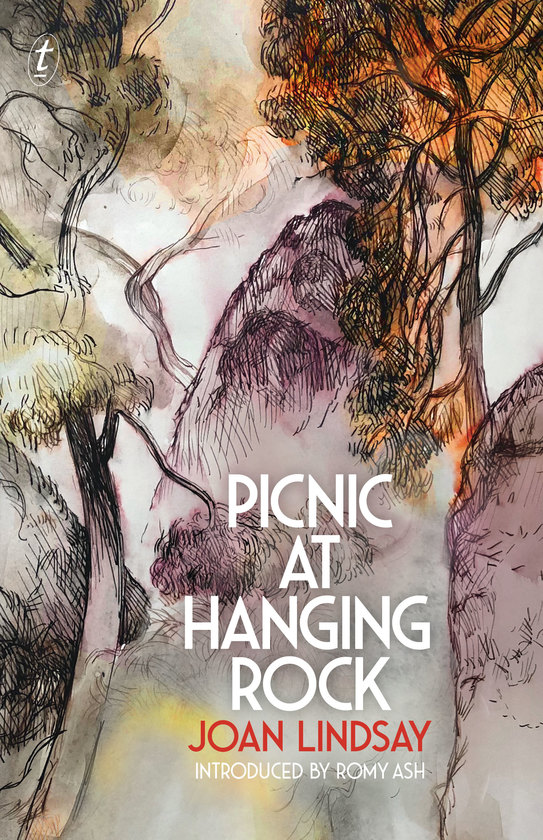

On the Unpublished Ending of Picnic at Hanging Rock, and Other Mysteries

Romy Ash Wanders Through an Iconic Australian Novel

I like to walk at Hanging Rock, in the Macedon Ranges in Victoria. The rocks there do unusual things to sound. Noisy revelers might be hidden around a corner, unheard until you come, suddenly, upon them. The way that sound travels makes for an eerie atmosphere.

The experience of being within this place is layered with story: with Joan Lindsay’s mystery, with Peter Weir’s dreamy lens; white frills against the blue-green of eucalypt. I first came to Lindsay’s Picnic at Hanging Rock (1967) through Weir’s 1975 film. I wondered, in the fuzz of my own early adulthood, if Lindsay’s novel was based on a true story. This question is part of the book’s strangeness. There’s a wondering to the novel—what is real, what is imaginary—as there is in the great hulking rock at its center.

I read Lindsay’s novel as I would a thriller. Often described as Australian Gothic, Picnic at Hanging Rock is a plot-driven murder mystery, with the disappearance of three young girls and a governess standing in for the murder. The Valentine’s Day picnic that opens the story sets a series of dark happenings into motion. The novel concerns itself with ripples, reverberations of the dreamlike event; to read it is to search for answers, just as the characters left behind search for the missing. Some are driven mad; others to extremes, to love, to their own deaths. Their fates seem as inevitable as those of the girls who were drawn to the rock never to be seen again, as if pulled, “hardly walking—sliding over the stones on their bare feet as if they were on a drawing-room carpet, Edith thought, instead of those nasty old stones.”

Picnic at Hanging Rock was written quickly, after Lindsay had a particularly vivid dream, and it’s a dream state that permeates the narrative. The characters fall in and out of sleep, daydreaming in a way that suggests they may have woken up in a different reality. We see this just before the girls disappear:

Miranda was the first to see the monolith rising up ahead, a single outcrop of pock-marked stone, something like a monstrous egg perched above a precipitous drop to the plain. Marion, who had immediately produced a pencil and notebook, tossed them into the ferns and yawned. Suddenly overcome by an overpowering lassitude, all four girls flung themselves down on the gently sloping rock in the shelter of the monolith, and there fell into a sleep so deep that a horned lizard emerged from a crack to lie without fear in the hollow of Marion’s outflung arm.

The descriptions of the girls have the same level of hallucinatory detail as Lindsay gives the rock, the trees, the animals. Marion’s torn muslin skirt is “fluted like a nautilus shell.” The environment is depicted as menacing, impenetrable and unknowable, as well as exquisitely beautiful, lovingly rendered in minute detail: “In the colourless twilight every detail stood out, clearly defined and separate. A huge untidy nest wedged in the fork of a stunted tree, its every twig and feather intricately laced and woven by tireless beak and claw.”

