On the Particular Joys of Etymological Detective Work

Martha Barnette Explores the Shared Proto-Indo-European Origins of a Diverse Group of Modern Languages

I’m often asked which word is my favorite, but that’s like being asked to choose a favorite star in the sky. There are way too many, whether in English or other languages. If pressed, I usually say my favorite is mellifluous, which describes something “sweetly pleasing”—the sound of a flute, a supple writing style, a pleasant voice. Besides having a lovely mouthfeel—the tongue touching the back of the teeth, the lips coming forward before settling back with a hiss—mellifluous has an etymology as sweet as it is picturesque.

Mellifluous comes from Latin mel, meaning “honey,” making it a linguistic relative of molasses, marmalade, and the name Melissa. The ancient Greek word melissa means “bee,” and may be a combination of two older words that literally mean “honey-licker.” The last part of mellifluous derives from Latin flu-ere, meaning “to flow,” from the same family of other “flowing” words, such as fluid and fluent. Something mellifluous, then, in its most literal sense, is “flowing with honey.”

Mellifluous is a great example of what Ralph Waldo Emerson meant when he said, “The etymologist finds the deadest word to have been once a brilliant picture. Language is fossil poetry.” Or as the nineteenth-century essayist Thomas Carlyle put it, “The coldest word was once a glowing new metaphor.”

The languages spoken by nearly half of the world’s population…are thought to have descended from this prehistoric language.

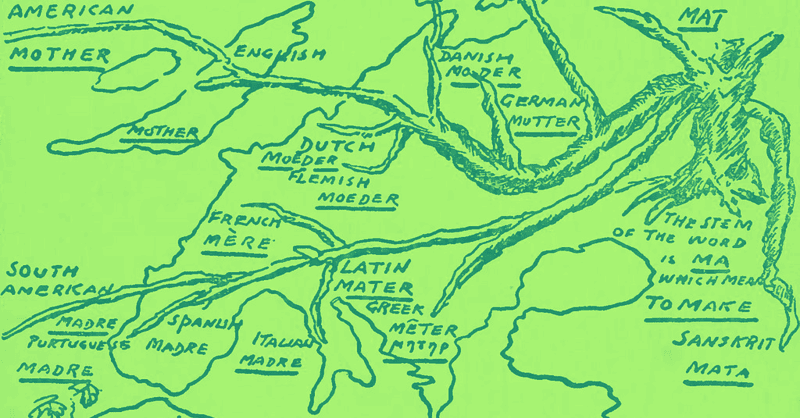

But just how do scholars dig up those linguistic fossils and discover those brilliant pictures within? One way is to compare related words in languages arising from a common ancestor, which brings us to the hypothetical mother tongue scholars call Proto-Indo-European.

The languages spoken by nearly half of the world’s population—including some four hundred million native speakers of English—are thought to have descended from this prehistoric language. Scholars have managed to reconstruct its fundamental elements by using comparative linguistics to identify common features and vocabulary in its descendants. Exactly where Proto-Indo-European began is a mystery. Some believe it arose six thousand years ago on the grassy plains of Central and Eastern Europe north of the Black and Caspian Seas. Others suggest earlier origins in Anatolia, the large region of what is now Turkey, bordered by the Black Sea to the North, the Aegean to the west, and to the south, the Mediterranean. Wherever Proto-Indo-European originated, its linguistic offspring spread throughout Europe, to Iceland and Ireland in the west, and eastward to India and what is now part of Chinese Turkestan.

Like taxonomists trying to classify the biological world into increasingly specific subgroups, specialists in comparative linguistics divide descendants of this parent language into eight large families of Indo-European languages spoken today that branch out from this root like a tree: Albanian, Armenian, Balto-Slavic, Celtic, Germanic, Hellenic, Indo-Iranian, and Italic. Those linguistic branches, in turn, divide into even smaller ones. English, for example, belongs to the Germanic group, which also includes German, Dutch, Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, Afrikaans, Icelandic, Scots, Yiddish, and a few others. In the Italic branch, only the Romance languages survive: Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian, Romanian, and Catalan, and several others such as Sicilian, Galician, and Dalmatian.

