On the Particular Thrill of Visiting a Dead Writer's House

Phoebe Hamilton-Jones in Praise of Literary Tourism (Done Well)

It is always curious to see how other people live, their very particular paraphernalia. Who hasn’t, upstairs in someone else’s house, looking for the bathroom, nudged open a second door?

So imagine being able to do this at your favorite author’s house: seeing the writing desk, the agates laid on the window sill, the threadbare spines of the books they thumbed.

It’s not easy to pull off literary tourism, and literary museums in particular. Perhaps unsurprisingly, books don’t translate well into gallery spaces. I’ve been to a few literary museums and they have ranged from the absurd to the dull—artifacts in aspic, illegible letters behind glass, a wall of Ulysses copies in myriad translations. In a pub off the motorway in Cornwall, waxwork figures with crude voiceovers narrate Daphne Du Maurier’s Jamaica Inn. In Dublin’s James Joyce Centre, the visitor encounters a strange mix of corny murals, Joyce’s death mask, and a TV in the main room playing the 80s adaptation of “The Dead” on loop.

But dead writers’ houses have an unsettling thrill which makes them the kind of literary tourism I’ll sign up for. From Hemingway’s house in Cuba, where dozens of cats are buried in the garden; to Keats’ austere home in Hampstead; to the Red House where the Pre-Raphaelites hung out and bickered. These intimate time warps call on our imagination; they invite us to step closer, to fill in the space’s stillness by imagining the shadowy authors who once lived there. Wasn’t this why the Romantics liked ruins? Because they asked you to take that imaginative leap to render what was there before.

Visiting dead writers’ and artists’ houses is akin to the experience of reading itself: you walk through the past and through someone else’s life and space without becoming them. A gentle kind of ghosting, a kind of stepping into other shoes, ever so slightly intrusive.

In walking through dead writers’ houses, we understand that time and space do not coalesce.

From the age of nine, each September for twelve years I went to Charleston Farmhouse in Sussex, the country retreat of the Bloomsbury group. The house is nestled against the Downs, soft hills near the southern coast of England. It is one of those places I only know in late summer, meaning that for me it’s trapped in a permanent September haze. Last belt of the sun. Cows and bats. Stone heads watching you from across the pond. Perhaps this accounts for my attachment to the place, but I also believe it to possess an inexhaustible charm.

Virginia Woolf persuaded her sister, the painter Vanessa Bell, and Bell’s sometime lover, Duncan Grant, to buy the house in 1916 during the First World War. On arrival, Bell whitewashed over the blousey floral wallpaper inside and soon they began to paint and print the walls, door knobs, fireplaces. Bell decorated Grant’s bedroom; Grant decorated Bell’s bedroom (on the black wall beneath the window he painted a grey shaggy half-smiling dog to guard Bell at night and a cockerel to wake her each morning). It’s the kind of house that makes you want to paint your bath.

They painted, often inspired by their Omega workshops, intricate patterns, still lifes and murals, on fireplaces, bed frames, cabinets, baths, lampshades, tables, you name it. Over time, the house—which Woolf, T.S. Eliot, and E.M. Forster passed through; in which John Maynard Keynes (having an affair with Grant) penned some of his most famous economic theory; where Julian Bell, Woolf’s nephew, grew up before he was killed driving an ambulance in the Spanish Civil War—began to shape to its inhabitants. Plaster casts of the inhabitant’s ears are pinned to the wall in the studio, busts squat in fireplaces, a carpet from London is fitted in Clive Bell’s room since he inclined towards luxury. Charleston developed its own mythologies—the Picasso stashed in the hedge overnight, or the ghosts of the Bell children clambering out of the upstairs dormer windows and jumping into the lane, escaping the tensions simmering inside the house.

Today, time acts strangely in Charleston, and it is curious to walk through this slanted, by-gone world. The curators make a point of keeping visible curation to a minimum. They avoid putting up plaques, notices or ropes in the rooms. The curator’s job is to stop the tide of time, and such time-halting creates a charged atmosphere in the space; time-forces in conflict.

Mark Divall, the former gardener, lived in the Charleston attic with his whippet, Dogum, when the house was first restored and later when it opened to visitors. In the evenings, he told me, he would walk around the rooms “to stay connected. I was dealing with the garden and it’s important for the garden to look good from the house.” Charleston is a house of many windows, meaning that the house and garden are inextricably entwined. Mark’s genius was to craft the garden that exists today from Vanessa’s paintings, keeping the house within its frame.

