On the Outsize Power of the Short Story (AKA the Genre of “High Genius”)

Daphne Kalotay Reminds Us of the Value of Short Fiction

Story collections are the country cousins of the American publishing landscape, tolerated with benevolent condescension while their authors are urged to produce that more glamorous product: novels. A novel might find a broad audience, even become a bestseller! Whereas—as a writer friend once put it—“You tell your agent you’ve written a story collection, and she looks at you like you farted.”

Yes, stories often represent a first foray into fiction—but for many authors, they remain the preferred genre. Gina Berriault, whose collected volume Women in Their Beds won the National Book Award shortly before her death, confessed that, were it not for pressure from her publisher, she never would have penned her novels. It’s the rare few, like Canada’s Alice Munro, recognized with a Nobel Prize in 2015, who go global based on their short fiction.

Danielle Evans, who followed her lauded debut collection not with a novel but with the 2020 award-winning novella and stories The Office of Historical Corrections, has said that the multiplicity of the story form allows her to “shape-shift,” freeing her from being “the voice of your community, which is a fraught place to be speaking from.”

Others who prioritize stories find themselves celebrated on a smaller, if no less notable scale. All three books by Amina Gautier, winner of the PEN/Malamud Award for Excellence in the Short Story, are prize-winning collections, each issued by an independent or university press.

Edgar Allen Poe declared stories—in describing which forms of writing “best fulfill the demands of high genius”—second only to poetry.Still the assumption persists: readers aren’t interested in stories. If a collection is fortunate enough to be picked up by publisher, the advance is usually small—and without a significant investment, there is less pressure to earn it back, meaning less money or attention from Marketing, meaning that fewer readers hear about the book, meaning fewer people buy it… supporting the conviction that short stories don’t sell.

Really there are readers and writers for whom short stories represent perfection. Perhaps the first to formulate a theory of the short story, Edgar Allen Poe declared stories—in describing which forms of writing “best fulfill the demands of high genius”—second only to poetry:

We allude to the short prose narrative, requiring from a half-hour to one or two hours in its perusal. The ordinary novel is objectionable, from its length … As it cannot be read at one sitting, it deprives itself, of course, of the immense force derivable from totality. Worldly interests intervening during the pauses of perusal, modify, annul, or counteract, in a greater or less degree, the impressions of the book. But simple cessation in reading would, of itself, be sufficient to destroy the true unity. In the brief tale, however, the author is enabled to carry out the fullness of his intention, be it what it may. During the hour of perusal the soul of the reader is at the writer’s control. There are no external or extrinsic influences—resulting from weariness or interruption.

Of course, Poe’s readers were not reading on smartphones constantly bleating notifications—yet his concept of “unity of effect” (sustaining a tonal, emotional consistency for an entire work) remains apt.

Short stories also tend to translate more satisfyingly to full-length film format. While adaptations of our favorite novels often disappoint—entire characters or plotlines necessarily omitted or compressed—emotionally complex short stories like Annie Proulx’s “Brokeback Mountain” or Alice Munro’s “The Bear Came Over the Mountain” become fully contained, without losing their profundity, in the hands of Ang Lee and Sarah Polley (Away From Her). And with space to fully display, even expand upon, their brilliance, more conceptual stories, like Philip K. Dick’s “Minority Report,” Daphne du Maurier’s “Don’t Look Now,” and Ryūnosuke Akutagawa’s “In a Grove” (Rashomon) become even more vibrant on screen.

Educators like myself also appreciate short stories as compact teachable units that can be thoroughly discussed in a single class session. It is in this mode—as both author and teacher—that I have come to note, over the years, the fiction collections and individual stories that deeply move not only me but also my college students.

When I consider the qualities these “favorite” works have in common—beyond students naming them as their favorites—I find myself thinking of a book I once bought based purely on the cover. It was a poetry collection by Les Murray called Poems the Size of Photographs. The cover image, a sepia tint outdoor photo, showed two jolly looking men from another era (perhaps father and son?) bearing huge, strange, even more ancient-looking axes. The combination of the men—their relationship, their expressions—and the axes made the photo arresting and odd, and the book itself was very small, square rather than rectangular, the poems, too, small on the pages.

The title suggested that even brief “snapshot” poems could encapsulate whole worlds while simultaneously interrogating them—urging us to contemplate their possible meanings, just as the cover photo had. And while I am not suggesting that the most powerful, memorable, or resonant short stories are necessarily “snapshots,” the title of that little book returns to me as I try to put into words what I mean when I consider the salient qualities of the short fiction that my students and I return to.

I mean that the stories in those collections, too, feel “the size of photographs.” There is a sense that one might regard them again and again and each time discover something new: a narrative that expands while preserving that essential air of mystery.

In the same way that a photograph asks us to dive, even momentarily, into a world and perhaps emerge with new questions, a good story conveys a sense of more going on in the background, more to be discovered. We choose to return to them because something in them—honesty, clearsighted wisdom, a sense of humor, surprising turns of phrase, depth of character—lingers, expands. In their indelibility, they become “big” as photographs—or, I might add, as novels.

__________________________________

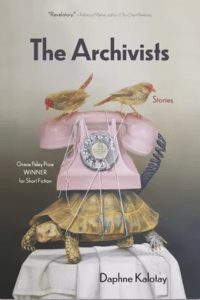

Daphne Kalotay is the author of The Archivists: Stories, available now from Northwestern University Press.