The Indo-European language group is just one of many, however. There’s the Afro-Asiatic family of languages spoken in northern Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and parts of Western Asia, including Egyptian and Somali, plus Semitic languages such as Arabic, Hebrew, and Aramaic. Other large language families include the reconstructed mother tongue called Niger-Congo, which gave rise to some 1,500 languages spoken over most of Sub-Saharan Africa, including Igbo, Yoruba, and Zulu. There’s also Austronesian, comprising languages that include Malay, Javanese, and Tagalog. The Sino-Tibetan language family comprises more than four hundred, including Mandarin, Burmese, and Tibetan languages.

Just how linguists divide all those languages into different families varies. Some of them sort the more than 7,000 living languages into 142 groups; others suspect the number of language families is closer to 400.

Not a word of Proto-Indo-European was ever written down, so how do we know that it, or something like it, existed? The answer is the strikingly consistent correspondence between various features among its descendants. These similarities are what Professor Latkovski meant when he compared the words for “foot”—Greek pous, Latin pes, Sanskrit padas, and their offspring. They are all cognates, or words that mean the same thing in different languages that arose from a common source.

Greek treis, Irish trí, and Welsh tri. The German version evolved as drei, and in Dutch, drie, reflecting a regular correspondence between d and t sounds that often appears among certain Indo-European languages. Something similar happens with English two and its various cognates in other languages, such as Spanish dos and French deux, and the kindred English words duo, duet, duel, and the double-tongued language app, Duolingo. Even the word dubious is a cousin to all these. Dubious comes from the Latin dubare, “to hesitate to make a choice between opinions or courses of action,” presumably between two of them. (Interestingly enough, the same idea of choosing between a couple of things is conveyed in the Old English word for “doubt,” tweó, a relative of Modern English two.)

Correspondences such as these are addressed in more detail by what’s called Grimm’s Law, a system of patterns named for the nineteenth-century linguist and folklorist Jacob Grimm—yep, the same Grimm who, along with the other Grimm brother, Wilhelm, published Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Building on the work of Danish philologist Rasmus Christian Rask, Jacob Grimm formulated a pattern of consonant changes, also known as the Germanic Sound Shift, which basically went like this: Indo-European p, t, and k morphed into Germanic f, th, and h, while Indo-European b, d, and g became Germanic p, t, and k; and Indo-European bh, dh, and gh became Germanic b, d, and g.

You can see some of these changes more clearly by comparing several Latin words to their long-lost English cousins. For example, the Proto-Indo-European root that produced Latin piscis or “fish” (as in the astrological fish Pisces) became English fish and German Fisch. The ancient root that gave us the Latin word pater, or “male parent” (as in paternity, patriarchal, and paternoster) became English father and German Vater, with its initial f sound.

Like detectives reconstructing a crime scene or archaeologists inferring the entire shape of a pot from a minimal number of fragments, scholars of historical linguistics figure out the earlier forms that must have given rise to words in many different languages and connect the dots between them. By analyzing remnants of these roots in various ancient and modern tongues, they’ve found links between English and modern languages as diverse as Russian, Persian, Danish, Polish, Hindi, Spanish, German, French, Portuguese, and Greek, and other modern languages as diverse as Nepali and Manx, as well as with ancient ones such Sanskrit, ancient Hittite, and Tocharian. Such correspondences offer a fascinating means of tracing human history.

Earlier, I mentioned choosing a favorite star. That’s as good a place as any to begin examining some of these puzzle pieces and how they fit together.

The Proto-Indo-European root for the word “star” produced words for this celestial body in several languages. Star came into English through the Germanic branch of languages, making it a cognate of Swedish stjerna and German Stern, as in Der Stern or The Star magazine and the name Morgenstern or “morning star.” All these words are also related to the Greek word for “star,” astēr, which gives us the similar-looking English name of the starry flower, the aster, and asterisk, literally, “little star.”

