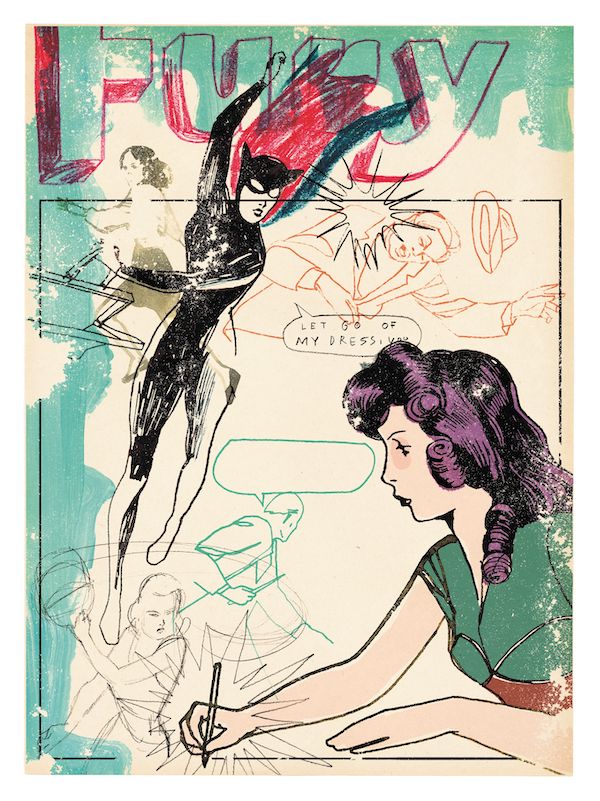

On the Radical, Popular Creator of the First Female Superhero

How June Tarpé Mills Captured Audiences

In 1938, the release of Action Comics #1 changed the world forever when it introduced America to a fella by the name of Superman, and the superhero genre was born. That was the beginning of what is known as the Golden Age of comics.

Three years later, in April 1941, another game changer showed up: the first female superhero. Nope, not Wonder Woman—she would arrive eight months later in her star-spangled blue skirt (the high-waisted control-top briefs would come later). No, the FIRST female superhero was Miss Fury, created, written, and drawn by Tarpé Mills, who also happened to be a woman.

June Tarpé Mills was born in Brooklyn in 1912 or 1918, depending on the source. She was raised by a single mother, a widowed working woman who raised June and the children of June’s deceased sister. Mills worked as a model to help support her family and then to put herself through New York’s prestigious Pratt Institute, where she studied fashion illustration. Side note: Pratt Institute, founded in 1887, was one of the first colleges in the country open to all people, regardless of gender, race, or class.

After a brief stint as a fashion illustrator, Mills started her comics career with her first comic, Daredevil Barry Finn, published in 1938 by Centaur Publications. As cartoonist and historian Trina Robbins writes, “From the beginning, Mills signed her comics with her sexually ambiguous middle name, a French-sounding version of her Irish grandmother’s maiden name, Tarpey.” Mills later told the New York Post, “It would have been a major let-down to the kids if they found out that the author of such virile and awesome characters was a gal.”

Mills’s career was going swimmingly, with her work regularly appearing in Amazing Mystery Funnies, Reg’lar Fellers Heroic Comics, and Target Comics, as she crafted such stand-out characters as the Catman and the Purple Zombie. However, the more coveted job in comics back then was the steady and reliable work of a weekly strip in a newspaper. This prestigious gig was not easy to come by, but in 1941 Tarpé Mills’s tremendous artistic talent and glamorous flair led her to sign a contract with the Bell syndicate to begin writing her game-changing Sunday strip The Black Fury (which soon became Miss Fury), featuring the first major female superhero ever.

It is the men who pine in Miss Fury.

