On the “Secret” Wedding of Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier

Or, When the Prude, the Filmmaker, and the Lovers Roadtripped to Santa Barbara

A year after Vivien Leigh had landed the role of Scarlett O’Hara in 1939’s Gone With the Wind — and only a little longer since Laurence Olivier had been cast as Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights—the two were global superstars. Now the lovers, still unmarried—and yet to be divorced from their previous spouses—had to decide what to do next.

This was the right time, director George Cukor advised Vivien and Larry, to cash in. They were universally admired, even held on a pedestal, despite their illicit union. Around the country, hordes of people would surely flock to anything they did onstage. And so they made their biggest error to date with a nationwide tour.

Rather than choose something simple or even a manageable contemporary work, Larry selected the one play in which he had most conspicuously failed: Romeo and Juliet. The last time he had tackled Shakespeare’s tragedy, in his joint production with John Gielgud, he had been slammed for mangling its language, for essaying a Romeo who was all fire and no finesse. And yet he was determined to do it again.

Call it foolish (as many did), the effort nonetheless revealed a side of Olivier that was only now beginning to flower: a willingness to try and try again, no matter how great the odds—not simply to sidestep his past mistakes but to confront them head-on. That intellectual and artistic courage became one of his defining traits, most apparent when he returned to the title roles in Othello and Macbeth, two notable flops at the Old Vic that he would make memorable hits.

As he began a new film of Pride and Prejudice, costarring his former lover, Greer Garson, he used every spare minute to study the text, reading and rereading the play during his breaks. He turned to his director, Cukor, for counsel, perhaps not the wisest move given that Cukor had shot a lumbering 1936 adaptation of Romeo and Juliet that Larry had turned down. At the same time, he immersed himself in every detail of lighting and staging, planning to direct this production as well as play the lead.

But when the show opened in April 1940 at San Francisco’s cavernous Geary Theater, it was a flop. His Romeo was hardly any different from the Romeo he had played before—a “roaring boy,” as cast member Jack Merivale described him (though at 33 years old, he was a little old to play a boy). Vivien’s Juliet fared somewhat better, conceived with Larry’s guidance as a young girl barely into her teens, but she lacked the vocal projection to reach the back of the theater.

On opening night, Larry was so exhausted that when he attempted to vault up a wall to Juliet’s balcony, he fell short and was left clinging by his fingertips, provoking peals of laughter.

From San Francisco, the company traveled to Chicago and then to New York’s Fifty-First Street Theatre, where any hope of success was killed by the sweltering heat. Audiences in the unairconditioned auditorium dripped with sweat, just like the actors, and Olivier, wrapped in thick clothes and squeezed into a tight corset meant to contain an incipient paunch, was horrified when his putty nose began to melt. “The stage was like an oven,” he wrote. “I was drenched.”

The production, wrote Time magazine, was “not merely weak or spotty, but calamitous. [The audience] saw a Juliet who looked like a poem, but had no sense of poetry, a Romeo who made a handsome lover, but talked as though he was brushing his teeth, conducted his courtship as though he was D’Artagnan. They saw fear and grief portrayed by belly-writhings and animal howls. They saw Olivier, in the first balcony scene, rush around like a dazed fireman trying to save a trapped maiden from the flames.”

It was against this backdrop, as the Nazi threat drew ever closer to their homeland, that Vivien and Larry decided to get married.

When a crowd gathered to demand its money back, Larry stormed outside, where he proceeded to distribute wads of cash, promising a refund for anyone who wanted it. Too many did and the show ground to a halt in June, a month after its Broadway premiere, costing the couple all their savings: $96,000. “For sheer, savage, merciless cruelty,” he said later, exaggerating the disapprobation he felt on all sides, “I have never seen any judgments to approach those that faced me at breakfast in our New York hotel.” He had lost everything: his money, his pride, and his reputation. Even worse, he had lost his supremacy in Vivien’s judgment, at least in his own mind.

Always more sensitive to slights than Vivien (she had a gift for turning enemies into friends and making her harshest critics her allies), he began to perceive adversaries all around, nitpickers finding fault with everything he did. This was more paranoia than reality, but it was also deflection, designed to disguise the truth he couldn’t bear: that he had let Vivien down.

Vivien herself was sick with disappointment and begged her castmate, Merivale, to come over and restore her and Larry’s spirits. He found them “drowning themselves in lethally strong Martinis” and in a foul mood, writes one of Olivier’s biographers, Anthony Holden. When Merivale beat Vivien at checkers, “she threw a tantrum and accused him of cheating, screaming for Olivier to come and intervene.” Her words were revealing: “Don’t you try to come between us,” she yelled. “We’ve been together for years. Nobody’s coming between us. Don’t you try!”