Greek astēr also shines within the word for those star-sailors better known as astronauts. The -naut, or “sailor,” in astronaut belongs to a whole fleet of nautical words from the same root. One of them, the Latin word navis, means “ship” and is the forerunner of English navy and navigate. The related Greek word for “ship,” naus, is preserved in our word for “ship-sickness,” nausea.)

It was once widely believed throughout Europe that stars produced an ethereal fluid that somehow influenced earthly affairs.

In the eighteenth century, for example, when an infectious fever raged throughout what is now Italy, the locals referred to it by the same name they had long used for any epidemic caused by the “evil influence” of the stars flowing in from on high. This outbreak spread far beyond Italy, and so did its name, influenza, or simply flu. The word influenza, or “influence,” comes from Latin for “flowing in,” which brings us back to all those other “flowing” words, like mellifluous.

I find all this oddly comforting, the way these connections reveal how others before us have puzzled over their own experiences and tried their best to make sense of them.

Let’s gaze into the night sky for just a bit longer. That luminous cloud of stars, the galaxy, takes its name from the Greek word gala, which means “milk.” The Greeks weren’t the only ones who imagined a milky splash across the sky. The ancient Romans also called it the via lactea or “milky way.” (The related Latin word lac, or “milk,” also appears in lactate as well as milky words in several other languages, such as Spanish leche, French lait, and that Italian espresso drink with steamed milk you might enjoy each morning: the latte.)

Now let’s turn our eyes to the Big Dipper, or Ursa Major, literally “the Big Bear.” Part of this constellation points to the North Star, found in the Little Dipper, or Ursa Minor, “the Little Bear.” The Latin word ursa gave us ursine, or “bear-like” and the feminine name Ursula, plus the Spanish and French words for this animal, oso and ours.

In Greek, the same prehistoric root of these words evolved into arktos, or “bear,” which brings us back down to earth—and specifically, to the Arctic region surrounding the North Pole. The Greek word arktikos literally means “of the bear” and alludes to the region “of the Bear constellation,” that is, “the north.” The Arctic is the home of Ursus maritimus, or literally the “maritime bear,” more commonly known as the polar bear. Part of that region is also home to Ursus arctos horribilis, the grizzly whose last name isn’t that hard to figure out. And of course, the related Greek word antarktikos, or literally, “opposite of the bear,” gave us the name of the place penguins call home, the Antarctic.

All these connections, hiding right there in plain sight—if only you know where and how to look.

I find all this oddly comforting, the way these connections reveal how others before us have puzzled over their own experiences and tried their best to make sense of them, to divide the world into manageable pieces and give all of those pieces names. In other words, we’re not alone. Our predecessors reached for metaphors to try to make the world legible to themselves and to each other. Over time, the words they created have tumbled and jostled against each other, evolved, grown appendages or lost pieces of themselves, developed new meanings and uses, and spun out far and wide.

For now, one more favorite word: vestigium. The Latin word vestigium means “footprint,” which is useful to know, because by investigating the roots of words, we discover vestiges of the past.

Did you see what I did there? Latin vestigium left footprints of its own in not one, but two, English words in that sentence. Right there in plain sight. Alas, etymologies don’t always reveal themselves so clearly. The origins of many words are simply lost in the mists of history, a disappointment that lexicographers record with the frustrating notation origin unknown, or orig. unk. Not very mellifluous, is it?

__________________________________

Excerpted from Friends with Words: Adventures in Languageland by Martha Barnette. Copyright © 2025 by Martha Barnette. Published and reprinted by permission of Abrams Press, an imprint of Abrams Books. All rights reserved.

Martha Barnette

Martha Barnette is a longtime journalist, dynamic public speaker, and co-host of the popular radio show and podcast A Way with Words. She holds an undergraduate degree in English from Vassar College, did graduate work in classical languages at the University of Kentucky, and studied Spanish in Costa Rica. Barnette is the author of A Garden of Words, Ladyfingers & Nun’s Tummies, and Dog Days & Dandelions. She lives in San Diego, California.