to work, et cetera. There were even links to his bank accounts, in which all his personal financial data was available for viewing. It was a staggering act of public intimacy, and like all long intimacies, gradually yielded to a wearying sense of banality.

I would argue that, above every other intrusion and interruption, it is a loss of privacy that has the greatest ability to destroy an artist. The knock at the door; the boiled-over kettle; the newborn’s cry—for most (not Coleridge, of course), these interruptions are all surmountable because they are fleeting. They are nothing when compared with the irrevocable loss of a much-needed private sphere of creation.

I think it would come as a surprise to most readers to learn that most writers in their middle to late careers regard with nostalgia their days of obscurity. I remember being puzzled when a writing professor sat us down and told us to savor our collegiate days, because our motives for writing would never again be this pure. We dismissed her as jaded, and longed for the days when we would see our words bound and prominently displayed in the local bookstore.

All of these tragedies are tragedies of exposure, and they speak to the very fundamental need for an area of silence, a room of, yes, one’s own.

How frustrated we were by that advice! So much of her meaning seemed to reflect her own anxieties over reviews and prize nominations. But I understand now too that what she was speaking of was a certain lack of privacy, a certain public spotlight that can begin to erode not only our artistic confidence but even motive, the very impetus for writing in the first place. I have spoken to a German writer who after publishing an international bestseller 13 years ago struggles to write, paralyzed by the idea of tarnishing his own reputation with an unlikeable follow-up. I have spoken to an American writer who was so badly shamed for an extra-literary occurrence that she cannot bring herself to enter again the public sphere. All of these tragedies are tragedies of exposure, and they speak to the very fundamental need for an area of silence, a room of, yes, one’s own.

As an extreme example, consider the fate of Elena Ferrante. The pseudonymous author of the Neapolitan novels takes as her subject the friendship between two bright girls in the harsh and limiting world of 1950’s Italy. The novels are brash and intelligent and full of knowing and utterly authentic situations. All of this creativity was taking place under the dome of the most strict obscurity—the only thing the public knew about Ferrante was that she was likely a woman, and even that was unverifiable. In the very few interviews she had given, Ferrante had suggested that her very anonymity was crucial to her artistic process. Only under the cover of a pseudonym did she feel liberated enough to write with honesty. Said Ferrante, via an email interview published in the Paris Review in 2015:

Once I knew that the book would make its way in the world without me, once I knew that nothing of the concrete, physical me would ever appear beside the volume—as if the book were a little dog and I were its master—it made me see something new about writing. I felt as though I had released the words from myself.

Then, in the fall of 2016, the dreaded knock came at the door, in the form of a journalist called Claudio Gatti. In an investigative feat that enraged many, he revealed the likely author of the Neapolitan novels to be a Rome-based translator, with some probable input from her novelist husband. Gatti was said to have been blindsided and shocked by the vehemence of the public’s reaction. He claimed he believed he was doing a public good, as Ferrante was slated to release a slim volume of memoirs that fall, which he had now revealed for a lie. Instead, he was castigated and jeered at on social media, cast unrecognizably to himself as the Person from Porlock, a lumbering, unthinking agent of creative destruction.

It is hard to know what to make of this man, Gatti. If he is sincere, then what he failed to understand was that the public had already consented to be lied to long ago. Indeed, the social contract between Ferrante and her readers was such that we accepted her constructed identity with all its attendant untruths. She had never claimed to have been born Elena Ferrante; we did not hold her to the fixity of that identity; we allowed her the fluidity to be what she needed to be. Where, in her relentless silence, we heard a voice—a true, authentic voice—Gatti saw only that last, curious definition of silence, “taciturnity,” as if there were some personal spite in her desire to remain out of the public eye. Perhaps the greatest revelation to come out of the controversy was the frightening realization of how far we have come from our cultural consensus that privacy is a fundamental right.

Given the way of the world now, how do we best find quietude and preserve it? Survival lies, I think, in understanding the varieties of solitude, knowing what is available to us, and what is out of our hands. It is in accepting that the void is sometimes an echo chamber, and knowing it will pass. It is trusting that the silence still exists, out there beyond the spectacle, and that despite the noise the words are still in us, waiting to be made whole.

__________________________________

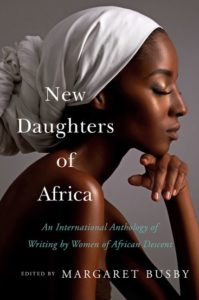

From New Daughters of Africa: An International Anthology of Writing by Women of African Descent. Copyright © 2019 by Esi Edugyan. Reprinted with permission by Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Esi Edugyan

A Canadian novelist of Ghanaian heritage, Esi Edugyan is author of three novels: The Second Life of Samuel Tyne (2004); Half-Blood Blues (2011), which won the Scotiabank Giller Prize, and was a finalist for the Man Booker Prize, the Governor-General’s Literary Award, the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, and the Orange Prize; and Washington Black (2018), which also won the Scotiabank Giller Prize, and was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, and the 2019 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction. In 2014, she published her first book of nonfiction, Dreaming of Elsewhere: Observations on Home. She lives in Victoria, British Columbia with her husband and two children.