On the Pain of Breaking Up with My Old Apartment

Adrienne Celt Tries to Settle Into Her New Home

When my husband and I bought our house, I went a little bit insane. I had just been informed I didn’t get a tenure-track teaching job in Minnesota, and though I was disappointed I was also happy to get to stay in Tucson, the city we’d been living in for the previous two years and had come to love. We decided to formalize our new commitment to the town by becoming homeowners, and were lucky to have enough money saved to do so with relative speed: which turned out to be a mixed blessing, at least in terms of my personal psychology.

Shopping for a house doesn’t have to be problematic—in fact, it can be a lot of fun. You make a long list of qualities to share with your realtor, including the price of a property, location, aesthetic, and your personal tolerance for renovations, and then you start going to open-houses or doing private walk-throughs while the current owners are away. You get all the fun of imagining 20 new lives for yourself, paired with the anonymous Schadenfreude of judging someone else’s taste. “No,” you tell your realtor. “I certainly wouldn’t have put a wall there,” as if you had ever before in your life considered where a wall should go.

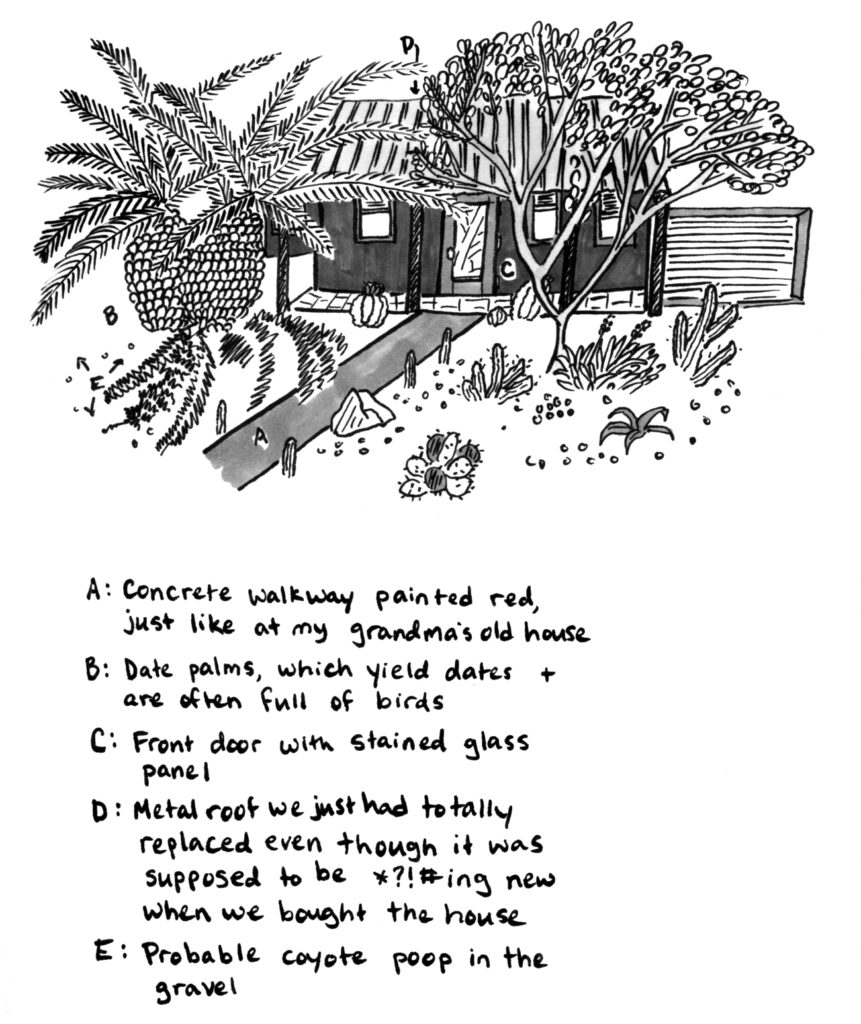

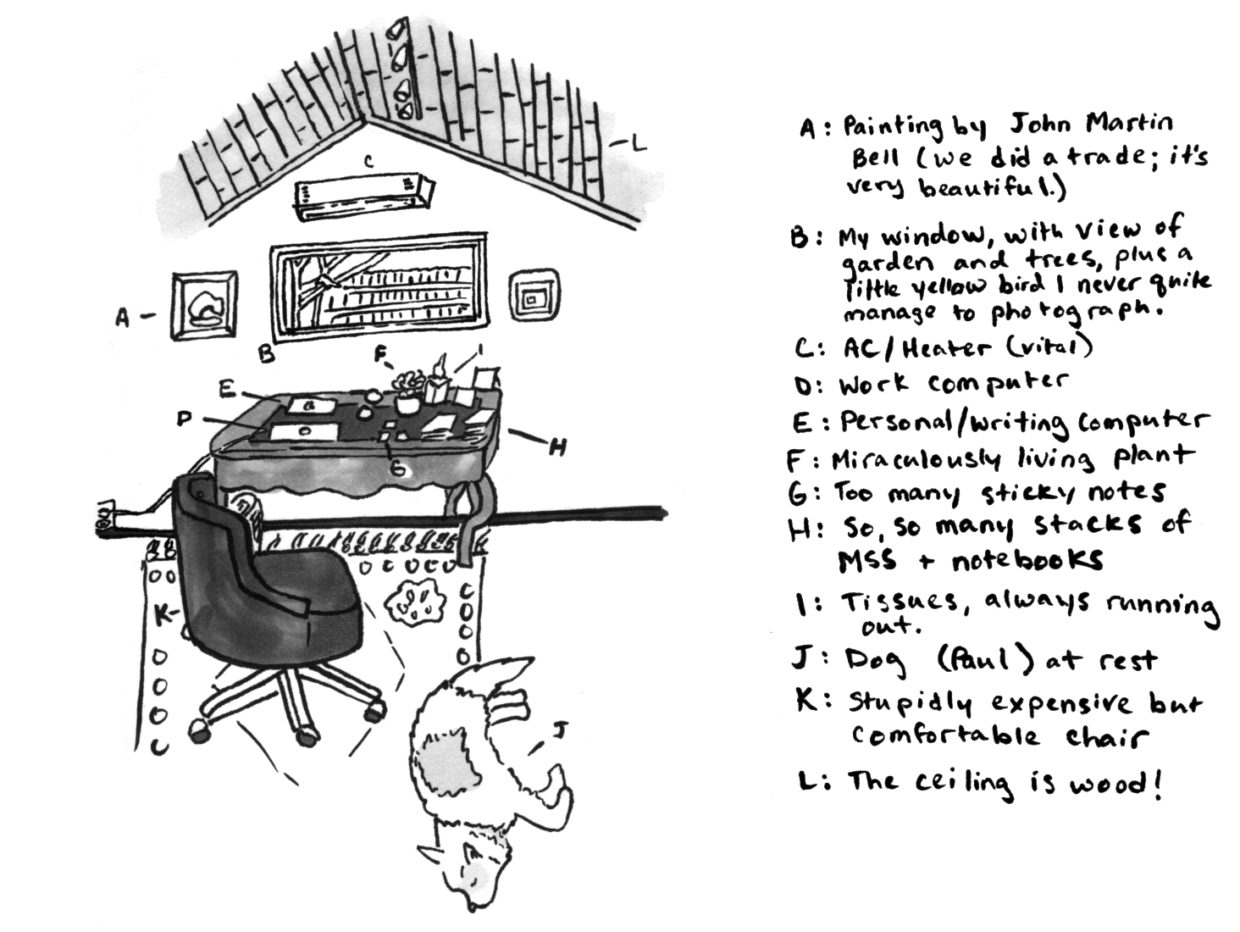

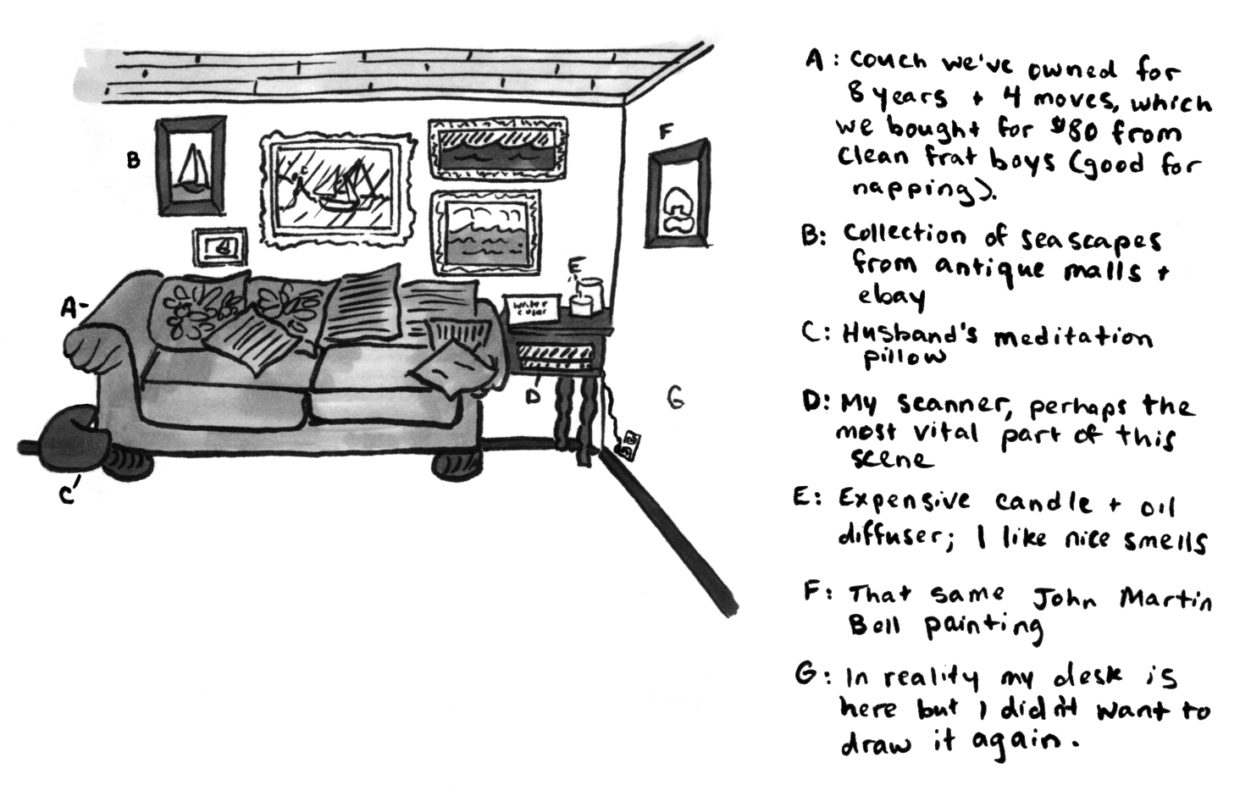

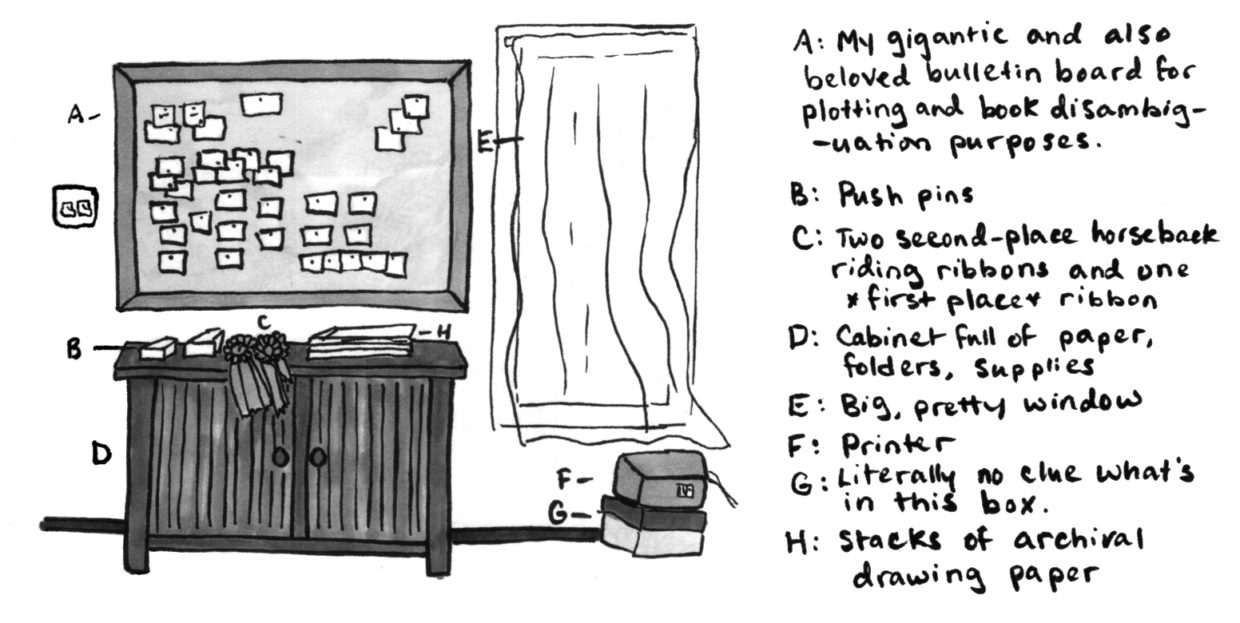

All illustrations by the author.