When I last walked at Hanging Rock, I heard someone yelling quotes from Joan Lindsay’s book. The rocks swallowed parts of the words and then, as I walked further, seemed to spit them back out.

Lindsay’s writing is enchanting, but contemporary readers might infer a disconcerting sense of terra nullius to the text. Claudia Rankine says in The Racial Imaginary that “imaginations are creatures as limited as we ourselves are. They are not some special, uninfiltrated realm that transcends the messy realities of our lives and minds.” It is clear that this historical novel is concerned with white history. There is no reference to the traditional owners, their long history and their forcible displacement from the area. The filmmakers put in an asphalt track when they were shooting Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock, but the rock has always had tracks.

Chapter 18, excised from Picnic at Hanging Rock before its publication, begins:

It is happening now. As it has been happening ever since Edith Horton ran stumbling and screaming towards the plain. As it will go on happening until the end of time. The scene is never varied by so much as the falling of a leaf or the flight of a bird. To the four people on the Rock it is always acted out in the tepid twilight of a present without a past. Their joys and agonies are forever new.

What better analogy is there for the eternal power of fiction? That long after the author has died, the world of a novel can live on in the imaginations of readers as they experience those events on the page for the first time. For a new reader and even for readers coming to read this book again, the characters’ “joys and agonies are forever new.” In these pages and in our imaginations, it’s still that “tepid twilight” when “Edith Horton ran stumbling and screaming towards the plain.”

The Secret of Hanging Rock, which includes this missing chapter, was published posthumously, as Lindsay always intended—or so said John Taylor, Lindsay’s original publisher and literary agent. Here we find answers of a sort to the mystery at the heart of Picnic at Hanging Rock. We discover why, a week after she went missing, Irma Leopold, the heiress with bouncing black curls, is found with bloodied fingers but “perfectly clean” bare feet that are “in no way scratched or bruised.” We see the manifestation of Lindsay’s obsession with time—it is said that she couldn’t wear a watch because they always stopped, as they do in the book. We see Miranda and Marion disappear. We see corsets hanging in midair. We see an ending as uncanny as Lindsay implies throughout Picnic at Hanging Rock.

There is a lot of play between the suppressed yet unbridled sexuality of these virginal girls. How powerful are they, so belittled, so underestimated. Through their actions they are able to change the very fabric of reality. They can strip themselves of the constraints of their society, their sex, but in the stripping there is only death. Yet it is a death that revibrates, that allows them to live on, forever stuck in that moment of lassitude, of high summer. ‘“Miranda,’ she called again. ‘Miranda!”’

When I last walked at Hanging Rock, I heard someone yelling quotes from Joan Lindsay’s book. The rocks swallowed parts of the words and then, as I walked further, seemed to spit them back out. The rocks themselves were damp and cold on the underside, licked by fern fronds. I tried to find the people calling, but couldn’t pinpoint where the sound was coming from. Giving up, I sat in the sunshine and looked out at the view, thinking not about the missing girls and governess at the heart of Picnic at Hanging Rock, but the peripheral characters whose stories are the actual meat of the book: Mrs. Appleyard, whose character darkens as the novel progresses; Sara, ill-fated Sara. I also thought about Terror Nullius, the work by video artists Soda Jerk (siblings Dominique and Dan Angeloro) that references Picnic at Hanging Rock, where Skippy speaks subtitled, postmodern jargon about how the mysteries of missing white people are privileged over the stories First Nation people tell.

I searched for the start of the track back down the hill and I came upon them: girls. They were laughing, calling to one another, their long hair caught by the wind, coats cracking in a gust. They were smiling, standing right up to the edge, where the monolith falls sharply to the plains. “Miranda,” they called and those girls looked powerful, vibrating with life, just on the brink of adulthood. They weren’t hot and dreamy. They didn’t have to disappear. They were electric.

______________________________________

From the introduction to Picnic at Hanging Rock, by Joan Lindsay, courtesy Text. Copyright Romy Ash, 2019.

Romy Ash

Romy Ash is a Melbourne-based writer. Her first novel Floundering was long-listed for the Miles Franklin Award. She is a writer of fiction and non-fiction. She has been anthologized in Best Australian Stories and Best Australian Essays.