On the Willie Nelson Country-Pop Crossover That Changed Everything

Michaelangelo Matos Goes Deep on One of 1980s Biggest Duets

“Willie was not . . . is not . . . And will not be signing autographs at the CBS booth.”

You can’t blame anyone for being confused. Just minutes earlier, the same voice boomed over the same PA system to the same teeming crowd that Willie Nelson was, in fact, sitting at the CBS Records booth with pen in hand, waiting to meet and greet his fans. There was no shortage of other stars at the Tennessee State Fairgrounds, but Willie was, without a doubt, the biggest country music star in America that year. In 1984, he released three studio albums, and by the time of his nonappearance at Nashville’s International Country Music Fan Fair, he had already scored the year’s top country hit, per Billboard: “To All the Girls I’ve Loved Before,” the most unlikely duet of the eighties.

“To All the Girls” had actually been Willie’s idea—he’d heard Julio Iglesias on the radio in London and his wife thought they’d sound good together. He agreed. “I phoned [manager] Mark Rothbaum,” Nelson said, “and said, ‘Try to find out who Julio Iglesias is and see if he wants to cut a record with me.’ Mark found Julio in Los Angeles. Julio said, sure, he’d like to do a song with me. I didn’t know Julio was selling more records at that time than anybody in the world.” Of course not.

“To All the Girls” was released as a single the month of the Grammys and took off like a rocket, but the prime had been pumped the previous October, when Nelson, resplendent in long red braids, red bandanna, T-shirt, and jeans, premiered the song on the Country Music Association Awards with the tuxedoed Iglesias. Julio, meanwhile, had no English-language LP at the ready, which from the retailers’ point of view was a massive fuckup: The single was outselling Willie’s album (which didn’t contain the song) two-to-one. Willie Nelson wasn’t selling “To All the Girls”—Julio Iglesias was. 1100 Bel Air Place finally appeared in August 1984.

Iglesias was as much a figure out of old-Hollywood-on-TV as Ronald Reagan—his theme song was “Begin the Beguine,” a World War II–era standard. Iglesias appealed to a similar demographic as Ronald Reagan—older women who liked being crooned to by a smoothie in a suit.

There was nothing sudden about Iglesias’s break into the American market. In March 1983, he’d played dates in New York and Los Angeles to great fanfare. At LA’s Universal Amphitheatre, booking agent Larry Vallon had suggested booking Iglesias months before only to be asked in return, “Do you want to keep working here?” Vallon was unfazed: “Although he was not well known in the Anglo world, this town has a 40 percent Hispanic population and it was for damn sure that they knew who he was.”

In 1984 all manner of crossover was on the mind of everyone in all manner of pop. Willie was a master of it and had been for some time. In the seventies he’d co-drafted the blueprint for country crossing over to the rock audience by playing by the latter’s rules, just as he now did with pop.

Nelson began in the fifties as a songwriter and turned performer in the mid-sixties, abandoning Nashville for Austin and signing with Atlantic Records in 1971. He cut Shotgun Willie in two days and watched it outsell his entire previous catalog in half a year. By 1974, he closed out his Atlantic deal with Phases and Stages, which sold four hundred thousand copies at a time when a Nashville album was lucky to reach the high five figures. A year later, on Columbia, Red Headed Stranger went gold; within a month, so did Wanted: The Outlaws, a compilation put together by RCA of old tracks from Willie, Waylon Jennings, Jessi Colter, and Tompall Glaser. The collection’s title would retroactively brand the entire scene.

In 1984 all manner of crossover was on the mind of everyone in all manner of pop.

By 1984, Willie had pulled off the most unheard-of type of crossover—completely ubiquitous, yet so subtle that no one minded. Permanently Zen or permanently stoned—it’s a sliding scale with Willie, as are all things. “What I always liked to do was be the guitar player,” he told an interviewer. “Somewhere along the way, I started being the singer. I’m not sure how that happened. I think one night the front man didn’t show up, and I wound up fronting the band and doing the singing. And I don’t know if that was really the best day of my life.”

Nelson worked his casualness like a runway walker works a pair of pumps. He was the wise man next door, doing business as one of the ten highest-paid performers in Las Vegas. When Brenda Lee came knocking on Willie’s door in ’84 looking for something personal she could auction off for charity at that year’s Fan Fair, she got a pair of sneakers and one of his famous red bandannas. It was certainly preferable to country comedian Jerry Clower’s contribution that year: a chain saw.