With Fury, Tarpé Mills introduced the world to smart and seductive socialite Marla Drake, whose origin story as Miss Fury slyly thumbs its nose at the traditionally macho conventions of the superhero genre. Marla finds out that she and her friend Carol are wearing identical gowns to a masquerade ball. So, instead, she dons a skintight black leopard suit that had been given to her by her uncle and that once belonged to an African witch doctor. On her way to the soirée, Marla accidentally stumbles into vigilantism when she helps recapture an escaped murderer, disarming him using her suit’s claws, her quick thinking, and a puff of powder blown from her compact. And just like that, Miss Fury was born. Hey, I know it’s not being bitten by a radioactive spider . . . it’s better.

Illustration by Tina Berning

Illustration by Tina Berning

In November 1941, seven months after the strip began, The Black Fury was renamed Miss Fury. Even leading Tarpé Mills expert Trina Robbins doesn’t know why. It’s possible the change was made to really hit home that this superhero was a female, the likes of whom had never been seen before. The strip also reflected what was happening in the American workforce: women taking on roles and jobs previously reserved for the men who were now away, serving overseas. Fittingly, instead of random bad guys and gangsters, the villains in Miss Fury soon became colorful, wild, and weird Nazis, including archnemesis Erica von Kampf (yes, my friends, Kampf), a sexy spy who concealed a swastika-branded forehead beneath her bangs.

Miss Fury’s popularity exploded, and there was no way for Mills to continue being an anonymous creator who hid behind an idiosyncratic, gender-neutral name. When the truth was discovered, newspapers hopped on the red-hot story that Tarpé Mills was in fact a dame! The Fury strip had been running for about a year when the New York Post announced on April 6, 1942: “Meet the Real Miss Fury—It’s All Done with Mirrors.”

Tarpé Mills not only created the first female superhero and not only was she herself a woman, but she based the look and style of her glamorous protagonist on herself. Yes, Marla/Miss Fury LOOKED like Mills. A woman in 1941 creating a female superhero was groundbreaking enough; the fact that said superhero was made in her own image is stunning. It’s no wonder the newspapers all viewed Mills as fabulous World War II-era fodder. Soon Mills was being featured in Time magazine and the Miami Daily Herald. According to the Tarpé Mills website, images of Miss Fury in her black catsuit went on to adorn the nose of “no less than four B17 and B24 bombers, serving in the European and South Pacific theatres.” Tarpé Mills and her creation were a sensation.

While there has been progress, comics have far too often featured female characters who existed for the sole purpose of being saved by the male protagonist, or, an even worse fate, they were “fridged,” a contemporary term that refers to the slaying of a female character to intensify the hero’s motivation and move his story forward, making her a plot device rather than a fully realized character. The term, coined by legendary comic book writer Gail Simone, who also coined “Women in Refrigerators,” was inspired by an issue of Green Lantern, in which Kyle Rayner, the title hero, comes home to find that his girlfriend, Alexandra DeWitt, has been killed and stuffed in the refrigerator.

There would be no “fridging” in Tarpé Mills’s work. She had a very different idea about what female comic characters could and should be: complex, capable women who didn’t need superpowers or a man to get shit done. In Mills’s slyly subversive world, it was the men who often needed saving and who were portrayed as lovesick, with sappy and tortured thought balloons above their heads.

Even in Wonder Woman, which was created by the self-proclaimed feminist William Moulton Marston, the superheroine pines over love interest Steve Trevor. The author even goes so far as to depict Diana Prince as being jealous of her own alter ego because Steve fancies Wonder Woman more. Tarpé Mills was downright radical in her portrayal of Marla Drake as someone who had more than one love interest and who never pined over men. It is the men who pine in Miss Fury.

It’s such a shame that while Wonder Woman flourished, Miss Fury faded from memory and has little to no legacy.

Another striking thing about Miss Fury is that Marla Drake is sharp and skillful even when she is not in the black catsuit. The comic consistently highlights Marla’s depth of ability, like showing her on a fishing trip, angling effortlessly before she runs off to battle evil. Even her physical conquests are portrayed as being possible because of her wits. Unlike Diana Prince, Marla Drake does not have superpowers, yet she is more self-reliant and independent than her Amazonian peer. Nor is she a super genius who achieves feats outside the realm of possibility to readers. She is a viable and relatable hero who is simply courageous and competent and who happens to be a grade-A hottie.