All illustrations by the author.

But then, if you’re serious, you have to start actually making decisions. After some handwringing, my husband and I chose a house well within our price range, in a previously-agreed-upon area of town, and made an offer that was accepted. It was a nice house, and we congratulated ourselves on completing the process with such grace and equanimity. Then I began to hyperventilate.

As it turned out, some of my relief at staying in Tucson involved my attachment to our old neighborhood, which was a seven-minute bike ride from downtown and full of 1880s adobe construction. It was a hipster neighborhood, and it was small, which meant it wasn’t particularly affordable; we chose a more suburban area in the middle of town (and if these sound like contradictions in terms you haven’t spent enough time in the southwest), where we could get a beautiful house with a little more square footage for our money, including a garage out back which we planned to renovate into a writer’s studio for me once the dust had settled.

Once our offer was accepted, though, I could no longer see the many good things about the house that we now owned. It was farther from our favorite breakfast place, farther from my yoga studio, closer to the university (and thus more proximate to legions of undergraduates), less historical, more work. The roof would eventually need to be replaced, and the yard was beautiful but unwieldy; a shock, considering the only plants I’d previously kept alive were in an herb box at our apartment. I remember telling my husband I wanted to back out, and then refusing to do so when he reluctantly agreed because I realized I was being nuts. I remember crying in the car, and feeling like no one was listening to me, like I couldn’t get out.

In hindsight, I can see that the perception of being trapped is not, for me, a completely unusual reaction to a major life transition. No matter how often my husband told me—or, for that matter, I told myself—that I would get used to our new neighborhood and figure out new routes to walk the dog, I couldn’t stop mourning what we were leaving behind. The nearby diner (which would be replaced by a different diner); the view of the small southern mountains (supplanted by a better view of the larger, northern mountains); the lovely courtyard of our ancient apartment complex, where we sometimes let our dog run around with his best-friend dog (our new house had an actual, private yard of course, which the dog was obsessed with immediately). All these things would be lost to me, I felt, and with them something less tangible might slip away too. My sense of freedom, and luck. My life’s nimble charm.

I’d like to say that I calmed down before the actual move, but I didn’t. I just chose to carry on because the alternatives were all harder and more frightening. We paid movers to bring in our hundreds upon hundreds of books, and bought new furniture to place those books on. I decided to re-watch all of The West Wing, since that was something I’d done incidentally in every home I’d had so far. One weekend, my husband, my mother-in-law, and I spent hours organizing the kitchen so that we could always find what we needed in a pinch: a system I had no faith in for some reason, but which turned out to work. Eventually, through small changes of this kind, I felt better, though it took time: I had to treat the move like a breakup, refusing to visit our old neighborhood for several months. Our house slowly came to seem almost good again, almost as good as it had seemed when we decided to buy it.

The one thing that was still outstanding, though, was the studio—or lack thereof. Our new spare room was too small to house workspaces for both my husband and I, and anyway we wanted to put a futon in there for guests. In the meantime, I was working in the sunroom, and the garage housed a few old boxes and not much else. But I couldn’t accept spending another huge chunk of cash on something I wasn’t sure would make me happy. What if we renovated the garage, and I decided I would’ve preferred to spend that money on a month in Japan? What if I lost my job halfway through, and we needed the financial cushion? With the memory of my self-inflicted house-buying trauma still so fresh, I was hypnotized by all the possible futures spinning out in my mind.