The day after Romeo opened in New York, on May 10, 1940, an ascendant Germany attacked Belgium, France, and the Netherlands in a massive land and air assault that overwhelmed its flabbergasted enemies. As Allied forces tried to repel the invasion, 136 divisions stormed their frontiers, backed by 2,500 planes and 16,000 airborne troops, dropping in swarms from the fighter-thickened skies. German tanks quickly penetrated the French defense and continued to the Atlantic coast, where within a month the “Boche” had trapped 300,000 French and British soldiers on the beaches of Dunkirk.

It was against this backdrop, as the Nazi threat drew ever closer to their homeland, with no guarantee the country would survive, that Vivien and Larry decided to get married.

Vivien’s husband, Leigh Holman, and Larry’s wife, Jill Esmond, had finally conceded and the divorce papers had come through, freeing their former partners. And so, back in Los Angeles after their tour, late on August 31, 1940, they set out for Santa Barbara, joined by their friends Katharine Hepburn and Garson Kanin, the writer of Born Yesterday. They could not have picked a more idyllic venue—one of the prettiest parts of the state, overlooking the untarnished Pacific coastline, among gentle bluffs covered with ancient pines, where the sound of waves was broken only by the cries of gulls. But the wedding was a shambles, if one is to believe Kanin, who described it gleefully, though quite waspishly, in his 1971 book Tracy and Hepburn: An Intimate Memoir.

They stayed glued to the radio, waiting for word to leak about their “secret” wedding, only to be sorely disappointed when it didn’t.

According to Kanin, he had just left the Beverly Hills house he was nominally sharing with Olivier to visit Hepburn, hoping she would agree to star in a new movie about the wife of Ulysses Grant (in which Grant would never appear), when Larry called him in a panic. He was getting married that night, he revealed, and wanted Kanin to be his best man. Enlisting Hepburn as the maid of honor, the group set off on the long and winding 90-mile road to Santa Barbara, with Larry at the wheel and Vivien at his side. The lovebirds quarreled incessantly. “It was absolutely hilarious,” writes Kanin. “She was sharp-tongued, Larry was tough as hell. They were scrapping all the way to the banns.”

Hepburn recalled things rather differently. “At that time, I really didn’t know Vivien or Larry well,” she said. “Vivien led the social whirl kind of life that was anathema to me. But Gar Kanin and I sat in the back seat of Larry’s Packard and Larry drove and, of course, Vivien sat close to him in the front seat. I remember feeling the conversation she and Larry were having as we drove along was, well, rather racy. But this was probably the prudish reaction of a girl like myself who had been sheltered from the great world.”

The prude, the filmmaker, and the lovers arrived that evening at the San Ysidro Ranch, a hotel partly owned by Ronald Colman, who was waiting with his wife, Benita, and a justice of the peace. The justice had been cooling his heels for an hour and a half, recalled Kanin, and had to be plied with drink just to stay and wait; by the time the couple arrived, he was so drunk that he kept calling Larry “Oliver” and Vivien “Lay.” “Larry was asked if he took this woman to be his lawful-wedded wife,” writes Kanin, “but [the official] forgot to ask Vivien for her vow, and me for the ring, although I kept waving it under his nose.” (With mischievous humor, Larry had gotten the ring inscribed, “The last one you’ll get, I hope.” Vivien had chosen something more earnest: “La fidélité ma guide”—faithfulness is my guide—a less-than-subtle hint.) “Finally,” continues Kanin, “there was a long pause and a silence, broken only by a few chirping crickets and my continuing sneezes [from allergies]. The justice of the peace, weaving slightly, looked up and shouted, ‘Bingo!’” That account puzzled Hepburn, who later had “no recollection of anyone calling out ‘Bingo!’ It would seem to me a very odd thing to do.”

Afterward, the married couple drove back to Los Angeles and on to the port of San Pedro, where they took Colman’s yacht to Catalina and stayed glued to the radio, waiting for word to leak about their “secret” wedding, only to be sorely disappointed when it didn’t. At ten o’clock the news broke.

“Too bad it got out,” said a joyful Olivier. “Yes,” sighed a happy Vivien.

______________________________

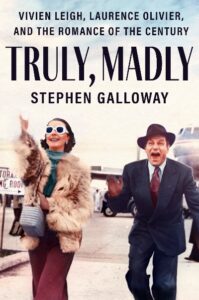

Excerpted from the book Truly, Madly: Vivien Leigh, Laurence Olivier, and the Romance of the Century by Stephen Galloway. Copyright © 2022 by Stephen Galloway. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Stephen Galloway

After many years as the executive editor of The Hollywood Reporter, Stephen Galloway was recently named the dean of Chapman University’s Dodge College of Film and Media Arts. An Emmy Award-winning writer, Galloway created the Reporter’s celebrated Oscar Roundtables, along with the Netflix series The Hollywood Masters, which he hosted and executive produced. Over three decades, he has written about a who’s who of Hollywood and the media, from Steven Spielberg to Meryl Streep, from Ted Turner to Tom Cruise. He is also the author of the bestseller Leading Lady: Sherry Lansing and the Making of a Hollywood Groundbreaker.