One of Tarpé Mills’s unparalleled contributions to comics was how she added a level of hyper detail and accuracy to her characters’ wardrobe, her background in fashion illustration serving her well. It was the first time in comics that such attention was given to fashion. Previously, characters, mostly drawn by men, appeared in simple blue suits or basic red dresses, but as the Los Angeles Review of Books puts it, “Miss Fury, by contrast, is midcentury clothes porn.”

The comic won over both men and women. There was action and intrigue and sexiness and feminism and depth of character and fashion and WOW. Come for the ten-panel catfight between Miss Fury and hot Nazi Erica von Kampf, wrestling on a rooftop in gauzy lingerie, stay for the fashion, female empowerment, and making men the lovelorn puppies. Something for everyone!

Halfway through the series, Marla, dissatisfied with only fighting bad guys, gets a job, and—shockingly, for the times—adopts the abandoned baby of her chief adversary, Erica, becoming a single mother. Tarpé Mills not only gave her readers a female character who defied all societal expectations and gender norms, she also gave the world the first depiction of a superhero who was a mom when positively portraying a single mother, one who had agency, was simply unheard of.

After the war, American women lost their jobs to returning servicemen (because duh, you’ve had your fun being strong and capable but get out of the way, the men are back), and the energy began to shift around how women should be portrayed in comics. One wouldn’t think comics would be so policed, but in conservative postwar America, the daddies—I mean men— in charge thought that comics were corrupting young minds and even began linking juvenile delinquency to the increasing number of unconventional comic-book heroines. By 1954, the Comics Code Authority was formed. To meet code approval, a comic couldn’t be lurid or excessively violent, and women were to be portrayed in traditional gender roles. It was in this climate that Miss Fury’s run came to an end. Couldn’t even let us have make-believe.

It’s such a shame that while Wonder Woman flourished, Miss Fury faded from memory and has little to no legacy. It ran for more than a decade, from 1941 to 1952, and was syndicated in one hundred different newspapers at the height of its wartime fame. Timely Comics (now Marvel) obtained the rights to reprint the strips in comic-book form and ran it as a series from 1942 to 1946, selling a million copies an issue.

Even though Miss Fury and Tarpé Mills are both feminist icons, there is no biography about Mills’s life, which is utterly disappointing and why much of this chapter is about Miss Fury, not Ms. Mills. One can barely find the compilation volumes of Miss Fury (published by IDW in 2011 and 2013), as they are out of print. If Timely reprinted the strips in the 1940s and Timely has since become Marvel, why isn’t Marvel all over the Miss Fury legacy and resurgence? WHERE’S THE MISS FURY MOVIE?

In 2019, Mills’s work and legacy were finally recognized with her induction into the Eisner Awards Hall of Fame at Comic-Con in San Diego. There she resides—finally—where she belongs, alongside the other, mostly male, creators of the Golden Age. In the beginning, Mills may have felt compelled to hide her gender, but she never hid her convictions about female empowerment and self-sufficiency in her work. She also had a style no one could touch. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I need to go daydream about which actress should star in the film.

__________________________________

From Let Me Be Frank: A Book About Women Who Dressed Like Men to Do Shit They Weren’t Supposed to Do by Tracy Dawson. Copyright © 2022 by Tracy Dawson. Reprinted courtesy of Harper Design, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Top image credit: Illustration by Tina Berning

Tracy Dawson

Tracy Dawson is a Canadian American actor and writer who began her career at the world-renowned Second City in Toronto. The winner of numerous acting and writing awards, she wrote for and performed as a lead actor on the television series Call Me Fitz starring Jason Priestley, for which she won the Gemini Award and the Canadian Screen Award for Best Lead Actress in a Comedy Series. Her play, theM & us, was produced by Theatre Passe Muraille in Toronto. Tracy has acted in countless projects on stage and screen, including Disney Channel's Girl vs. Monster, and has sold several television projects in the United States and Canada. Born in Ottawa, she lives in Los Angeles with her life partner, Isaac, who is a Dog. Let Me Be Frank is her first book.