Living in a house redolent of its past occupants: “You could hear the guided tours going round the spare room, people in the kitchen down below. Sometimes during the summer I’d go to the forest to get away. If I returned around nine o’clock, the house would have healed itself from the intrusion. Almost like the way a pebble drops into a pond and then five minutes later the water’s flat again.”

For Mark the spirit of the past inhabitants clearly lingered. “There was certainly a sense of them but it was never as near as a ghost. If I was with Sylvia, my partner, and we’d come back from a walk on the Downs when it was just getting dark and the house had closed, you’d look up at perhaps a light up in the attic that we’d left on, and there was a feeling—which may seem crazy—that we could be Duncan and Vanessa returning from a walk. It was a sort of twinning, if you like, of how they must have felt, because it was home to them, as it was, in a way, for me. Although quite a bonkers home.”

A twinning, a ghosting, a home that belongs simultaneously to the past and present. In walking through dead writers’ houses, we understand that time and space do not coalesce. Time tends to move faster than space. This is why Ben Lerner speaks of “time paused” rather than time past in Topeka School as the protagonist drives in adulthood around the suburbs of his adolescence. Why returning to my university town was like showing up on set when the play was over: everything looked the same but my narrative there was through. We lack words for this disjunct between time and place.

When this pandemic is over there are writers’ houses I’d like to visit, in the hopes of catching some beguiling insight.

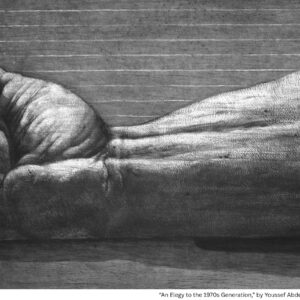

Virginia Woolf understood it. She illustrates the incompatibility of space with time in the slim central part of her novel To the Lighthouse. This section documents the war and the period following Mrs. Ramsay’s death. The swift actions of the characters’ lives are tucked into telegram-like parenthesis and the house takes over the narrative. The house is abandoned by the family, only the old housekeeper occasionally comes by. Woolf’s novel notices that people’s lives move at a faster pace than place. That places loom silently while our lives play out. Woolf understands too that our ghosts linger where we once lived:

“What people had shed and left—a pair of shoes, a shooting cap, some faded skirts and coats in wardrobes—those alone kept the human shape and in the emptiness indicated how once they were filled and animated; how once hands were busy with hooks and buttons; how once the looking-glass had held a face; had held a world hollowed out in which a figure turned, a hand flashed, the door opened, in came children rushing and tumbling; and went out again. Now, day after day, light turned, like a flower reflected in water, its sharp image on the wall opposite.”

I love the line “how once the looking-glass had held a face,” for it chimes eerily with the mirror and dressing table in the so-called spare room of Charleston which came from Vanessa and Virginia’s mother. Woolf writes of this very same mirror when she describes their mother’s death in 1895 in Moments of Being: “Lead by George with towels wrapped around us and given each a drop of brandy in warm milk to drink, we were taken into the bedroom […] I remember the long looking glass; with the drawers on either side; […] and the great bed on which my mother lay.” How our things outlast us, refer to us. Our relationship to our things continues even when we are no longer there.

So, seeing, for example, Dylan Thomas’s writing desk displayed, not in a museum but among the clutter of his writing shed on the Welsh coast at Laugharne, it is possible suddenly to conjure the wholeness of his person. An admired writer becomes someone with bad habits, doors they slammed, crockery they chipped, curtains they never got round to mending, trinkets they were sentimental about, tables they sat around into the night, views they loved, muddy boots they tramped into the boat house. Suddenly a pot of pens constitutes only one slice of the life they led.

When this pandemic is over there are writers’ houses I’d like to visit, in the hopes of catching some beguiling insight. In particular, the Amherst house in which Emily Dickinson wrote for so many years on her 18-inch desk; Pablo Neruda’s five-story house, La Sebastiana, in Valparaíso, Chile; the Brontes’ weather-beaten Haworth; and, above all, the exceptionally cool house Elizabeth Bishop lived in with her lover, the architect Lota de Macedo Soares, in Brazil.

Maybe the resonance of all these houses is contained best in Woolf’s description of Mrs. Ramsay’s room after she has died: “There were boots and shoes; and a brush and comb left on the dressing-table, for all the world as if she expected to come back tomorrow.”

Phoebe Hamilton Jones

Phoebe Hamilton Jones is currently taking a masters in Social and Cultural Anthropology at University College London. Her first degree was in English Literature at Cambridge where she was president of Cambridge PEN.