On the Politics of Caste and Feminine Joy in Satyajit Ray’s Classic Charulata

TANAÏS on How the Narratives of Muslim Women and Femmes Are Not Merely About Representation

In a St. Louis library in 1990, I watched our people—speaking our language, eating with their hands—on an American big screen for the first time, in Satyajit Ray’s iconic black-and-white film, Pather Panchali. This is the first film in his Apu Trilogy, a bildungsroman of the lives and tragedies of a young man named Apu. There was never any question of whether we, as Bangladeshi Muslims, saw ourselves in these Hindu characters living in rural West Bengal—they were our people too.

Whereas books, the form I felt most drawn to, let my imagination run wild, I revered the emotional textures of this film. You cannot look away, neither from the suffering nor the joy. I wept when his sister, Durga, died from a fever, after dancing in the monsoon rains. I wept in the next two films, when Apu loses his mother, and his wife. The beauty of the trilogy imprinted itself on me as an artist, but so did the realization that feminine joy is short-lived in Satyajit Ray’s films.

In 2021, I revisited Ray’s prolific oeuvre. First up: Charulata, a story about a young bhadramahila, an upper-caste gentlewoman, set in late 19th-century Bengal. It felt so relevant to me as I wrote a book, locked inside my home during quarantine, which made the character Charulata’s plight intensely relevant. Stuck in the inner quarters of a palatial home, the zenana, Charulata passes time by playing card games with her sister-in-law, whom she can’t stand, embroidering slippers, devouring books, and fixing tea for her husband, a man much older than she is.

I kept wondering: Where are my people in this film about wealthy Bengal Brahmins from West Bengal living on giant estates?

Too preoccupied with his newspaper and the rising freedom struggle against the British to pay her close enough attention, her husband arranges for his cousin, Amal the Poet, to come stay with them to keep her company. He’s much closer to Charulata’s age. This is where the delicious trouble begins. Besides living for free in a mansion, the Poet’s task is to encourage her writing— even though Charulata is already a far better writer than he is—and each day that passes, her repressed sexuality is awakened.

(O, the eons of pedophiles arranged-married to child wives lost to younger men!)

*

In one of the most hypnotic moments in the film, Charulata rocks on a tree swing, breathes heavy, stares at the sky, mad—as in angry—with desire. From the angle of the camera, Ray makes sure we are close to her face, her breath, the rocking; we feel how much she wants to be fucked by this young man—how much she hates herself for this unshakable longing. With no way to expel their lust, the sweet, simple foreplay between herself and the Poet is a song, one that I recognized immediately. “Phule Phule Dhole Dhole”—“Flowers sway in the breeze.”

This was the first Bengali song I learned from my father. I remember Baj in his swimming shorts, transitioning my sister and me from baths to showers. I had no idea then that this song belonged to this film; when I sang it, I felt as though I was in my own world, unaware and unafraid of midwestern neighbors who hated our religion, our brown skin pearled and wrinkled by the falling water, our music, crystalline, bouncing off the walls.

*

Charulata writes a brilliant piece about her village for a paper that the Poet is too afraid to pitch to himself, and he realizes that she’s way out of his league. When she falls into his arms, crying, “I’ll never write anything again!,” he also realizes that she’s in love with him. Her tears flow, from the confusion, the guilt of writing him into oblivion, from knowing she’ll never have him. Maybe the Poet is in love with her too. But he can never love her back—he would lose everything. And so, he leaves her, in the middle of the night.

(O, the husband is hotter than Amal, a fuccboi, but who can resist a Poet?)

*

Charulata is based on a novella, The Broken Nest, written in 1901, by the first Indian Bengali Nobel Laureate in Literature, Rabindranath Tagore, who also penned the lyrics to her song. Some say that the Poet’s closeness to Charulata mirrored Tagore’s real-life relationship to his sister-in-law Kadambari Devi. She was his elder brother’s ten-year-old child-wife. In her husband’s long absences from home, her bond with young Rabi, her peer, grew stronger. Did the two of them steal time away from the house? Or perhaps, on a rare afternoon, when they had the house to themselves, did they ever experience their forbidden love? When it came time for Rabindranath to marry, he, too, chose to wed a 10 year old child, Mrinalini, whose father worked on his family’s estate.

What does it mean to be diaspora, stripped of the unreasonable project of universality, and instead be intensely committed to decolonization and decentering hegemony, all the while crackling with sensuality and rage?

Four months later, Kadambari Devi overdosed on opium. Was death easier to face than losing the love of her life whom she’d never have?

*

A moment comes and goes in the film, nearly imperceptible:

One afternoon, Charulata dishes with the Poet about all the beautiful women in her favorite author’s books. She curls her lip when she names one of them, Lutfunessa—Arabic for “grace of women”—and describes her as plain, dark-skinned, thin-lipped, not-as-pretty-as-the-others. (Her problematic fave author is Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, the novelist and the composer of “Vande Mataram,” impassioned song of the Swadeshi movement to free India. To this day, the tune lives on as a Hindu nationalist anthem that represents the right-wing, fascist factions of India.)

