On the Unlikely Origin of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time

Mark Haddon Recalls the Creative Process Behind His Stylistically Innovative Novel

I’ve been asked so many questions about writing Curious Incident over the intervening years that it’s now hard to excavate memories of the experience itself from memories of the answers I’ve given to those questions. What I do remember is this—having jumped ship from a literary agent who told me to concentrate on writing for children, I submitted the latest and least dreadful of my finished adult novels to Clare Alexander at Aitken Alexander. She told me she might be able to get it published but that she believed I could write something better.

At some point in the following months, at a loss for what this better novel might be and prompted by Sos to think about creating a compelling voice, I wrote three very different opening paragraphs, giving very little thought to what might happen next. The other two I’ve forgotten completely but one was a description of a dog lying on a front lawn with a garden fork thrust so far through it that it had entered the earth and remained upright. Sos was in the next room and remembers me laughing as I wrote this. I then realized that it would be funnier and more compelling if the narrating voice belonged to someone who did not think the scene was funny.

This chimed with something I’d written in a now-lost notebook wherein I’d glued a postcard of an Early Renaissance altarpiece triptych. I’d made a note beside it pondering how difficult it would be to explain the significance of this object—let alone its beauty—to someone who did not already share a huge number of cultural assumptions. The idea of someone with a Martian perspective was coming into focus, a perspective not unlike that of some of the people I’d worked with at the Actual Workshop and elsewhere—”Crown me, Mother, for I am to be Queen of the May…”—that of someone standing on the very edge or just outside what many of us lazily think of as our shared culture.

I remember with equal clarity and some shame that one of the many reasons for the dreadfulness of those unpublished novels was my need to prove to potential readers how clever I was. Worse even than poetry with a palpable design on us, as Keats didn’t quite say, is poetry that puts its hands in its breeches pockets and delivers a lecture in the expectation of applause. I should have gone cold turkey but I saw in Christopher Boone an opportunity to indulge my desire to pontificate by doing it in his voice. Rather than eliminating telling in favor of showing, I’d split them into two entirely separate strands.

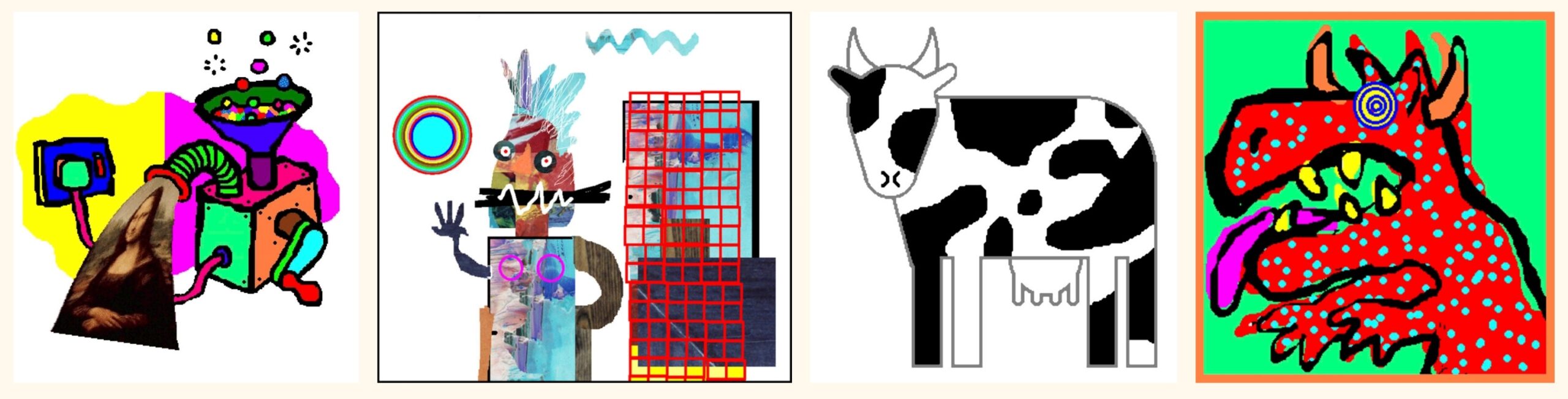

I remember, too, the serendipitous genesis of the illustrations in the book, all of them bitmaps created using the lo-res pixel-y Paint program that used to come bundled with Windows. I’d been fascinated by it ever since getting my first post-Amstrad computer. We take it for granted now but it was thrilling to be able to create digital pictures on a screen that could be edited repeatedly with no loss of quality and saved in separate versions for editing in different ways, all with the safety net of an undo button.

This was pre-stylus and pretrack-pad so the cursor had to be controlled with a mouse, a constraint which gave the pictures part of their character and charm. Sos mocked me for spending way too much time trying to master what seemed like a very niche skill. Then I realized who else would enjoy using the program and might turn to it as a way of helping illustrate their own story which didn’t depend on the English language with all its ambiguities and subtexts, how they might use those pictures to demonstrate to the reader the layout of Twycross Zoo or explain why the Milky Way, despite being a vast swirling disc, looks like a band of stars when seen from the Earth, or try to clarify the seeming paradox of the Monty Hall Problem.

__________________________________

From Leaving Home: A Memoir in Full Colour by Mark Haddon. Reprinted by permission of Doubleday, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2026 by Mark Haddon.

Mark Haddon

Mark Haddon is the author of the bestselling novels The Red House and A Spot of Bother. His novel The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time won the Whitbread Book of the Year Award and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for First Fiction and is the basis for the Tony Award–winning play. He is the author of a collection of poetry, The Talking Horse and the Sad Girl and the Village Under the Sea, has written and illustrated numerous children’s books, and has won awards for both his radio dramas and his television screenplays. He teaches creative writing for the Arvon Foundation and lives in Oxford, England.