On the Rise of the Vietnamese Noodle Shop in

Anchorage, Alaska

How Did Pho Come to Dominate in the Far North?

First, eat the pho with your eyes, Tony Chheum told me, when I interviewed him in 2014. Your big, round bowl should be volcanically hot, sending off curls of steam. Next to it, a pile of crisp mung bean sprouts, fresh basil leaves, cilantro sprigs, jalapeño slices, and a wedge of lime awaits. Next to that, if you want, a small platter of thinly cut, extra rare beef.

I was speaking with him in his restaurant, Phonatik, on Dimond. He was sitting across from me at a table in the VIP room, where the graffiti-style artwork on the walls matches his tattoos. I was there to talk about the Vietnamese noodle shops that had been colonizing Anchorage’s strip malls. Drive down any major artery in Anchorage, and a pho shop will eventually appear, tucked in next to a cell phone store or a manicure salon or a dry cleaner.

Pho Bowl, Pho 2000, Pho & Grill, Pho Tommy, Pho Jula, Pho Saigon, Pho Vietnams, numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and 8. As of winter 2018, there were 17 restaurants in Anchorage with the word pho in the name, according to state business licenses.

That’s only a sample. It doesn’t include Ray’s Place in Spenard or any number of Thai restaurants that also serve the noodle soup. You can even get pho in the cafeteria at Providence Alaska Medical Center. The noodle business is deeply competitive. That means pho-eaters have lots of delicious choices, but you have to know what to look for. (Before we go much further, a note on pronunciation: pho is pronounced like the first syllable in “fanatic.” It does not rhyme with “bro.”)

Pho done right is built on a broth made from slow-simmered bones.

Phonatik’s Tony Chheum, who was 29 when I interviewed him, is a former mechanic from Sacramento, third child of Chinese and Cambodian parents, who grew up working in his family’s doughnut shop. Restaurants are in his blood (his sister ran Alaska Bagel Restaurant), and pho, once his favorite hangover food, has been his all-consuming project for the last few years.

With the help of his girlfriend, Kimtra Nguyen, and her father, Bung Nguyen, both Vietnamese, he perfected his recipe. His business plan is all about introducing the food to newcomers. He offers first-timers a tableside mini pho-orientation he calls “Pho 101.” He took me through it.

“Next,” he told me, “eat with your nose. How does it smell?”

Pho done right is built on a broth made from slow-simmered bones. A good bowl should smell herbal, like ginger and star anise layered atop a formidable, beefy aroma. Chheum’s broth-making process takes 48 hours, he said. He won’t talk about the specifics. Few pho-makers do. (Tip: If you have MSG issues, always ask.) A good broth stands on its own, he said. Always taste the broth before adding anything to the bowl.

“A broth should be clean,” he said. “It should taste clean. It should be nice and dark.”

The noodle soup−selling business is so competitive in Anchorage that every shop has to work to stand out and cultivate regulars. Phonatik holds quarterly soup-eating contests, called “pho challenges,” where competitors have thirty minutes to eat as much as they can from eight-pound bowls of noodles, broth, and meat. I went to a ten-way challenge a few months before the interview. The rowdy 100-person crowd of spectators was heavily Hmong and Pacific Islander. The winner, an airport baggage ramp supervisor named Ben Saunoa, went home with $888.

Pho is a distant, Asian cousin of the French beef stew pot-au-feu (notice how “feu” sounds like “pho”), and it was born during the French occupation of Vietnam. In some parts of the country, it might be eaten for breakfast or as a bedtime snack. Andrea Nyugen, an Asian food expert and author of the cookbook Into the Vietnamese Kitchen, told me what’s in your bowl can offer clues about the geographic origins of the recipe.

If the broth is on the sweet side and has fried garlic or shallots, then the pho has a Lao or Hmong influence. More greens and a very large bowl is more often served in South Vietnam. In the north, the bowls are smaller and the greens less plentiful, she said.

It’s a cold climate in Anchorage, so hot soup has a natural appeal.

Chhuem’s soups are more traditional Vietnamese and are less sweet. An oily oxtail version is very popular at his shop. At Pho Lena East, my go-to place, soup is done Lao-style, with fried garlic, which is more common in Anchorage. One of Pho Lena’s most popular bowls comes with meatballs made with lean beef that is ground in-house. “A lot of Lao people will not eat pho without meatballs,” said owner Biponh Morisath-Luce, whose big Lao family owns three pho shops, one on Boniface Parkway, one downtown, and one in Spenard.

Pho has taken off across the United States, but especially in parts of California, Nyugen said. Part of that is driven by Asian immigration, and part of it is because of the wide appeal of this food. “It’s easy to eat, it’s relatively inexpensive,” she said.

Morisath-Luce and Chhuem told me that a combination of things make Anchorage a good market for pho. It’s a cold climate, so hot soup has a natural appeal. There is also a big military presence here, and military members tend to be well-traveled, adventurous eaters. The city’s diversity helps:

Depending on how you parse the numbers, Asians and Pacific Islanders are now either Anchorage’s largest or second largest minority group, behind Alaska Natives. But to say immigrants drive the market would be an over-simplification.

At Phonatik, the regulars come in waves. Late in the evening, when the nail shops close, Vietnamese manicurists come in, Chheum said. On Sunday, after church, it’s Samoans, Filipinos, and Koreans. When the bars close, it’s a younger, mixed-race crowd. Lunchtime, it’s business people from all kinds of backgrounds. The scene inside the shop is a little picture of Anchorage.

The last step in Chheum’s Pho 101 is constructing the bite. People have differing opinions about how this should go. Chhuem teaches newbies the “pho shot” technique. Fill your wide spoon with meat, greens, and, possibly, chili sauce. (Chili sauce, made of ground peppers and oil, is its own thing. Many shops in town make their own.) Pho is also often served with Sriracha sauce (hot and garlicky), fish sauce (salty), and hoisin sauce (sweet).

Purists say those flavors pollute the broth, kind of like putting ketchup on a gourmet meal, but people can add those sauces to the spoon if they like, Chheum said. Then it goes in your mouth. It should burn just a little. “Chase it with broth,” he said. “Then chase that with noodles, kind of like eating bread.”

This is how to eat pho if you have some time and want to savor it, he said. Taking time makes it easier to power through the whole gigantic bowl. But pho is essentially fast, warm, comfort food. If you’re in a hurry, Chhuem said, just put everything in the bowl (the hot broth cooks the rare beef) and slurp away.

__________________________________

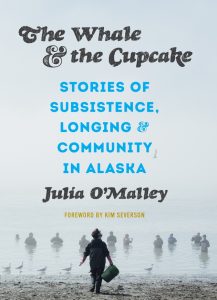

Chapter 5 from The Whale and the Cupcake: Stories of Subsistence, Longing, and Community in Alaska by Julia O’Malley (University of Washington Press, 2019). This excerpt has been printed with permission from the University of Washington Press.

Julia O'Malley

Julia O’Malley is an Anchorage-based food journalist, writing teacher, and editor-at-large at the Anchorage Daily News, for which she writes recipes and a regular Alaska food newsletter. She was the Atwood Chair of Journalism at the University of Alaska Anchorage from 2015 to 2017 and now teaches writing workshops around the state. She has written about food, climate, and culture for the Guardian, Eater, National Geographic, High Country News, and the New York Times, among other publications. She won a 2018 James Beard Award in the foodways category.