Bankim represented the essence of the Bengali bhadralok, the people of Charulata and the Poet’s economic class. He dreamt of a Hindu rashtra, India as a Hindu homeland, free from British rule. His writing—lauded for its lyricism—crackled with disdain for Muslims. His words were powerful enough to influence the first Partition of Bengal, a foreshadowing of the ultimate, and terribly violent, Partition of India in 1947, which would split South Asia into India and Pakistan. It makes sense that a woman of Charulata’s class and caste would read Bankim’s work. Despite the ways I related to her character, a young writer caught like a caged bird between wifehood and sexual longing who escapes into books, I kept wondering: Where are my people in this film about wealthy Bengal Brahmins from West Bengal living on giant estates?

Lutfunessa, the dark-skinned, unpretty character in Bankim’s work, is the sole Muslim woman, a ghost in this work of art. This Muslim woman could be from East Bengal, which would become East Pakistan and, ultimately, Bangladesh. This woman had the same name as my dadi, my paternal grandmother. Lutfunessa. Our ancestral narratives remain partitioned in a spectral zenana, lost in the inner, inner chambers of the upper-caste bhadralok consciousness. From their perspective, you’d never know that Muslim women were writers or dreamers, because their loves, heartbreaks, and sexual desires never made the final cut.

*

And so, I wonder, what became of Charulata?

After her husband witnesses her crying wildly for the Poet, he rides around aimlessly in a carriage, distraught. He returns home, and Charulata reaches her hand out to him. “Esho,” she says. (“Come.”) Satyajit Ray’s use of still photographs represents the last moments we see Charulata and her husband. Reaching for each other. Holding hands. Staring off into the middle distance—an impasse. The possibility of a future. Did Charulata’s marriage ever become bearable, or even joyous? Did she and her husband ever start their magazine together? Did they have a child? Did she become a young widow? Did she commit suicide?

*

After the screening of Ray’s film, another decade passed before I read Bangladeshi characters in English (albeit British ones) in Zadie Smith’s White Teeth. Fiction by non-Black and non-Indigenous people of color is oft centered on the immigrant narrative, and within the South Asian diaspora, the dominant culture of Indian, upper-caste, and Hindu is the story centered over and over again. And in modern film and television, where there is undeniably more representation of South Asians than when I was growing up, still these stories are centered on the experiences of Indians and Indian Americans. South Asians from Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, or Bhutan are rarely a part of the narrative; we are invisible Indians.

What does it mean to write at the edges? What does it mean to be diaspora, stripped of the unreasonable project of universality, and instead be intensely committed to decolonization and decentering hegemony, all the while crackling with sensuality and rage?

*

I am the child of Bangladeshi immigrants who arrived less than a decade after the Liberation War in 1971, a final Partition of East and West Pakistan. I am their firstborn daughter, raised in the South and the Midwest before we finally settled in New York. But I’m writing an experience that is not theirs, an experience that is still emerging into the American consciousness.

In the States, Muslim voices, art, and lives celebrated by dominant cultural imagination are oft required to mute or diminish their overt Muslimness. We are asked to deny our historic and lived relationship to imperialism, violence, and erasure, especially post 9/11. I know the shame of hiding the truest parts of me—during the Gulf War, my parents warned me never to tell strangers our last name, Islam—these parts that complicate an Asian American or South Asian American identity: I am Muslim. I am Bangladeshi. I am American.

As I am a non-Indian Bangladeshi Muslim, the pain of my brownness is not just that I am invisible to white or Black people; it is that my people—Muslims—are considered to be difficult, dangerous, dissenting, the world over. Not only by white people, but by our own South Asian kin. Writing the narratives of Muslim women and femmes is not merely about representation. Writing defies the silencing of our truths, eschews any flattening. We are not oppressed, silent and broken by violence. Writing ourselves in our fullness and complexity gives us a future. Our foremothers—Lutfunessa—were never imagined as a part of history, even though their stories are older than any nation.

___________________________________________

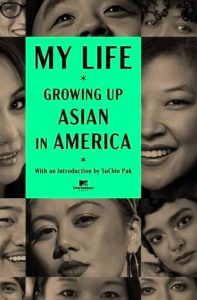

From My Life: Growing Up Asian in America by CAPE, the Coalition of Asian Pacifics in Entertainment. Compilation and Introduction copyright © 2022 by Simon & Schuster, Inc. “Bangla, in Black and White” copyright © 2022 by Tanwi Nandini Islam. Reprinted by permission of Atria Books/MTV Books, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc

TANAÏS

Tanaïs is the author of In Sensorium and the critically acclaimed novel Bright Lines, which was a finalist for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize, the Edmund White Debut Fiction Award, and the Brooklyn Eagles Literary Prize. They are the recipient of residencies at MacDowell, Tin House, and Djerassi. An independent perfumer, their fragrance, beauty, and design studio, TANAÏS, is based in New York City. Follow them on Instagram at @studiotanais.