On the Precocious Early Years of Marie Antoinette

Nancy Goldstone Recounts the Freedom of Life Before Marriage to Louis XVI

Marie Antoinette was born on November 2, 1755. Just a year earlier, an overeager American colonial had exceeded his orders and opened fire on a sleeping French reconnaissance unit, rekindling hostilities between England and France. The crisis had driven Maria Theresa into a treaty with Louis XV, arranged surreptitiously through Madame de Pompadour. Thus, it could be argued that, since both her youngest daughter and the Austrian-French alliance came into being at more or less the same moment in history, it was George Washington who put Marie Antoinette on the throne of France.

Toinette, as she was nicknamed (although she was also often referred to simply as “the little one”), was her mother’s 15th child and youngest daughter. She was exceptionally pretty, all big blue eyes, blond curls, and merry disposition, not unlike Maria Theresa herself as a young girl. Marie Antoinette was her father’s favorite: Francis loved the sweet smiles and adorable prattle of this last baby girl, and indulged her affectionately. Of all his children, she most resembled him, not so much in looks as in nature—she was highly social and at her best in company (and, like him, somewhat less successful in the schoolroom).

There is a charming account of a gathering at Schönbrunn on October 13, 1762, just three weeks before Marie Antoinette’s seventh birthday, when a pint-sized musical prodigy by the name of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was invited to entertain the imperial family. As the visiting musician was himself just six years old, all of Maria Theresa’s children, even those in the younger group, were allowed to attend the performance. Mozart immediately won the heart of the empress by leaping onto her lap and giving her a kiss. Francis was similarly captivated, calling the boy “the little sorcerer” when he responded to a teasing dare of the emperor’s by effortlessly playing the harpsichord with all the keys covered.

But it was Marie Antoinette who made the most vivid impression on the small savant who would grow up to become one of the most brilliant composers in history. Unused to the polished floors of the palace, at one point during his audience (which lasted three hours), Mozart slipped and fell. Before he could right himself, winsome little Marie Antoinette ran to him and picked him up. “You are good,” he exclaimed with a mixture of gratitude and obvious admiration. “I shall marry you!”

Marie Antoinette was her father’s favorite: Francis loved the sweet smiles and adorable prattle of this last baby girl, and indulged her affectionately.

She was too young to know it, but this lighthearted encounter was one of her mother’s few intervals of levity that fateful year. At the same time that the diminutive Mozart was enthralling Marie Antoinette and her family with his musical parlor tricks, Frederick the Great, having been saved from a crushing defeat by the fortuitous death of Empress Elizabeth, was busy retaking Silesia and Dresden, and a shattered Maria Theresa understood that the war into which she had poured all her hopes, and the horrors of which she had inflicted on her loyal subjects for the past six years, was irretrievably lost.

Small wonder, then, that the emperor and empress sought to divert themselves with children whose innocent antics made for such a refreshing contrast to the cares of adult life. It was soon after the Mozart recital that Maria Christina painted the portrait of her parents at the holiday breakfast table, and there is seven-year-old Marie Antoinette, proudly holding up her new doll, significantly the only younger daughter present, secure in her position as treasured pet of the family.

This she remained through the heartache of the next few years, which included the loss of first her sister Maria Johanna, nearly 12 to Marie Antoinette’s 7, and then her brother Joseph’s first wife, Isabella, both to smallpox, when she was 8. In those dark days, Marie Antoinette’s ready laugh, bright little face, and affectionate demeanor gladdened her parents’ hearts. She was a darling, uncomplicated child, existing entirely on the surface, and these qualities were rewarded with adult approval.

