On the Ways We Read (and Are Written To)

Damon Young on the Rarity and Fragility of Words on a Page

Jean-Paul Sartre, in What is Literature?, wrote: “There is no art except for and by others.” The philosopher’s argument was not that authors cannot enjoy writing for themselves; that every word is dashed off, hand aching, for tyrannical editors and audiences—what Henry James described in one letter as “the devouring maw into which I. . . pour belated copy.” Instead, Sartre’s point was that the text is only ever half finished by the writer. Without a reader, the text is a stream of sensations: dark and light shapes.

This does not mean ordinary life is a play of dumb necessity. Sensation always has some significance for humans—we are creatures of meaning, and the universe is never spied as a naked fact. But the world writ large does not refer to things fluently; the suggestions are often vague. “The dim little meaning which dwells within it,” wrote Sartre of everyday sensation, “a light joy, a timid sadness, remains imminent or trembles about it like a heat mist.” Ordinary life has a hazy atmosphere to it, whereas language illuminates brightly and sharply.

The letters achieve this by pointing beyond themselves—we read through the text, not off it. “There is prose when the word passes across our gaze,” said Sartre, quoting the poet Paul Valéry, “as the glass across the sun.” Words are portals of sorts: they frame reality, and become invisible as we peer.

Not all texts are as transparent as Sartre’s ideal prose. Poetry can be more opaque. Take Seamus Heaney’s “The Bookcase.” It refers literally to the poet’s library, but it also makes a spectacle of the English tongue. “Ashwood or oakwood? Planed to silkiness / Mitred, much eyed-along, each vellum-pale / Board in the bookcase held and never sagged.” Alliteration, rhythm, metaphor: this is about a thing and its resonances, but it is also about language. Poetry puts on a show of words, just as painting displays color, and music sound. Poetic phrases, wrote German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer, “haul back and bring to a standstill the fleeting word that points beyond itself.”

Language can be translucent like amber or clear like Valéry’s glass, but staring through it always asks for effort. Inscriptions or projections become words, which have meanings alongside their tone and cadence. This is what I first recognized in Sherlock Holmes: reading is always a transformation of sensation into sense. “You have to make them all out of squiggles,” poet D Nurkse wrote, “like the feelers of dead ants.”

For the reader, this means rendering a world: the intricate ensemble beyond the page. When Conan Doyle writes that the sun is visible “through the dim veil which hangs over the great city,” I recreate London. Not only the sky’s spray of yellow and grey, but also the coal and commerce that make the metropolis “great.” The newspaper reporting the death of Sherlock’s client also evokes a community of middle-class readers from Cornwall to Northumberland, all participating in the imagined community of print. Waterloo Station, to which the victim was hurrying, suggests steam trains across England: taking passengers and parcels of The Times for men like Watson to read. All this I project behind the foreground prose. “The objects represented by art,” as Sartre put it, “appear against the background of the universe.” I piece together a cosmos from the author’s fragments.

What this all reinforces is that writing cannot make anything happen. As an infant, earlier editions of The Celebrated Cases of Sherlock Holmes were wholly opaque to me: blocks of chewable stuff. And as an 11-year-old I was not forced to imagine Holmes in his “velvet-lined arm-chair,” pushing blow into his blood. I had to commit myself to the text; to consent to a kind of active passivity, in which I accepted Conan Doyle’s words, then took responsibility for giving them some totality.

“The ubiquity of script masks the rarity and fragility of reading. What you are doing right now is, cosmically speaking, against the odds.”

Reading requires some quantum of autonomy: no-one compels me to envisage their words. They are, at best, an invitation. Sartre phrases this as an “appeal,” and the idea makes sense of how little necessity is at play. Reading is always a meeting of two liberties: the artist’s and the audience’s.

In this light, it is false to say that my childhood is in my pine bookcase. It can seem this way, because old tomes prompt nostalgia. As Marcel Proust noted in On Reading, some memories of youth are lost in daily life, but regained in the pages we read during those years. “They are the only calendars we have kept,” he writes, “of days that have vanished.” But if I never read these volumes again, the recollections can become Proust’s temps perdu: lost time. Whatever is most animated in the written word is only revived “when the dead letter comes again into contact,” as Hannah Arendt put it, “with a life willing to resurrect it.”

This is a more general point. My books are just objects alongside other objects: pigment, glue, dead cellulose and cowskin. If they do not enter into specific relations with very specific objects—literate humans—then reading never happens. Reading in general might one day cease altogether. If the species known to itself as Homo sapiens becomes extinct, all these readable things—books, newspapers, tweets, billboards, roadside signs, subatomic initials on copper—will no longer be texts, strictly speaking. They will be lived in, eaten, buried, climbed upon, oxidized, but not read.

