On the Self-Education of Frederick Douglass, Malcolm X, and the Insatiable Quest for Literacy

Brandon P. Fleming Recalls the Life-Changing Lessons of Undergrad

Crossing campus to DeMoss Hall, it felt like I was walking the green mile. A marble fountain guards the giant four-story edifice. Roman columns tower above an Olympian staircase ascending to an imposing entranceway. Once inside, it took me a minute to find the offices for the English and Modern Languages faculty, which were tucked away in a side hallway behind an anonymous double door. I walked the main hall of this building nearly every day, but I had never noticed the faculty offices. Nor had I ever looked at the wall of display cases filled with trophies or read the four words emblazoned above the exhibit: LIBERTY UNIVERSITY DEBATE CENTER. It meant nothing to me.

When Professor Nelson saw me at the open door of her office, she gestured toward a chair that was perhaps the only uncluttered surface in the room. Huge bookcases were crammed with shabby paperbacks and pristine hardbacks, and unsteady stacks of books rose from the floor like a city skyline. Her desk was littered with typewritten pages bleeding red ink, empty coffee mugs rested on stained napkins, and a formal, gold-framed portrait of what must have been her family looked disapprovingly down at the mess.

After I sat and shucked off my backpack, she reached into a laptop bag and extracted a sheaf of double-spaced pages with my name at the top. She slid the sheets toward me and let silence settle for a minute.

“Did you write this?” she asked. Her tone was calm, not accusatory, leaving the door open to candor. I considered my next lie, thumbing through the pages before nudging them back to a neutral position.

“Yes, ma’am,” I said.

Time froze as various scenarios played in my mind. She might pick up the essay and say, “Brandon, this is superb!” Or maybe she’d turn sarcastic and say, “You sure fooled me; there’s no way I could have ever detected that you stole this peer-reviewed essay from JSTOR.” But she did neither. Instead, she set the essay aside, as if it was not the most important matter. She looked calmly at me, her elbows resting on the desk and her fingers interlaced. She leaned forward and said, “I want to know more about you.”

Minutes passed and it was as though the essay was forgotten. She asked about my family, my aspirations, my struggles. Not as though she was interrogating me, but as though she cared to know. As we talked, my lie lingering unattended between us, I felt my wall of wariness begin to crack. But I didn’t recant.

In the course of an hour, we exchanged tears, laughter, and promises. She was vulnerable with me: she told me about having surgery for cancer. I was vulnerable with her: I told her about my history of drugs and violence. She made me feel safe. We laughed at stories about her childhood. I told her stories about my own. We went from chuckling to whooping with laughter, like old friends chatting under ideal circumstances.

It made sense to assume that I was stranded in my lonely foxhole, and that no reinforcements or rescue party would ever come.I never thought that I could bond with an older white woman. Then our conversation suddenly shifted. There was a natural pause in our exchange as she softly smiled at me like I was her own child. Then came the blindside hit.

“Brandon,” she said, “just tell me the truth.”

She’d tricked me. Soon as I had let her in. I should have seen this coming. My childhood, my secrets, her stories that she used like bait to draw me in—it was all a ploy to make me defenseless. I felt exposed, like I had been meat-checked by an old white lady. I was furious and glared at her across her trashy desk, my fingernails sinking into my palms as I clenched and unclenched my fists because I did not know what else to do.

“You can tell me,” she said, seemingly unaffected by the shift happening before her eyes, my anger falling apart into confusion and pain. Her steady gaze spoke volumes. “I’m not your enemy,” she added softly.

But I did not believe her. My view of the world was so fractured that everyone was my enemy, out to expose my vulnerability and fraudulence. It made sense to assume that I was stranded in my lonely foxhole, and that no reinforcements or rescue party would ever come.

“Fine,” I said angrily. “The truth is I can’t read this stuff.”

Faulkner, Homer, Dante—I didn’t understand a word of their books. I admitted to plagiarism. I admitted to cheating on the five-question quizzes. I admitted to being just as dumb as she and my classmates supposed. I admitted that I was one F or W away from flunking out of college for the second time. My voice rose and cracked with stress and hopelessness. And when I wound down—before I could bolt from the room—she rose from her chair. She walked over to me. She wrapped her frail arms around my body and promised me that I was safe. I closed my eyes, and I rested my head on her shoulder as her empathy calmed my spirit.

“I understand if you have to fail me,” I said, head sunken.

“I’m not going to fail you,” she said, refusing to accept my surrender. “We are going to redo it.”

I didn’t understand what she meant by “we.” In this instance, simply allowing me to redo it would be an act of grace. But when I explained that English was too hard, that I wasn’t cut out for it because I was so many miles behind everyone else, she wouldn’t allow me to wallow in self-pity. She told me that I was not in it alone. She was willing to get down into the trenches and struggle with me until I figured it out. She went beyond the call of duty for me.

Over the next several months, she spent weekends and time outside of her office hours to help teach me how to read and write. But the way she did it was, perhaps, the most impactful. She met me where I was, as a Black man. She talked about two other Black men who’d charted their own journeys to literacy. Their names are Frederick Douglass and Malcolm X. But I brushed aside these well-meaning comparisons, certain that my deficiencies were far worse than any shortcomings these men ever had. But she did not enable my self-pity. I saw everything that I wasn’t. But she saw everything that I had the potential to be.

“You have two decisions you can make,” she said to me one day. “You can moan about your disadvantages, or you can do something about them. The choice is yours.”

