On the Role of Black Women in the Struggle for Suffrage

Kate Clarke Lemay Curates 'Portraits of Persistence' at the National Portrait Gallery

To mark the centennial of the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment in the Senate on June 4, 1919, National Portrait Gallery historian Kate Clarke Lemay reflects on curating the exhibition “Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence.”

*

In curating “Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence,” the exhibition on view at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, I worked at the sometimes tenuous intersection of scholarship and object collections. The narrative of any exhibition is always driven by the archive, and in this case it depended on whose portrait I could find, which visual culture enabled a deeper dive into the history, and whether or not these objects were appropriate for display in an art museum (which requires them to be original, vintage, and in good condition).

This can be problematic. I recall the crushing disappointment I experienced, for example, when I traveled to New York City to see a photographic portrait of Josephine St. Ruffin (1842-1924), only to find out that it had a large, demeaning and ruining crease down her face. I desperately wanted to feature Ruffin, a Boston suffragist, clubwoman and editor of the African American newspaper The Woman’s Era, in the exhibition. But because there were no good portraits that I could find, I had to settle for picturing her in the catalog, only.

Fannie Lou Hamer by Charmian Reading. Gelatin silver print, 1966. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. © Family of Charmian Reading.

Fannie Lou Hamer by Charmian Reading. Gelatin silver print, 1966. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. © Family of Charmian Reading.

In total, I found 50 portraits of named women, and created context around them by including 74 more objects like genre paintings, textiles, videos, posters, ephemera, material culture like china, and first edition publications authored by women. I felt charged with the responsibility to change the narrative about American suffrage history and make it more inclusive. Thirty-two percent of the portraits in the exhibition are of women of color. As a result, the exhibition’s narrative is different than those that typically focus on suffrage. African American women were intersectional in their approach to suffrage—rather than taking on a single-issue—and so the exhibition presents a larger picture of black women’s activism. By featuring portraits of the formidable diplomat, Ida Gibbs Hunt (1862-1957), I was able to include the story of how she brought women’s equality to a pan-African reach.

With the portrait of Margaret Murray Washington (1865-1925), who was a clubwoman and the “Lady Principal” of Tuskegee University, I found a way to point to the different tactics women used to achieve equality. At Tuskegee, Washington (and her husband, Booker T.) emphasized traditional women’s roles, like sewing and laundering, that would offer employment in trade. Choosing to be more inclusive also meant featuring photographs like daguerreotypes and works on paper, rather than oil paintings. In the end, I selected portraits of suffragists in the medium of photographs and frontispieces. This allowed me to create a sense of equality by avoiding the hierarchy read through the value of an object and its medium.

Susette LaFlesche Tibbles by Jose Maria Mora. c. 1879. Albumen silver print.

Susette LaFlesche Tibbles by Jose Maria Mora. c. 1879. Albumen silver print.National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

I proposed this exhibition about women’s suffrage in late 2015, as I was thinking ahead, already, to the 2020 centennial anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was a complicated history to think through, especially as the 19th Amendment never actually guaranteed women the right to vote. As I worked through the problems of the exhibition, I came to understand that American women’s suffrage history is as much a study of the Constitution and the political machine as it is a long social history featuring the activism of largely forgotten women.

Few scholarly books present the national strategy of state referendums in a way that is legible to people unfamiliar with how our government really works. Analysis of the federal government is murky at best. The social reactions of the South to 14th and 15th Amendments, and their direct relationship to that of the 19th, is also misunderstood. Most Americans in the late 1860s and 1870s thought the idea of universal suffrage was unrealistic. Nevertheless, in an uncharacteristic turn towards serious consideration of the political event, in this drawing for Harper’s Weekly, the caricaturist Thomas Nast naively (or perhaps, hopefully?) praised the 15th Amendment as creating equal suffrage for everyone.

I came to understand that American women’s suffrage history is as much a study of the political machine as it is a social history featuring the activism of largely forgotten women.

Race relations, the threat of the enfranchisement of black women, period prejudice and pragmatism, southern sovereignty versus the federal government, defensive reactions to Reconstruction—all these things fed the anti-suffrage machine. The attentive visitor to the exhibition will make important connections between this history and present-day voter suppression, including the reduction of the number of polling places in regions heavily populated by African Americans, the requirement of identification cards, and in North Dakota, the efforts to disenfranchise Native Americans by requiring a physical address in order to register to vote.

Felisa Rincón de Gautier by Antonio Martorell. Charcoal on paper, 1992. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution/©1991 Antonio Martorell.

Felisa Rincón de Gautier by Antonio Martorell. Charcoal on paper, 1992. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution/©1991 Antonio Martorell.