Her mother, it is true, intimidated her—Maria Theresa was the disciplinarian in the family—but her easygoing father softened the rigor imposed by the empress, and Marie Antoinette worshipped him. On the hot July morning in 1765 that her parents and older siblings left Vienna to travel to Innsbruck in preparation for her brother Leopold’s wedding—the younger children, as usual, being left behind—with everyone already ensconced in their carriages ready to go, Francis, much to Maria Theresa’s irritation, insisted on holding up the entire procession until nine-year-old Marie Antoinette could be brought out to him for a last tender embrace. “I longed to kiss that child,” Francis explained, by way of excuse for the delay. His daughter never saw him again. Her mother returned from that fateful journey a broken, black-clad widow, but the little one would remember this final testament of her father’s love for the rest of her life.

For the next two years, like her next-eldest sister, Maria Carolina, with whom she spent most of her time, Marie Antoinette floated just outside the periphery of her mother’s attention and so was allowed the freedom of a relatively carefree childhood. These were the days of the lax first governess, whose directives were so effortlessly evaded; of hours spent giggling and pretending with Charlotte; of picnics and playing in the garden.

Unlike her clever sister, however, who liked to read and found her lessons tedious because they were too simplistic, Marie Antoinette had neither the discipline nor the aptitude for scholarship. Her attention span was extremely limited; she disliked reading; she had not the focus even to learn to form her letters properly. As her mother demanded to see all of her written schoolwork, this presented a problem until her governess settled upon the happy expedient of first composing Marie Antoinette’s papers for her in pencil, after which her disinterested pupil would dutifully trace over the markings in ink.

Marie Antoinette had neither the discipline nor the aptitude for scholarship. Her attention span was extremely limited.

Then came the fateful autumn of 1767, and with it the death of Maria Josepha and the hurried substitution of Maria Carolina as the sacrificial bride of the puerile king of Naples. By the summer of 1768, Marianne having already gone into the Church, there were only three unmarried archduchesses left in Vienna: 25-year-old Maria Elisabeth (whose Sardinian suitor had backed out due to the rumors of the ravishment of her face), 22-year- old Maria Amalia (still in love with the penniless prince of Zweibrücken), and 12-year-old Marie Antoinette. And for these three potential brides there were two realms that Maria Theresa was absolutely determined to marry into: Parma, to return the duchy to Austrian interest and thereby recover her inheritance in Italy; and France, to secure the alliance that was the great work of her reign and ensure a lasting peace with what had for centuries been the empire’s foremost antagonist.

But as much as she—urged on by Joseph and especially her principal minister, Count Kaunitz (upon whom she relied even more heavily, if that was possible, after Francis’s death)—pressed the French for a firm marriage commitment between the dauphin and Marie Antoinette, Louis XV, while not opposing the idea in principle, nonetheless did nothing to promote it, either. Since the death of Madame de Pompadour in 1764, the king of France had become even more indolent, preferring to occupy himself with his new mistress, Madame du Barry, a former streetwalker-turned-courtesan, rather than apply himself to the business of government or foreign policy.

Then, on June 24, 1768, the queen of France, Louis’s long-suffering wife of 43 years, died. She left behind four adult daughters, all of whom deeply resented Madame du Barry. These princesses, having never been espoused, resided at Versailles. Determined to prevent the humiliation of having their father’s vulgar, déclassé mistress replace their mother at court, they came up with the happy solution that 58-year-old Louis XV honor his marital commitment to Austria not by wedding his 13-year-old grandson, the dauphin, to Marie Antoinette but rather by taking one of her older sisters as a new wife for himself. When Louis pronounced himself amenable to this option (his one stipulation being that the bride in question be young and beautiful), they suggested Maria Elisabeth, whom they clearly knew only by her pre-smallpox reputation.

If this dubious last-minute gambit had succeeded, there is a slim chance (although still very unlikely) that Marie Antoinette might have sidestepped destiny and gone to Parma, where she was exactly the right age and temperament for the duke, and where she could have lived as she liked and been happy, and that Maria Amalia would then have been able to marry for love, as had her sister Maria Christina. But Louis was suspicious and sent a portrait painter to Vienna; the artist confirmed the rumors of Maria Elisabeth’s ruined complexion. In a clear win for Madame du Barry, he gave up on the idea of remarriage altogether and instead officially agreed to a wedding between Marie Antoinette and the dauphin.