Suddenly, it struck me that I had been here before—not as a student, but as an athlete. When I was in middle school, I realized that I was not going to grow tall. I was fast, I was strong, I was skilled, but I was short. Yet as an eighth grader, I was recruited to play on the high school level of the Amateur Athletic Union, a national league for elite travel basketball. I’d send defenders crawling on the floor with swift crossovers, plow through the lane with agility, and spring in the air for a layup—only to have my shot deflected to the rafters by a six-foot-something giant who would stare me down as the crowd cheered. My confidence about my skill was undermined by worries about my height. I concluded that I was out of my league.

But Coach would have none of that. With a piece of gum flapping in the corner of his mouth, he’d step to my face and in his drill sergeant voice say, “We don’t complain, son. We compensate.” Excuses weren’t allowed. And if I, or any of us, ever tried to use them—it didn’t matter what point of practice we were in—he’d halt and roar, “You makin’ excuses, boy?” Then the whistle would blow as he screamed, “Assume the position!”

Fifteen wheezing bodies would hit the floor and, while doing push-ups, we’d chant in chorus: “Excuses are tools of incompetence, which build monuments of nothingness. And those who specialize in them seldom specialize in anything else.”

So I’d stopped making excuses on the court and invested in a pair of strength shoes, training sneakers with a platform in the front that forces your calf muscles to bear the strain of keeping your heels elevated. For an entire year, I spent hours in my garage—mornings, after school, weekends—jumping rope and doing plyometric training. By the time I reached the ninth grade, I could soar above the rim—dunking and jumping higher than most guys who were older and taller than me. It was this discipline—and the intense labor—that allowed me to play much taller than I was.

I realized that Coach and Professor Nelson were sending me the same message. There was probably no academic equivalent of strength shoes, but I wanted to know more about the two Black men she had mentioned. Of course, I’d heard their names before, thanks to dutiful Black history programming in school every February. Those learning modules were meant to engender respect for Black history, but they actually oversimplified and diminished it. Douglass was famous as an abolitionist and the sainted Black friend of Abraham Lincoln, but I knew nothing of him as a self-taught scholar and rhetorician. And when our textbooks or teachers made any mention of Malcolm X, he was positioned as the violent antithesis to Dr. King—not celebrated as a revolutionary and an autodidact.

I purchased the two books. I struggled to read them and it took a long time. My eyes watered, I fell asleep often, and I gave up several times. Not because I was uninterested. I was not conditioned to sit and read for extended periods. I spent more time looking up words than actually reading the books. I read through entire paragraphs and pages, then had to go back and read them again for understanding. It was tough, but there was something new and unusual pushing me through. As I read deeper, I was lost in the best way. And I was found in the same way. The feeling was euphoric, and foreign. Eventually, I finished. And it all made sense. If they could rise above their disadvantages to become scholars, there was no excuse for me.

Douglass was an illiterate slave. Malcolm was a dope-dealing gangster. Douglass had a teacher who barely taught him phonetics, and he took it upon himself to become a voracious and critical reader. Malcolm went to prison, and his journey to literacy began with his decision to copy thousands of words and definitions from the dictionary. They were me. I, too, was enslaved by ignorance. I, too, wanted to be delivered from the prison of my inferiority. I, too, felt the nakedness of being unlearned.

Rage mounted in me as I devoured these books. A certain fire is sparked when you realize that you’ve been deceived. All my life I’d believed that Black scholars didn’t exist. Maybe they existed somewhere in the world, but not in mine. They weren’t in my neighborhoods. They weren’t on my television. They weren’t in the textbooks that teachers wanted me to read. All I saw was Black gangstas and Black drug dealers and Black athletes. So that’s what I wanted to be, because that’s what I thought Black people did. Representation is the lens through which we aspire.

I saw Allen Iverson—with his cornrows and tattoos and urban swag—and I thought I could be him, because he looked like me. Sure, I had heard that only three of every 10,000 high school players ever make it to the NBA. But representation impacted me more than probability. When I saw Iverson, Stephon Marbury, and Vince Carter, I saw myself. And that was all that mattered for a kid who was learning how to dream.

Why is it that basketball was all I ever wanted? It’s because passion is born through exposure and affirmation. My mother had put a ball in my hands. She’d showed me what to do with it. Then she’d told me that I was good. But what if someone had put a book in my hands instead of a ball? What if someone had showed me how to read and then told me that I was smart? What if that book had exposed me to something great about my people and my identity that I could be proud of? What if it had showed that I was a part of a rich legacy of greatness? What if it had exposed me to my heritage and native land in a way that did not depict Africa as the quintessence of poverty? What if it had showed me something about my culture that is inspiring, not injurious, and that did not pretend that Black history began with slavery, or that did not relegate Black achievement to a 400-year freedom struggle?

As I kept on reading, I soon realized that history is told by the victor. Told from the perspective of the person who wields the pen like a spoil of war. And the oppressed are left with a narrow study of their own defeat, left out of the story or indoctrinated with the fiction of inferiority. My life would have been completely different had I known these truths. But I knew them now. And I was ready to do the work of undoing my own miseducation.

__________________________________

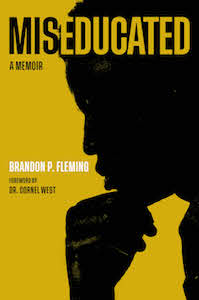

Excerpted from MISEDUCATED: A Memoir by Brandon Fleming. Copyright © 2021. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.