On the Valuable Writing Lessons I Learned as a Television Reporter

“I’m conscious of the economy of words, never saying more than what’s necessary.”

For more than a decade, I had a front-row seat to the biggest stories making news—from the killing of Jeffrey Dahmer in a Wisconsin prison to the 2000 presidential election recount in Florida between George W. Bush and Al Gore. I went into journalism with wide-eyed idealism, wanting to tell stories that held the powerful accountable and gave a voice to everyday folks. What I didn’t count on were the storytelling and writing lessons I’d pick up as a television reporter that would serve me well years later as a novelist.

1. Seeking truth

In college journalism classes, we heard over and over again the old axiom that “If your mother says she loves you, check it out.” Journalism put me on a path of relentless pursuit of truth, objective truth. When possible, I interviewed people on every conceivable side of a story—Democrats and Republicans, the accuser and the accused—to get to the facts, the truth. What I learned was that truth can be murky, and that it largely depends on one’s individual perspective or worldview. In my interviews, I tried to be fair and balanced in my coverage, but I discovered that truth could be variable.

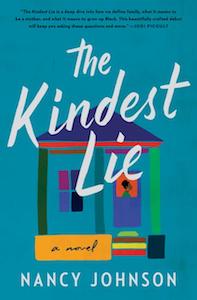

The bitter divide between Black and white America during the 2008 presidential election inspired my debut novel, The Kindest Lie. I brought a range of Black experiences to the page, from a displaced auto worker and a frustrated hair stylist in a small Indiana town to a chemical engineer in Chicago who’s not advancing in her career. Each of them has a unique experience of race.

While anti-Black racism has a 400+ year history in America, I was curious to explore what a segment of working-class white America believed to be true about their circumstances and trajectory in this country. I’ve been asked in interviews about the definitive truth of what I learned writing this book. Truth can be as varied as people’s lived experiences. What I know for sure is that there are universal truths about love, forgiveness, and sacrifice that we all share, and they are the threads that connect all of my characters. Journalism put me in the hunt for truth, but fiction forced me to look deeper to find the layers of meaning in that truth.

2. Building empathy

I’ll never forget hearing Oprah tell the story of why she left news to start her own talk show. During her reporting days, she often cried with the victims of tragedies, and newsroom management insisted she toughen up. She never did. Instead, she became the queen of daytime television, inspiring people around the world to emote. I had a similar experience. Early into my first television reporting job at a small, independent station in Kenosha, Wisconsin, I covered the story of a star high school football player who was killed by gang violence. I remember sitting with his mother in their kitchen crying alongside her.

At first, I felt embarrassed to have been so unprofessional on the job. But when I watched the replay of that story, the unbearable heaviness of that mother’s pain was palpable. She had been vulnerable with me, and my empathy toward her gave the viewers a way into her story. Over the course of my career, I interviewed hundreds of people who lost loved ones, homes, and livelihoods. I think the viewers cared because it was obvious that I did.

The poet Robert Frost is quoted as saying, “No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader.” If the most heart-wrenching scenes in my novel don’t gut me, something’s wrong and I can’t expect the reader to feel anything.

I’m not a mother, but in my novel, I take readers into this tiny, suffocating bedroom in the throes of August heat where 17-year-old Ruth Tuttle gives birth. In the midst of a painful childbirth, she’s wrestling with the decision of whether or not to keep her baby or walk away from him to pursue her Ivy League dreams. Just as I would’ve been as a journalist, I was in that bedroom with her, holding her sweaty hand, the anguish of her predicament washing over me.

3. Paying attention to detail

Some of the best award-winning photojournalists in the business taught me to turn away from where every other camera is pointing at a big news event. Looking behind me, I always found the real story. On the scene of a raging fire, most reporters trained their eyes on the blaze, the skeleton of the home, and the arson investigators at the scene. I’d often look on the ground and find the stuffed animal in the rubble and search for the story of that child. Or I’d see a diamond ring shining through the ashes and understand there was an untold love story.