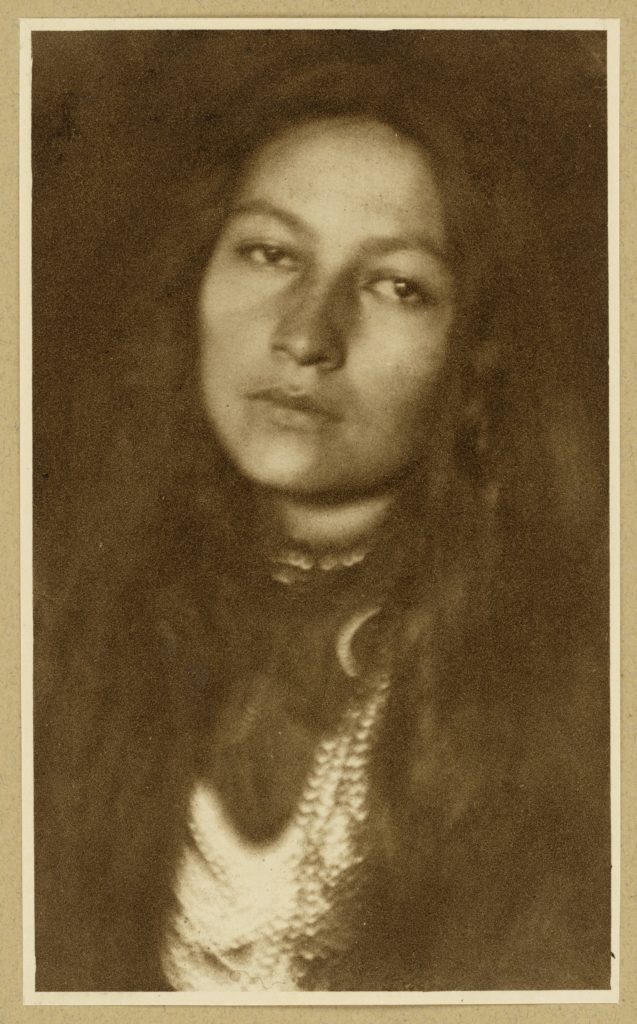

Indeed, women’s citizenship rights and its history is not only about one issue—suffrage—but also about the fight for sustained access to schools, public spaces, financial institutions and organizations. For example, Anna Julia Cooper was long at work to give black high school students a college preparatory education—she was one of the first teachers at the M Street Colored High School, now Dunbar High School, in Washington D.C. African Americans were not the only group who faced systemic denials to citizenship rights; Asian American women had a long battle to equality, as well, as pointed to by the exhibition’s inclusion of a portrait of Patsy Takemoto Mink. The way in which we approach suffrage history must include the ways in which Native American women such as Susette La Flesche Tibbles and Zitkala Sa; Puerto Ricans including Felisa Rincon de Gautier and Luisa Capetillo—as well as African American leaders who carried the suffrage cause right up to the 1965 Voting Rights Act, like Fannie Lou Hamer.

Zitkala-sa by Joseph T. Keiley. Photogravure, 1898 (printed 1901). National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Zitkala-sa by Joseph T. Keiley. Photogravure, 1898 (printed 1901). National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence is accompanied by a catalog of the same name, published by Princeton University Press. This important book features scholarship by experts Lisa Tetrault, Martha S. Jones and Susan Goodier; it is among the first to address the role of visual culture in the suffrage movement. Astonishingly, it is the first publication to present suffrage history in one broad stroke, linking American women’s history from the 1830s all the way up through 1965.

Anna Julia Haywood (Cooper) by H.M. Platt.

Anna Julia Haywood (Cooper) by H.M. Platt.Albumen silver print, 1884. Courtesy of the Oberlin College Archives

The book analyzes militant suffragists and the visual culture they used, including maps, banners, material culture like china sets, and posters. The book also presents fragile objects that I could not feature in the exhibition, including the original Benjamin Dale gouache (a type of watercolor), from which the official program was made for the 1913 suffrage parade. I suspect that it was the 1913 parade’s Grand Marshal, the artist May Jane Walker Burleson, who took the original home with her to Galveston, Texas.

Ida A. Gibbs Hunt by H.M. Platt. Albumen silver print, 1884. Courtesy of the Oberlin College Archives

Ida A. Gibbs Hunt by H.M. Platt. Albumen silver print, 1884. Courtesy of the Oberlin College Archives

I hope scholars might be encouraged to pursue new directions in scholarship on the topic. For example, the exhibition, the journalists at the Pudding.cool analyzed the ways in which women’s political voice affected party platform texts from 1840-2016, and political scientists Christina Wolbrecht and Dawn Teele have authored wonderful work about women’s political influence in the United States. But, what about the relationship between British suffragette visual culture, and that of American suffrage? Very few have teased out their relationship, whose intersection and exchange is prime material for important study. The role of black suffragists is beginning to be explored in depth by scholars like Martha S. Jones, with Rosalyn Terborg-Penn’s crucial scholarship as its base.

I hope that this exhibition engages the public through its stunning visual materials and fascinating biographies of American women in ways that express how central women’s history is to American history. The exhibition helped to publicly kick off #BecauseOfHerStory, the American Women’s History Initiative, which features a five-year symposia program, countless exhibitions organized across Smithsonian units, and a groundbreaking digital initiative. Visiting “Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence” may be one of the first experiences museum visitors have to be surrounded, literally, by women via their portraits of women and research about their biographies. The exhibition is a milestone marking the long continuum in the effort at the Smithsonian to explore American women’s history.

__________________________________

Votes for Women by Kate Lemay is out now via Princeton University Press.

Kate Lemay

Kate Clarke Lemay is a historian at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery where she directs its scholarly center, PORTAL. She earned a dual PhD in art history and American studies from Indiana University, Bloomington. Her book, Triumph of the Dead: American WWII Cemeteries, Monuments and Diplomacy in France received the 2018 Terra Foundation in American Art Publication Award. Its research was supported by an IIE Fulbright Award to France, a Smithsonian American Art Predoctoral Grant, and a postdoctoral fellowship at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum’s scholarly center. Dr. Lemay recently edited the special issue of the International Journal of Military History and Historiography on the topic of war cemeteries, and she has published essays with The Journal of War and Culture Studies, the University of North Texas Press and the Marine Corps History Division. She is the curator of “Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence” and the editor and coauthor of its scholarly catalog. Lemay is the co-coordinating curator of the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative.