On the Tricky Business of Creating a National Anthology: Irish Edition

Lucy Caldwell Reflects on What We Mean By a National Literature

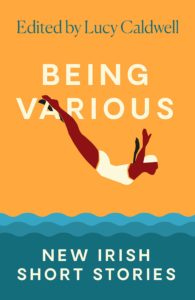

“I feel like a real Irish cailín,” tweeted the Chinese-born writer Yan Ge. A copy of Being Various: New Irish Short Stories had just arrived in the post and she’d seen that her story, “How I fell in love with the well-documented life of Alexander Whelan,” opens the anthology—which also contains work by the likes of Lisa McInerney, Sally Rooney and Eimear McBride.

When Yan Ge moved to Ireland in 2015, the first book she read was Town and Country: New Irish Short Stories, edited by Kevin Barry, a previous anthology in the Faber series. Now things had come full-circle. It was, she said, “magical.”

Melatu Uche Okorie, who came to Ireland from Nigeria as an asylum seeker, responded similarly to the news that her story, “BrownLady12345,” a subtle and nuanced account of a refugee exploring his sexuality, would be published in the anthology. “Would you believe,” she wrote in an email to me, “I have three editions of the Faber New Irish Short Stories series? And now I get a chance to be a part of it? This is MY Irish dream come true!”

Anthologies matter. Before I was a published writer, before I had started to consider myself an Irish writer, and long before I even dreamed of editing one of them, I too had the David Marcus-edited anthologies on my bookshelves. Whenever I’ve traveled to a new place, I’ve bought an anthology of that country’s literature. It might be the Dalkey Archive’s Best of Contemporary Mexican Fiction or Beirut 39: New Writing from the Arab World or Modern Greek Writing: an anthology in translation. Anthologies are an easy introduction to a place’s literature, and an instant snapshot of how that place sees itself. I have several anthologies of ghost stories, too, and love stories, always a sharp glimpse into the psyche of a particular time, and many anthologies of “young” or “emerging” writers.

The word anthology, first used in 1624, comes from the Greek word for flower, “anthos,” and “logia,” meaning to collect or gather. It’s a bouquet of flowers, an offering. Anthologies are a joy to read because of this delightful sense of variety: there’s always a story, a writer, a mood to suit the moment.

But the act of anthologizing is a deeply political one, too. The mid-century anthologies of Irish writing on my shelves invariably have only a handful of women writers, and usually the same three or four names. I have anthologies of contemporary Irish literature that do not include a single Northern writer. “New” is too often a synonym for “young.” And very few, even those that purport to be 21st-century collections, include work by Irish-born or currently-residing writers who have mixed cultural heritage.

As Linda Anderson and Dawn Sherratt-Bado, the editors of the recent Female Lines: New Writing by Women from Northern Ireland (New Island, 2017) say in their introduction: “There is a risk in the way that anthologies are seen as constructors of a canon. They can be used to cement existing hierarchies and unknown absences.”

The predecessor to their anthology, The Female Line, published by the Northern Ireland Women’s Rights Movement in 1985, came about when its editor, Ruth Hooley, lamented the lack of female writers on further and higher education course reading lists, or on the covers of locally-published fiction and poetry. She stated bluntly that her aim for the book was “to highlight what is being written and to encourage more women towards publication.”

Sinéad Gleeson, similarly, described her landmark 2015 New Island publication The Long Gaze Back: An Anthology of Irish Women Writers as an act of “literary archaeology”, seeking out writers who had all but vanished, and physically locating texts and work of a suitable length, in order to question and rebut the ways in which women writers are so frequently erased from the canon. Its publication spurred many conversations about whose stories are missing, not just from the literary pantheon, but our quotidian lives. It was at a panel discussion for The Long Gaze Back, at the Lyric Theatre in Belfast, that the four Northern women panelists remarked in incredulity how rare it was to share a stage, and agreed we needed our own anthology, and The Glass Shore: Short Stories by Women Writers from the North of Ireland was born.

A good anthology becomes more than the sum of its parts. The stories talk to each other: augment and contradict each other. As the editor, you try to curate the contents in ways that will allow for such conversations to occur. David Marcus saw the energy of his Faber series as coming from the juxtaposition of brand-new writers alongside established and lauded names, so that was my first guiding principle. My second was to focus on writers who began to publish after the Good Friday Agreement. It changed everything for my generation, and for the North, allowing us, for the first time, a plurality of identity; opening the way both practically and psychologically for a new sort of Irish identity. This seemed entirely in keeping with the Marcus spirit.

The final rule was that all work had to be brand new. That meant I commissioned writers, rather than selecting from stories already written, so I had little control over subject matter. But I knew from the start that I wanted a good representation of female writers, and writers from the North, and perhaps most importantly of all, of writers who might be Irish by dint of parentage or residence rather than birth.

I wanted, also, representatives of the sort of writing that’s all too often excluded from self-styled “literary” anthologies. Young Adult fiction is the place where some of the thorniest questions about feminism and bodily autonomy are being addressed, and where the frankest discussions about gender and sexuality take place. The importance of the crime-writing scene in the North, and the way it has confronted the political violence of the past, especially in the absence of a formal Truth and Reconciliation Commission, has long been under-, if not unacknowledged. It seemed crucial, too, at a time of rising right-wing rhetoric, when the mainstream media seems ever more intent on normalizing the ugliest types of nationalist and neo-fascist sentiment, to make a gesture of openness.

Being Various: New Irish Short Stories is a snapshot of where we are, now. It’s also a provocation: it asks, just as many of its individual stories do, again and again, questions about contemporary Irishness which cannot be answered, only further complicated. But most of all it’s a celebration—of the range of brilliant writers we have working today, and of the spirit of glorious multiplicity, taking its title from Louise MacNeice’s poem, “Snow,, and the lines that are the closest I have to an article of faith: “World is crazier and more of it than we think / Incorrigibly plural.” Long may that be the case. I pass on the torch.

_______________________________________

Excerpted from Being Various: New Irish Short Stories, edited by Lucy Caldwell. Used with permission of Faber & Faber. Introduction copyright © 2019 by Lucy Caldwell.