On the School-to-Prison Pipeline, and Being Unable to Protect Those You Love

Melissa Valentine Reads a Letter From Prison

Poof. He’s gone.

You can live on a hill. You can live on the good side of town. You can live among white people. You can even have white relatives. You can leave. You can return. You can have opportunity. You can be loved. But you will still be vulnerable.

My brother is in prison, along with too many other black men. The street I didn’t want to see is now illuminated. There is a funnel that begins at birth, it begins when you are first labeled bad, a degrading pipeline through school and all the way into a hopeless future. Junior has made it through to the end of the tunnel. He is in good company with his brothers, each with different stories of desire and hunger, all distorted and gone awry, each a human and a monster, fully grown now. He’s become a monster now— 18 years old, a man.

There is a new silence that rings through the house in his absence. It’s piercing like a siren whose call you can still hear after it’s long gone. We must catch our breath and ease it back to a normal rhythm, whatever normal is, and occupy the hours and minutes and seconds that were filled with worry and dread. Some sort of PTSD daze comes over us, especially Mom and Dad, who look ill. Which is worse, prison or the street? Knowing or not knowing? I go on with my days, entrenched in a new kind of denial. He’ll be out soon, they’ll reduce his sentence, when he’s out he’ll be reformed, he’ll get a job and go to college. He is different from the rest—I believe somehow our love makes him different. But this is not what happens when you go to prison.

He said he couldn’t be caught. He lied. He lost. This is the biggest loss yet. It can’t be good in there, I think to myself, not wanting to believe the reality, whispering, “Do better, do better,” to an empty house, his empty room. I am angry with him for not being invincible, for losing. All those secrets I kept. All the things I witnessed. I was a good accomplice, a good witness. I was a good sister. All of it was my investment in some future I imagined for us. Some future where we could be free and happy, where we could have what we wanted, where we could exist without protection, where the possibilities for who we could become would be endless. I try and hold on to my denial, this idea that he is different, the idea that maybe he’ll change, but his being in prison is evidence against this vision. His being in prison is proof that we are losing this game. Hope is not enough. This hopelessness begins to creep into my very being.

He is different from the rest—I believe somehow our love makes him different.

This special sight his story has given me is a superpower I don’t want. My special ability to see humans in monsters, my belief in monsters, my love for monsters, and now the certainty that aligning with monsters makes me on the losing side. It’s mine now and all of ours—this knowing that there is a design for our destruction. I become this knowing. It is in my cells. My brother being in prison now lives in my cells. We couldn’t keep him away from the street. We couldn’t protect him. We are all losers. I try and push away the feeling of abandonment that threatens to show and keeps me from visiting him. We don’t know how long it’ll be. There was jail and now there are courts and prison and soon there will be a different prison, one much farther away from us where they will hold him until his hearing, where he’ll finish out his sentence. California is full of prisons. He is just one out of millions.

A letter addressed to me has been slid under my bedroom door. In the return address corner is Junior’s real name, Christopher Valentine, followed by a long number. His handwriting is of the precise, practiced sort that has never written much except from prison, as if his life depends on it. It is now the only way he can express himself. For many days I do not touch it. It lies on the floor in the heap of my teenage life: graded papers, torn-out sheets of glossy magazine pages, photos taken with friends, books, clothes.

He mostly writes to Mom and Dad, promising things that make them boast for a week, that he’ll get his GED in prison, that he’s reading one of the books Dad sent, that he plans to go to college when he gets out, before they go back to their ill state, the state you exist in when your child is in prison. But one day there is a letter with my name on it. I crank open my bedroom window and step out onto the roof. With a cigarette, a lighter, and the letter, I sit on the warm shingles and stare out over the neighborhood into a sea of rooftops and trees. I light up a Marlboro Red and look at the stick figure drawing he’s included in the margin of the thin paper. A boy behind bars with the caption: I want to come home.

Seeing it melts my angry facade. I’m angry because we lost. I’m angry because we failed. I’m overwhelmed by this. We couldn’t keep him safe. I’m angry because I can’t unknow what I now know about the world and what it does to my brothers. I’m angry because I’m a teenager. I’m angry because I’m alone and undirected. Who can I trust to show me what I can be? Who will show me how to be? I stew inside these questions; I’m intimate with them. I let them inside my body through cigarette and marijuana smoke, alcohol, razor blades, whatever destructive thing I can find. I ask cigarettes and weed and alcohol if they know the answers. And my anger is also simple: I miss my brother.

Dear Melissa,

What’s happening with you? Do you like Tech? You better be going to all your classes and doing good in all of them. If I could have the chance to do everything over, I’d probably be in college right now, but instead I’m in San Quentin. Who knows where they’ll end up moving me. Everybody used to say if I ever ended up in jail or prison, I’d end up being somebody’s bitch. I’ll be damned if that happens. Look at this shit, I know this should have been two or three paragraphs, but I don’t know how to do that shit. I know you’re not a boy and wouldn’t do half the things I’ve done. But look at me and ask yourself, is this any kind of a life? It may look good on the outside, but I’ll tell you. It feels like shit on the inside.

I look out above the trees, numb. This is my spot. On the roof I can think, just be. I can taste what it might feel like to exist apart from my family, outside of this house, outside of the way I feel. Prison produces a different kind of death. It is an insidious, poisonous kind of death that kills not only the prisoner but the family too, especially the parents, especially if the prisoner is eighteen and mostly a child. I take another drag from my cigarette and continue.

Mom and Dad don’t know what to say about me. I don’t either. I feel discouraged to try and go to community college. Look at me. One big ass paragraph. I can’t even write a letter let alone get past ninth grade algebra. There’s a reason for everything, but for a person who always has a reason or excuse for everything, it gets old. This shit in here is degrading—taking showers with thirty other boys. There isn’t much a person could do or say to make me feel worse than I do, ’cause there aren’t too many things worse than being in prison. I can’t think of many words to tell Mom and Dad except I’ll be home soon.

For a few more lines he scolds me for doing poorly in school. Not seeing any irony in doing so, he demands I improve my GPA. He has heard I’m not doing well. He bribes me, tell- ing me he’ll buy me my first car when he gets out, a Lexus. Love, Jr., he signs off. My cigarette burns away between my fingers. I take in the last drag of smoke and toss the butt onto the neighbor’s ivy-covered roof. I throw the letter back inside my room, onto the floor, and stare out above the roof-tops. I trace them all the way up to the cemetery at the top of the hill where our street ends and meets the dead—one line, one tiny speck of map that expands and expands and expands until I see just how nothing we are, how nowhere. The absence of Junior takes the life from me.

__________________________________

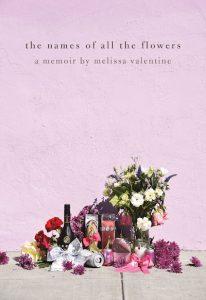

Excerpted from The Names of All the Flowers by Melissa Valentine. Copyright © 2020. Reprinted with permission from the Feminist Press

Melissa Valentine

Melissa Valentine is a writer from Oakland, CA. She earned her BA from Sarah Lawrence College and her MFA in creative writing from Mills College. She has been a fellow at the San Francisco Writers' Grotto, and her work has appeared in Jezebel, Guernica, Apogee Journal, and others. Her writing has received honorable mention from Glimmer Train and the Ardella Mills Non-fiction Award. She currently lives in Brooklyn, NY.