On the Upstart NYC Alt Weekly That Gave Us Armond White

Jim Knipfel Recalls the Film Desk at the NYPress

Around 1995, the NYPress had finally earned a growing reputation as a viable, cranky, smart and cynical alternative to that dusty and self-righteous The Village Voice. You never knew what you were going to find in any given issue of the Press, but you could rest assured there would be something that made you laugh really hard or pissed you off to no end.

The paper began to grow considerably, with more ads, more pages, and more writers and artists to fill those pages. C. J. Sullivan, a court officer and former cop, came aboard to write Bronx-based crime and human interest stories. Jonathan Ames wrote about his assorted fetishes. Aspiring actress Amy Sohn chronicled her endless sexual misadventures. Alan Cabal channeled Hunter S. Thompson while writing about Satanism and conspiracies. Little Ned Vizzini, who started at the Press when he was about fifteen, documented life as a gifted, overachieving New York teenager. Mistress Ruby offered accounts of her day job at an upscale dungeon, George Tabb covered the punk scene, David Lindsay wrote about patents and inventors, and William Monahan wrote long, brilliant and wickedly funny essays about whatever the hell he wanted. The paper also contained a good deal of serious political commentary, but again commentary that ran the gamut from anarchist to ultraconservative, including weekly columns by notables like Christopher Caldwell and Alexander Cockburn.

Despite my shaky memory to the contrary, Matt Zoller Seitz joined Godfrey Cheshire on a weekly basis in October of 1995 with his review of Paul Auster’s improvisational Blue in the Face. Together they made the film section a centerpiece of any given issue, garnering a large percentage of the both enraged and laudatory mail in the likewise growing and crazy letters section.

Godfrey was a hip bespectacled Southern gentleman, polite, direct and charming. Along with his breadth of knowledge about the film business, he was friends with R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe and quite familiar with the ins and outs of the Southern music scene. Not only was he the first American critic to call attention to the bourgeoning Iranian film industry (often reporting directly from Tehran), but over there he was considered a celebrity.

Matt was younger, a product of the Star Wars generation, but equally sharp and extremely funny. While Godfrey focused more on indie arthouse cinema, Matt was a genre specialist. I could talk to Matt about most anything across the vast spectrum of American pop culture—not just films, but TV, music, books, whatever. Long before Paul Thomas Anderson appeared on the scene, I remember the two of us trying to decide what living director would be best suited to adapt a Thomas Pynchon novel (Matt’s vote was for Cronenberg, mine for Craig Baldwin). His frighteningly hilarious review of the big-budget all-star Michael Crichton trainwreck Sphere remains a personal favorite, a review that stuck with me for years after first reading it.

Writers like Matt, Godfrey, Strausbaugh, Monahan and the rest were so damnably talented and intelligent, readers, whether agreeing or pulling out bloody clumps of hair, were forced to pay attention and respond to what they were reading.

The most important thing to keep in mind through all this is that at the NYPress, despite all its eccentricities and drunken tomfoolery, the writing was always paramount. Regardless what you had to say, if you didn’t say it extremely well and with a certain unblemished pizzazz, you’d never make it past editors John Strausbaugh or Sam Sifton. We could have run semi-literate rants about city council or some local band, just piled up the obscenities and crude insults, but that’s too cheap, and too easy to ignore. The fact writers like Matt, Godfrey, Strausbaugh, Monahan and the rest were so damnably talented and intelligent, readers, whether agreeing or pulling out bloody clumps of hair, were forced to pay attention and respond to what they were reading.

In May of 1997, the editors announced they were bringing on a third film critic. Things were going gangbusters at the Press. They were exciting times to be around the office. The paper was still growing, and we’d even forced the Voice to go free in order to compete. Still, there was a bit of head-scratching at the announcement. Godfrey and Matt seemed to have things well in hand, everyone liked and admired them a bunch, so why bring in this Armond White?

I admit being a bit startled when he first entered the office. Armond can be an imposing figure if you don’t know him—a tall and burly man in a trenchcoat, mostly bald with thick glasses. He had an odd way of talking, both shy and deeply self-assured. I sometimes had the odd feeling when we spoke he was actually talking to someone else who wasn’t there. I got over that, though, and in the years that followed we talked quite a bit, mostly about goings on at the paper and, of course, films.

Born in Detroit, Armond first appeared on the New York scene as editor of the Brooklyn’s City Sun. An African-American film critic, his thought-provoking, unpredictable perspective quickly established him as the go-to critic among his peers, who always took notice of his challenging mindset. Writing from his own unique perspective, he also became one of the city’s most unpredictable voices, often flummoxing readers and fellow critics alike by, among other things, publicly turning against Spike Lee after hailing Do the Right Thing, championing Steven Spielberg’s The Color Purple, and pointedly attacking fellow critics for bad faith reasoning. Race aside, Armond was a staunch individualist, unswayed by the general consensus about this or that film.

It turns out Godfrey was the one who recommended Armond in the first place, the two coming to know each other through the New York Film Critics Circle. In accordance with the well-established attitude of the paper, Armond was seemingly brought on to piss the hell out of cinephiles, casual moviegoers, and even people who hadn’t seen a new film in years. Being the genetically contrary sort, he seemed to do this with ease. An intellectual African-American film critic who attacks African-American filmmakers while heaping praise on Steven Spielberg? That’s just crazy talk! Why, I oughtta…

But Armond wasn’t merely a provocateur—again that would be too easy. He was extremely intelligent, had a fierce command of the language, and knew his pop culture history as well as anyone, but wrote from a singular point of view which, while absolutely valid, ran counter to most mainstream sensibilities. As controversial as his reviews could be (when comparing Titanic and Amistad, he described the former as “a film for people who would rather watch white folks die than black folks live”), he could always cogently defend his arguments.

In a blink, compared with the Voice, the Times, or any other major publication with multiple film critics, the press could lay claim to having what was unquestionably the most unique trio of radically distinct voices in town, which was reflected on those rare occasions when all three were allowed to review the same film.

The film section became a very lively place, with all three taking jibes at one another in their reviews. Although I was never in attendance, I’m told the regular meetings in which they divvied up who got to review what films in the coming weeks could get mighty heated at times. Still, the mutual respect they felt for one another was always evident. Most of the time, anyway.

__________________________________

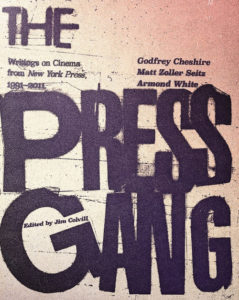

Excerpted from Jim Knipfel’s introduction to The Press Gang: Writings on Cinema from New York Press, 1991–2011 by Godfrey Cheshire, Matt Zoller Seitz, and Armond White; edited by Jim Colvill. Published by Seven Stories Press (2020).

Jim Knipfel

Jim Knipfel is an American novelist, autobiographer, and journalist.