Those are the details I bring to novel writing—it was important for me to tell the reader that the overwhelmed shopkeeper character, Lena, smoked Newports and that Ruth’s hair smelled of “avocado and coconut and promise” the night of her Obama election party. Ruth’s brother, Eli, lost his job working the production line at the plant and began spending way too much time on a barstool.

When I was creating his character, I turned to Facebook to crowdsource the brand of beer he drank—Bud, always a Bud. Ruth’s grandmother, Mama, washed her dishes and clothes by hand, and heated food in the oven because she didn’t believe in dishwashers, washing machines, or microwaves. We learn so much about this proud, 78-year-old woman who is defined by the things she doesn’t believe in.

Truth can be as varied as people’s lived experiences.

Every seemingly small detail or moment carries meaning, and those astute observation skills of reporting taught me that.

4. Focusing on the individual to explore large, complex issues

Much of The Kindest Lie takes place in Ganton, Indiana, a fictitious factory town where the auto plant closed during the Great Recession of 2008. My first introduction to economic scarcity in a city like that came during my reporting days in Kenosha. About six years before I moved there, the Chrysler plant closed, and thousands of jobs disappeared.

I remember the gaping hole of despair in that community with an empty assembly plant sitting in the heart of town, its hum silenced. I interviewed many displaced factory workers struggling to support families and reinvent themselves. Their interior lives informed the characters of Eli and Butch in my book—two proud men, one Black and one white, both losing their jobs at the plant. Toxic masculinity consumed them, but so did a fierce love for their families. The financial strain they endured exacerbated racial tension between them. The people I met on news stories were rarely heroes or villains; they were just everyday folks trying to make it the best they knew how. I bring that understanding and empathy to the characters I create.

When I sat down to write my novel, I knew I wanted to tackle big, important issues, but I wasn’t aiming for a treatise. I had learned in my journalism days that the way into any macro topic was through individual stories. My obsession with politics began in 2000 when I was reporting for the ABC affiliate in West Palm Beach, Florida. The infamous butterfly ballot in the presidential race that year between George W. Bush and Al Gore came from Palm Beach County, and suddenly, I was at the center of the biggest story of my career. I sat in many Floridians’ living rooms that election cycle talking about the impact of that election on their lives. The individual stories of voters brought the issues to life. The personal was always political.

The next time I felt the weight of history on an election was when Barack Obama became President. That election—the fragile hope—inspired me to write The Kindest Lie. I brought the racial and economic strife of that time period to life through the lens of Ruth, Midnight, and their families. It had long become clear to me that you often have to go narrow and deep to see the bigger picture.

5. Writing for the ear

Television taught me to listen to good writing, to train my ear for the rhythm of language. Every day when I sit down at my computer to compose a scene, I read aloud what I wrote the day before. I listen for discordant notes or a turn of phrase that doesn’t sound right. When I hear myself reading dialogue, it’s easy to pinpoint what sounds stilted. We all know how real people talk; that’s the authenticity I was going for. The exposition should have a flow, too, and not sound redundant. That’s why I vary the length of sentences. If the scene is meant to be tense, I go with shorter lines and more white space. In my TV scripts, the line breaks mattered; they told me when to take a breath, and visually, I knew when and how to hit those impact lines. Same with my novel manuscript.

Broadcast writing is also crisp and concise. My fiction is spare, and I’m conscious of the economy of words, never saying more than what’s necessary. I know when to get out of the way of a good story, to end a scene or a book when nothing extra is left on the bone—only the essence of what needs to be said.

__________________________________

The Kindest Lie is available from William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2021 by Nancy Johnson.

Nancy Johnson

A native of Chicago’s South Side, Nancy Johnson worked for more than a decade as an Emmy-nominated, award-winning television journalist at CBS and ABC affiliates nationwide. A graduate of Northwestern University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, she lives in downtown Chicago and manages brand communications for a large nonprofit. The Kindest Lie is her first book.