On June 4, 1769, the king of France affirmed the glad tidings to Maria Theresa by means of a personal letter: “Madame my Sister and Cousin,” Louis wrote. “I can not delay much longer . . . the satisfaction which I feel about the forthcoming union which we are going to form by the marriage of the Archduchess to the Dauphin, my grandson . . . This new tie will more and more unite our two houses. If your Majesty approves, I think that the marriage [by proxy] should take place in Vienna soon after next Easter . . . I shall do here what I can, and so will the Dauphin, to make the Archduchess Antoinette happy,” he assured her graciously.

And it was at this point that the fates of Maria Theresa’s two older unattached daughters were sealed. Having run out of nominees—somebody had to marry the duke of Parma—Maria Amalia, much against her will, was volunteered for the position. To ensure that there was no backsliding, Joseph himself escorted his sister south to Italy, where, on July 19, 1769, she married Isabella of Parma’s 18-year-old brother, whose maturity was on par with that of his cousin the king of Naples, and who subsequently proceeded to be overshadowed in every way by his unhappy, resentful bride. Maria Elisabeth, sentenced by the rejection of the French king to spinsterhood and ultimately, like Marianne, the Church, was even more distraught than Maria Amalia when the news was broken to her. “She began to sob . . . [saying] that all [the others] were established and she alone was left behind and destined to remain alone with the Emperor [Joseph], which is what she will never do,” Maria Theresa confided in consternation to a friend. “We had great difficulty in silencing her.”

But maternal distress over her older daughters’ wretchedness was offset by Maria Theresa’s satisfaction with her youngest’s good fortune. The kingdom of France, home to some 20 million subjects, was considered the apex of 18th-century civilization. True, England’s navy was the envy of the world, and London might excel at finance and trade, but Paris was universally acknowledged to be the cultural and intellectual center of Europe, and Versailles was still the model for sovereign splendor.

Any woman who ascended the throne of France would be responsible for maintaining the exalted prestige of a monarchy that traced its venerable roots to Charlemagne; she would be an object of envy whose deportment would be emulated both at home and abroad. It therefore came as something of a shock to Maria Theresa when, having removed Marie Antoinette from the care of her old governess and assigned her instead, after the departure of Charlotte, to the more accomplished Countess von Lerchenfeld, it was speedily revealed that not only was the 13-year-old future dauphine incapable of communicating gracefully in French, but she struggled even to read and write.

There seemed no choice but to cram as much education into her as possible in the short time remaining before her departure for France. Toward this end, Maria Theresa had her daughter sequestered at Schönbrunn Palace along with a gaggle of instructors, including Viennese experts in music and art, as well as a specially imported Parisian ballet master, for Marie Antoinette required coaching in elegant posture, the mechanics of making an entrance and gliding gracefully across a room, and state-of-the-art curtsying. However, even this wasn’t considered good enough for the future wife of the dauphin, so Versailles also sent its own tutor, the abbé Vermond, to ensure that the archduchess was properly educated in French history, language, and literature.

Any middle school teacher will sympathize with the abbé’s predicament. He wasn’t there two days before he realized that his pupil, while undeniably charming and well-intentioned, was so far behind, and had so many other demands upon her time, that it was going to be impossible to get her to read anything on her own; whatever information she absorbed was going to have to be spoon-fed to her. “After devoting my first instructions to the object of acquainting myself with the turn of mind and the degree of H.R.H.’s [Marie Antoinette’s] knowledge, I arranged . . . the method of learning I considered most useful to Madame the Archduchess,” he reported home in his initial communication of June 21, 1769, from Vienna. “In order to diminish the wearisome nature of the studies, I keep them as much as possible to the forms of conversation,” he continued tactfully. “I cannot speak highly enough of the docility and goodwill of H.R.H., but her liveliness and the frequent distractions militate insensibly against her desire to learn.”

