On the Paintings of Pieter Bruegel

Toby Ferris Considers Winter Landscape with a Bird Trap and Census at Bethlehem

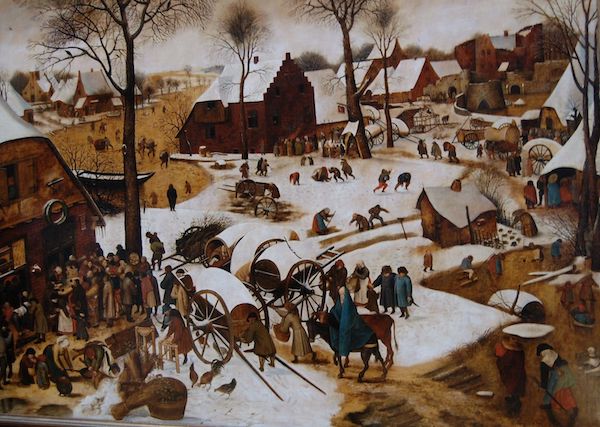

The census is an unusual subject. Pieter Bruegel has painted one of the culminating moments of bureaucratic life. Bureaucracy is the science of docketing the routine comings and goings of existence—births and deaths, taxes paid and taxes owing; it is a rolling program of work, one without end.

A census, however, is a one-off. It is a flourish of the bureaucrat’s art. You do not merely keep the ball of a census rolling: it wants planning and execution. It is, properly speaking, a project, a projection of bureaucracy. And it has an end: a Domesday Book of taxable, pressable souls.

From a distance—to the administrator or historian—a census is an exercise in control and power, not always pleasant, but always impressive in its way, like a datastream ziggurat or Hoover Dam. Seen close to, however, it pixilates into a sequence of inexact iterations. The bureaucratic ground troops do not mechanically fill in blanks. They have to keep a weather eye cocked on the confusion of crowds, have to sort quickly, roughly (there are only so many categories) but accurately. They have to fix a point in time where there are no points in time.

Bruegel’s Census at Bethlehem therefore depicts a world in transformation. The census is drawn through the village, through that mess of humanity at the inn door, like the carding of wool. The stream of individuals passes back and forth over the frozen river: people come in nebulous and free to have their names written down in a book, their existence validated in ink; they go out docketed and numbered, but also informed, no longer unlicked stray lumps of humanity but named individuals, with a location and an occupation and a marital status, enjoying a spark of existence beyond their own clay.

“Census at Bethlehem,” Pieter Bruegel, 1566.

“Census at Bethlehem,” Pieter Bruegel, 1566.

How, then, to number the paintings which hang in this room? How to enter them on the spreadsheet?

On an adjacent wall to the Census in Brussels is the Winter Landscape with a Bird Trap, a small sepia painting. Little figures skate on the frozen river, or huddle over their game of curling. On the bank, under a tree, a trap is set for birds: a heavy assembly of planks (in construction, not unlike the panel it is painted on) is propped up on a stick, a lure of crumbs beneath it; from the stick, there is the merest trace of a taut string leading into a house on the left of the panel.

Snatch the stick from under the planks and you might catch a bird or two, just as the painter of panels, ever watchful, might catch and trap a soul, or a village of souls. Snatch the ice from under those skating children, and you might drag one or two down. The birder, the painter, the Devil are always watching, always waiting.

Some are well-heeled, clearly not village folk, returned from the city for family weddings, to partake again, briefly, of the drunken, cavorting rhythms of village life.

The skaters and the birds are linked by two stylized black birds in the foreground. They are the same size in real terms as the skaters, the same tonality also; they could be mistaken at first glance for skaters.

Birds and skating villagers live a similar existence: birds have wings and skaters ease along at great speed; both are in danger, both seem at liberty. The birds could fly away, live in the woods, while the villagers could slide around that bend in the river and be gone in minutes, never to return. But the ice will melt and the villagers will remain. Winter birds, too, are territorial. All are rooted here.

Including Bruegel. Bruegel might have skated around that bend and away, to Antwerp, to Royal Brussels, to Rome and Naples and Calabria. But he came back. According to Karel van Mander, who included, in his 1604 Schilder-boeck, or Book on Painting, brief lives of the great Netherlandish painters, Bruegel frequently visited the villages around Antwerp and Brussels in disguise, infiltrating festival and kermis (a kermis—from “kirk mis” or “church mass”—being the annual festival held in honor of the village church’s named saint), observing but unobserved.

His panels are littered with figures standing on the edge of crowds, watching. Some are well-heeled, clearly not village folk, returned from the city for family weddings, to partake again, briefly, of the drunken, cavorting rhythms of village life.

One way or another, in paint as in life, this was Bruegel’s world.

Bruegel’s Bird Trap was a popular subject. There are at least 125 known and documented copies.

But what is a copy? If I were to take out paint and easel now, and run up some version of my own, would that constitute a copy? Number 126. Mark it down. At what point does the painterly spore of Bruegel peter out to blank snow? When can we say that the code has replicated itself into muddy, unrecognizable progeny, into mass reproduction?

On the wall opposite the Census, there is a large canvas, an Adoration of the Magi. This is not generally attributed to Bruegel, but may be after a lost composition, like the Icarus. It is in watercolor, an unusual medium for Bruegel. There is a tempera Blind Leading the Blind in Naples, and a Misanthrope; there is The Wine of St Martin’s Day in Madrid; otherwise it is all oil, all panel.

The canvas is badly damaged. Who knows how many panels have been lost over the years, painted over, chucked in skips, on bonfires. Van Mander mentions two versions of Christ Carrying the Cross (one remains); a Temptation of Christ, with Christ looking down over a wide landscape; a peasant wedding, in watercolor, with peasants giving presents to the bride; and one other watercolor in the hands of the same collector, undescribed. We know of others, gone missing. A crucifixion. A miniature Tower of Babel. The first in the sequence of The Months (April/May).

Whatever Bruegel saw when he contemplated his own Bruegel Object is lost to us, a ghost configuration. Whatever might be vouchsafed to posterity from a life lived—in Bruegel’s case, a lot; in my case, as in most cases, nothing—is only very approximately indexed to that life. I have very little interest in biography. It is not Bruegel’s completeness that I am interested in but my own. But I am conscious that the dead panels stand whispering beyond my spreadsheeted ring of firelight, and no amount of conjuring will induce them to step forward. It is too late.

__________________________________

From Short Life in a Strange World by Toby Ferris. Copyright © 2020 by Toby Ferris. Reprinted courtesy of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Toby Ferris

Toby Ferris is the creator of “Anatomy of Norbiton,” a web-based series of essays on suburban life and universal failure, as seen through the lens of the art of the Renaissance. He lives and works in Cambridge. Short Life in a Strange World is his first book. http://anatomyofnorbiton.org/