The ubiquity of script masks the rarity and fragility of reading. What you are doing right now is, cosmically speaking, against the odds.

*

An assumption: you enjoy this unlikely activity. For most readers, this is an untroubled devotion. It is easy to identify with playwright Tom Stoppard, who spent his bus fare on second-hand books, “preferring the devil of hitchhiking to the deep blue sea of enduring half an hour bookless.” Identifying why we care is less straightforward.

Most obviously, reading is educational. This is why my parents intoned Blyton nightly, and why I spent so many afternoons sounding out Miffy at the Gallery to my daughter. An early introduction to the written word provides an enormous personal and political advantage. Researchers Anne Cunningham and Keith Stanovich reported that children’s literature encourages a profuse vocabulary: 50 percent more unusual words than the chatter of university students, or the most popular television. This lexical abundance then encourages more reading: positive feedback that begins well before school, and lasts a lifetime. Along the way, reading piles up vast stocks of otherwise obscure facts. Political gambits, scientific hypotheses, historical dramas: these become the taken-for-granted ground upon which citizens walk. Texts help to lay this foundation in childhood.

The written word can also boost psychological health and social connection. Studies suggest that a lifetime’s reading, alongside company and exercise, can lessen dementia risk. Emory University researchers reported that participants reading a novel had more neural connectivity in the language and sensory motor regions of the brain. Lead author Gregory Berns wrote that “reading a novel can transport you into the body of the protagonist.” What seems like an ethereal pursuit actually offers a visceral commingling. Research also suggests that literary fiction can contribute to a theory of mind, the idea we have of others’ mental states. A New School for Social Research study revealed that reading authors like Don DeLillo or Anton Chekhov caused a brief but measurable jump in emotional intelligence: in this case, judging a stranger’s mood from their eyes.

While it is flattering for bibliophiles to believe their pages guarantee a payoff, skepticism is warranted. Regular jogging might prevent mental decline far more reliably than reading Haruki Murakami on jogging. Some studies have small sample sizes or vague measures: brain scans say nothing about behavior, or whether reading has unusual effects next to other pastimes. Others generalize too boldly about genres: does Chekhov have the same effects as Kazuo Ishiguro or Iris Murdoch? And even if DeLillo helps me guess someone’s humor, I can be correct without being sympathetic or caring—bastards enjoy fiction too. (Some are authors.) Reading has demonstrable benefits, but it is not a machine for producing geniuses or saints.

This outlook also values reading as a means to an end. This is important, and covers many kinds of genuine worth: historical, philosophical, culinary, sexual. I pick up Conan Doyle to learn about Victorian London or Immanuel Kant to better comprehend modern ethical theory. Some read for symbolic capital, others for last-minute dinner recipes, others for orgasm (“a sort of ecstasy came over me after I had read for about an hour,” said the heroine in 18th-century French bestseller Thérèse the Philosopher). There is no harm in highlighting the benefits of text, whether straightforward or subtle, scholarly or biological. But this approach can ignore how reading is an end in itself: an opportunity for experiences.

__________________________________

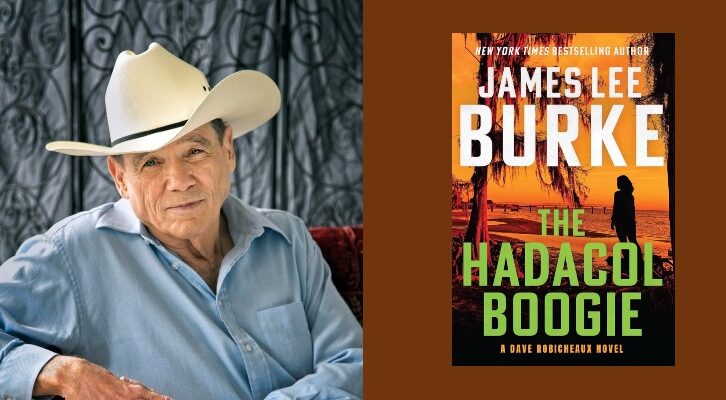

From The Art of Reading. Used with permission of Scribe. Copyright © 2018 by Damon Young.

Damon Young

Damon Young is a prize-winning philosopher and writer. He is the author or editor of twelve books, including The Art of Reading, How to Think About Exercise, Beating and Nothingness, and Distraction. His works have been translated into eleven languages, and he has also written poetry, short fiction, and children’s fiction. Young is an Associate in Philosophy at the University of Melbourne.