Six weeks later he was still gamely pursuing the same strategy, albeit with slightly more desperation. “The Archduchess will say the most obliging things to everyone,” he reassured his superiors. “She is cleverer than she was long thought to be. Unfortunately, that ability was subjected to no direction up to the age of 12. A little idleness and much frivolity rendered my task more difficult . . . I could not accustom her to get at the root of a subject, although I felt she was very capable of doing so. I fancied I could only get her to fix her attention by amusing her,” he admitted. By October 14, 1769, two weeks before Marie Antoinette’s 14th birthday, he was able to report with evident relief that at least her pronunciation had improved, so that she now “talks French with ease, and fairly well.”

His optimism in other areas, however, clearly had been worn down in the face of his student’s fundamental inability to focus. “She would rarely make mistakes in spelling if she could only give her undivided attention,” he burst out in a rare moment of candor. “What is most vexing is that partly through idleness and inattention . . . she has acquired the habit of writing inconceivably slowly . . . I often occupy myself with this . . . but I own that on this point I have made the least progress,” he lamented.

But of course the true victim in all this was the prospective bride herself. As yet, Marie Antoinette demonstrated no inclination to rebel against parental authority; her demeanor and temperament remained sweetly obedient; her sole desire was to please the adults surrounding her. It was just that (with the invention of Ritalin still being some 200 years in the future) the effort required was outside her capabilities. Granted, it was unlikely that even under the best of circumstances Marie Antoinette would have developed a taste for serious reading or critical contemplation, but if she had been allowed to continue to receive instruction at home until her later teens she might at least have learned not to shun these occupations so thoroughly. As it was, the principal lesson she came away with from this intensive, months-long course in academics was to regard any time spent on books and intellectual pursuits as a punishment.

While the bride was thus occupied with her studies, preparations for the marriage ceremony and the journey for France progressed diligently. On January 21, 1770, the bejeweled ring sent by the dauphin to formalize the engagement was ceremonially slipped onto Marie Antionette’s finger; this milestone was followed three months later, on April 16, by the arrival of the embassy charged with representing the groom’s interests at the upcoming festivities. The French ambassador’s impressive retinue and equipage included a magnificent, elaborately ornamented carriage, boasting much glass on the outside and satin on the inside, that had been expressly constructed to convey the dauphine to her new home.

Three days of solemn rites and extravagant celebrations followed. There was an evening of theater, with a new ballet written and choreographed by the renowned French master in honor of his student. The next day, Joseph hosted a formal state dinner for 1,500, complete with gold and silver plate, with a gorgeous masked ball and fireworks afterward. Not to be outdone, the French ambassador presided over a similarly brilliant gathering, dazzlingly illuminated by an even showier display of bursting colored rockets and night sparklers.

The proxy ceremony itself took place on the evening of April 19, 1770, at the Church of the Augustinian Friars. Marie Antoinette, radiant in a cloth-of-silver gown with a flowing train, was led down the aisle by her mother; her brother Ferdinand, at a year older almost exactly the same age as the dauphin, stood in for the bridegroom. Maria Theresa and Joseph, seated side by side on thrones, presided over the ceremony in their capacity as co-regents. The bride and her brother the surrogate knelt before them; a papal nuncio led the service; the Te Deum was sung. And, just like that, the youngest archduchess was married.

_______________________________________

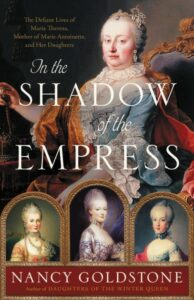

Excerpted from In the Shadow of the Empress by Nancy Goldstone. Copyright © 2021 by Nancy Goldstone. Reprinted with permission of Little, Brown and Company. All rights reserved.

Nancy Goldstone

Nancy Goldstone's books include The Rival Queens, The Maid and the Queen, Four Queens, and The Lady Queen. She has also coauthored five books with her husband, Lawrence Goldstone. She lives in Sagaponack, New York.