On the Power of Essayistic Compression in Flash Nonfiction

Dinty W. Moore Traces the Growth (Contraction?) of a Genre

While it might seem obvious to suggest that a work of many pages, or multiple chapters, could hold more truth than a piece of prose short enough to fit on one page, the opposite view has always had its ardent defenders. Hippocrates adored aphorisms, Pascal penned Pensées, Ben Franklin filled his Poor Richard’s Almanack with pithy proverbs, and Dorothy Parker made her mark partly by dashing off quick and quick-witted barbs.

The literary essay has traditionally favored length over compression as well. After all, if the essay is “A loose sally of the mind […] not a regular and orderly performance,” as Samuel Johnson once suggested, all of that sallying and disorder requires a bit of space. Think David Foster Wallace, Rebecca Solnit, Annie Dillard, Mary Cappello, Virginia Woolf (most of the time), and Montaigne (some of the time).

Yet even where the essay is concerned, there have always been proponents of the brief. The idea of saying plenty in few words resonates in the work of authors such as Seneca, best known for his Moral Epistles, Sei Shōnagon and her diaristic Pillow Book, Charles Lamb, and yes, on occasion, the aforementioned Montaigne. He was a fickle sort.

Likely, this push and pull between long and short, loquacious and pithy, will continue, but for the moment, thanks partly to the limits of social media and a penchant for shorter work in online literary magazines, brief nonfiction is perhaps at peak popularity.

More than 50 literary magazines now specifically solicit flash nonfiction, writers centers such as Grub Street, The Loft, Hugo House, and San Diego Writers Ink offer regular classes in the genre, and college courses centered around very short essays and how they function are taught to graduate and undergraduate students in Arkansas, Iowa, Indiana, Ohio, Utah, and Honk Kong. Rather than being a flash in the pan, flash nonfiction prose has panned out.

Even where the essay is concerned, there have always been proponents of the brief.

My online flash essay magazine, Brevity, was the first to focus on exceedingly concise nonfiction (750 words or fewer), and since it has been publishing for 22 years now, it is not uncommon for folks to hail me as founder of the genre. The truth, of course, is far more layered.

The spark that prompted me to launch Brevity was struck in the mid-1980s, with the arrival of popular short story anthologies such as Sudden Fiction. Around the same time, Florida State University launched the World’s Best Short Short Story Contest, offering a crate of Florida oranges to the person who could come up with the best short short (no more than 250 words). Soon enough, anthologies such as Sudden Fiction International, Micro Fiction, and, eventually, Flash Fiction, established very brief short stories as a genre all their own.

But it was Judith Kitchen and Mary Paumier Jones, no doubt aware of the fiction anthology boom, who started the nonfiction ball rolling. Their anthology, In Short, published by W. W. Norton in 1996, was an immediate influence on nonfiction writers, and is still widely taught. In Short included work by Stuart Dybek, Terry Tempest Williams, Tobias Wolff, Richard Rodriguez, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Naomi Shihab Nye, Donald Hall, Michael Ondaatje, Maxine Kumin, and Barry Lopez, among 83 others, a veritable who’s who of prose writers (with a fair number of poets tossed in the mix).

In his introduction to the volume, Bernard Cooper, whose innovative book of very brief essays, Maps to Anywhere, was released by University of Georgia Press in 1990, quotes Raymond Carver: “Get in, get out. Don’t linger.”

Carver’s admonition is admirably concise, though I favor the longer definition of flash prose that Cooper himself offers a few paragraphs later: “To write short nonfiction requires an alertness to detail, a quickening of the senses, a focusing of the literary lens, so to speak, until one has magnified some small aspect of what it means to be human.”

Kitchen, who edited or co-edited three additional anthologies of brief essays after In Short, championed the genre until her death in 2014. Mary Paumier Jones, Kitchen’s co-editor for the first two volumes, remembers “contacting everyone we knew that wrote in this form for the first anthology. Of course, it wasn’t truly considered a form back then, but so many folks were writing it. What we found, mostly, were little odd bits of things stuck in different places.”

Kitchen and Paumier Jones chose pieces that were intentionally brief, but also excerpts from longer works. Some of the excerpts are easy to spot, in my opinion. True flash, I believe, is written with brevity as a primary intent.

The In Short editors couldn’t quite decide on a name for what they had collected, either. In their introduction, they wrote that “this new short form has no name” but suggested calling them “simply ‘Shorts’.” Dybek remembers when flash fiction was called “shortys,” and occasionally “jockeys,” short for Jockey shorts. Author and editor David Galef recalls the term “blasters.” None of those names caught on, thank goodness.

More recently, Beth Ann Fennelly has offered up the suggestion “micro-memoirs,” which is certainly more dignified, but not all flash nonfiction is memoir.

When I began Brevity in 1997, I too wasn’t quite sure what term to use, contributing to the confusion by advertising our brief work as “micro-essay,” then “brief literary nonfiction,” and eventually “concise literary nonfiction.”

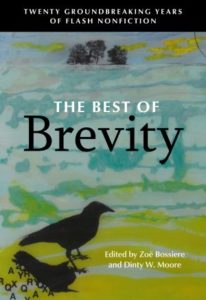

In editing the anthology Best of Brevity, celebrating the 20th anniversary of the online journal, my co-editor Zoë Bossiere and I went with the term “flash nonfiction.” Twenty-four years after Kitchen and Paumier Jones’ first anthology, it is the term now most widely in use, and the most inclusive.

Like poetry, flash often relies on the tiny detail, the single image, or some peculiarity of word choice or phrasing.

But all of this still begs the question of what make the flash genre unique, how it manages to convey so much truth—when done well—in so few words. I’m a firm believer that attempting to nail an art form down too firmly is a fool’s errand, but, Bernard Cooper’s suggestion that flash focuses in on specific details to magnify “some small aspect of what it means to be human” applies well to many of the successful flash essays I have seen over the years.

Like poetry, flash often relies on the tiny detail, the single image, or some peculiarity of word choice or phrasing—small elements that carry a greater load than they might in a longer work.

Another excellent take on flash comes from Atlantic editor C. Michael Curtis, who is speaking of fiction here, but all that he says applies to nonfiction quite well: “The shorter the story, the more both writer and reader have to depend on hard moments of discovery, flashes of illumination that provide, in their suggestiveness and aptness, what other writers struggle for pages to make clear.”

As a reader, I recognize that flash of illumination that Curtis speaks of, in so many of the pieces included in the Best of Brevity anthology. As an editor, that flash point is often what sells me on a piece for the magazine, though I should add this: talking with countless successful flash writers over the years, I’ve learned that they too will often “struggle for pages” to find the heart of the story, but then the paring back begins. Flash is as much erasure as it is composition.

Perhaps Hippocrates most well-known aphorism had it exactly backwards. Not “Ars longa, vita brevis”—“Life is short, and art long”—but “Vita longa, ars brevis!”

Let’s hope our lives are long, even in this virus-plagued, politically troubling world. And yes, art can be brief. Sometimes it works better that way.

__________________________________

The Best of Brevity: Twenty Groundbreaking Years of Flash Nonfiction, edited by Dinty W. Moore and Zoë Bossiere, is available now.

Dinty W. Moore

Co-editor with Zoë Bossiere of The Best of Brevity: Twenty Groundbreaking Years of Flash Nonfiction (Rose Metal Press, 2020), Dinty W. Moore is also the author of the memoir Between Panic & Desire, winner of the Grub Street Nonfiction Book Prize, and editor of The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Writing Flash Nonfiction: Advice and Essential Exercises from Respected Writers, Editors, and Teachers. Find him online at dintywmoore.com