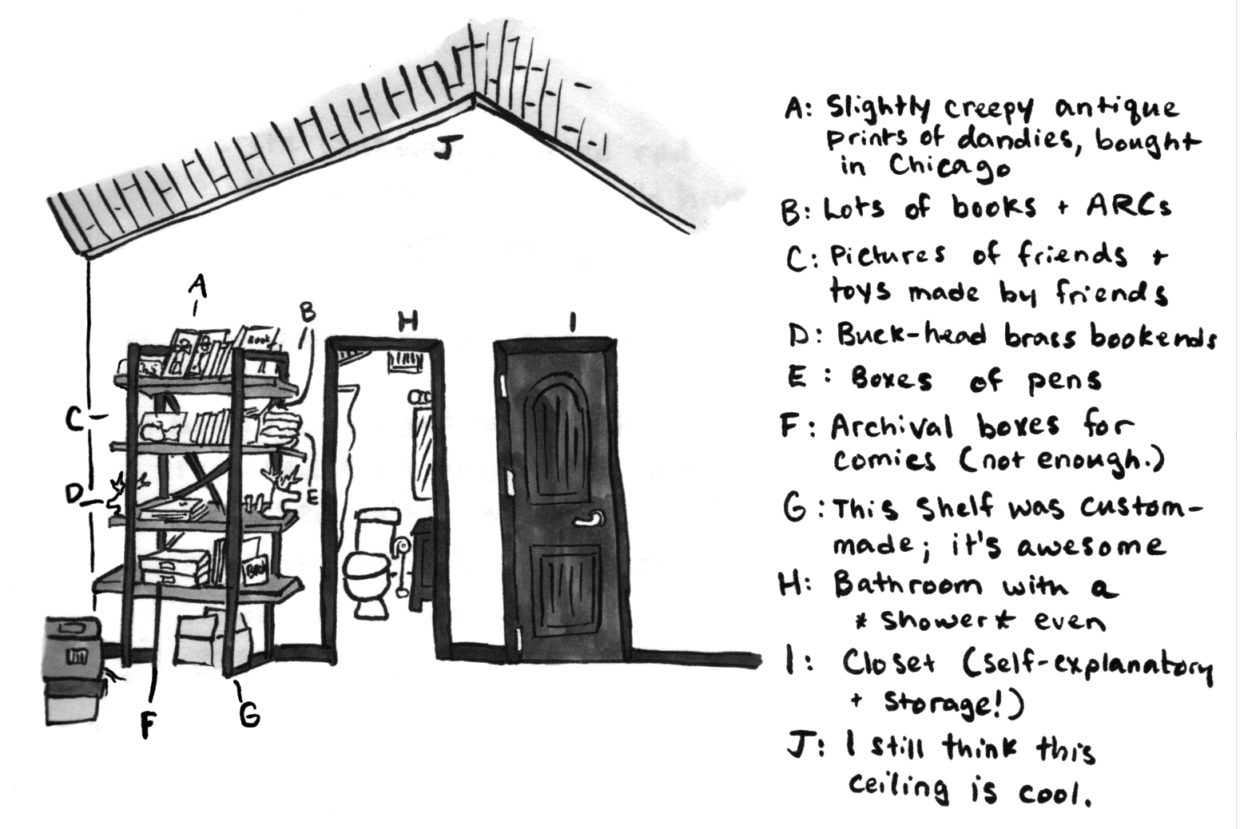

At last, with some gentle nudging from my husband, we met with a few contractors and found one we trusted, who said he could do everything we wanted for a reasonable price. I steeled myself for several months of men coming and going through the backyard, digging up ditches to lay new pipe, tearing out the old insulation from the walls. The space was large enough that we were able to add a small bathroom and a closet for extra storage, and we put in a large new window over the area that would house my desk. The contractor kept wanting me to paint everything shocking colors, to “make it my own,” he said, but I convinced him to paint the walls a fresh white with a dark gray trim; to match our house, the ceiling is lined with wood panels, and sitting inside the studio now feels like being in a cedar chest. I added a rug (bought years before at an antique mall in Madison, Wisconsin—my husband’s hometown), a couch (from some unusually clean frat bros in Phoenix), a large desk, a bulletin board, a bookshelf. A gauzy curtain for the air conditioner to trouble in the summer heat. As soon as the renovation was complete, I walked in and felt a sense of recognition. I was here. I was home.

It’s meaningful to have a room of your own: a clean floor on which to throw tarot, a couch for naps when you feel overwhelmed. Walls to cover however you like—in my case, with seascapes that remind me of the ocean, which are a compromise I make between my childhood in the Pacific Northwest and my adulthood in the dry desert heat. The dog likes to sleep on the rug by my feet, and sometimes I lie down next to him, looking out the window, watching the birds. I’ve written a novel at my enormous desk, drawn dozens of cartoons, earned a living, and followed the path of my best and worst thoughts.

When we bought our house, I worried I was leaving some intuitive portion of my body behind in our old apartment. I cried as we gave the landlord back our keys, and before I left the bedroom for the last time I licked the wall, as if to consume it and carry it with me, a sort of spiritual pica. I loved that apartment, which we’d found by chance on the internet and signed a lease for sight unseen, and I think now that part of my fear about our new house was the idea that forming your own destiny by choice—picking it out like wallpaper, or a pair of jeans—was unseemly in an uncertain universe. I don’t think that anymore. Forming a plan, seeing it through: these are also beautiful and creative acts. These are also gifts, though they make the universe no less uncertain.