*

“To All the Girls” was one of the mid-80s’ ubiquitous country duets. In 1983, Kenny Rogers and Dolly Parton’s “Islands in the Stream” had been one of only two 45s to go platinum in the United States—one million sales. The song had been written by the Bee Gees; prior to it, Rogers had hit number one country by covering Bob Seger’s “We’ve Got Tonight” as a duet with the Scottish soft-pop singer Sheena Easton.

Dolly, like Kenny, had also gone pop, moving to LA and becoming a movie star. Before June was finished, her film career would suffer its first real dent, with the release of Rhinestone, a fiasco that Billboard’s “Nashville Scene” columnist Kip Kirby lamented “could set the image of country music—not to mention the South—back ten years,” under the headline: “Dolly, How Could You?”

But Dolly was omnipresent the week of Fan Fair, which ran June 4 to 10. On June 1, the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum opened a five-part exhibit of artifacts from throughout Parton’s career, from a 1946 photo of her birthplace in Sevierville, Tennessee, to the actual coat of many colors her mother made for her as a child, costumes from her movies, and over two hundred wigs.

Dolly was hardly alone in putting her life on display that week. Monday, June 4, saw the grand opening of Bill Monroe’s Bluegrass Hall of Fame and Museum. “They worked right up to the last minute to get this finished for Fan Fair, they sure did,” Monroe told The Tennessean. “I’m very pleased.” The next day, six names were added to the Walkway of Stars at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, with the crowd beside themselves over the Oak Ridge Boys. And on Thursday, June 7, Barbara Mandrell would spend the day with her fans at her new museum, Barbara Mandrell Country.

It had been a slow climb from the 1972 opening of Opryland, which by 1984 was drawing two million people a year. “Subsequently Opryland begat the Opryland Hotel,” wrote Nashville! magazine’s Miriam Pace that June. “The hotel begat the lucrative convention business; the convention begat the current hotel/motel boom on Briley Parkway (where eight new operations have been planned in the past three years) . . . [and] the multiple births of acres of ‘entertainment complexes’ in the area: [Conway] Twitty City and Music Village (a hundred-million-dollar development of star museums and homes on one hundred and thirty acres in Hendersonville), the Cajun’s Wharf Music Complex (a seventeen-acre, eight million dollar development on Cowen Street), and Country Music World (four hundred thirty-five acres around Foxland Hall in Gallatin).”

By 1984, Willie had pulled off the most unheard-of type of crossover—completely ubiquitous, yet so subtle that no one minded.

By the mid-80s, tourism was Nashville’s largest of what Pace referred to as “the offshoot industries spawned by country music”: “During 1982, 7.4 million people dropped in on our city.” Don Belcher, director of research for the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce, said, “We’ve got millions of people who come to this city each year just begging us to take their money. All they ask is that maybe we smile back at them.” Fan Fair only had a fraction of that, but they counted. Terry Clements, Metro director of tourism, told the Nashville Banner that the entire city would “reap the harvest” from Fan Fair. He elaborated: “The money tourists spent this week will be turned over many times in the coming weeks.”

Fan Fair had begun as the offshoot of the International Fan Club Organization (IFCO), the brainchild of three sisters from Colorado, Loudilla, Loretta, and Kay Johnson. Loudilla, the eldest, had joined the George Jones Fan Club in 1960; the three of them, after watching him perform in Colorado Springs, drove to a radio station two hours from their home where he was spinning records, including Loretta Lynn’s “Honky Tonk Girl,” made for the small Zero label while Lynn was still living in Washington State. Loretta Johnson, because she shared her name, was the first to write Lynn; by 1963, she’d started a Lynn fan club. The IFCO followed in 1965; by 1984 it was overseeing over 250 country music fan clubs around the world.

__________________________________

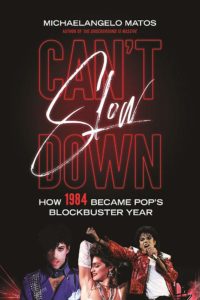

From Can’t Slow Down: How 1984 Became Pop’s Blockbuster Year by Michaelangelo Matos. Used with the permission of Hachette Books. Copyright © 2020 by Michaelangelo Matos.

Michaelangelo Matos

Michaelangelo Matos is the author of The Underground Is Massive: How Electronic Dance Music Conquered America (Dey Street, 2015) and Sign 'O' the Times (Bloomsbury, 2004) and contributes to The New Yorker. He lives in St. Paul, Minnesota.