On the Origins of White Europeans’ Bigoted Fascination with Skin Color and Racial Hierarchy

Olivette Otele Considers the Historical Representation of Black People in Art and Fiction

Gender and race became such a contentious place of fear in medieval Europe that a need was felt to neutralize anything that was perceived as a threat to gender norms or racial hierarchy. Europe’s involvement in colonial slavery reinforced prejudice and saw a rise in debates about race, the origins of skin color, and people of African descent’s intellectual abilities.

Napoleon Bonaparte’s aversion towards Joseph Boulogne should be put into the much broader context of attitudes about African Europeans at the time in France. Napoleon was not the only one to have set views about black people in France and in the colonies. The increasing concern over gender and race hardened positions on and views about people of African descent. When they were out of sight, the question of race was really the colonists’ problem.

However, theories about the reasons for differences in skin tone had already started to intrigue European naturalists and other scholars, as we have previously noted. Colonial slavery brought about renewed interest in and new hypotheses about those racial differences. Race and gender dynamics also played out very differently in different places, with views on the Other varying from France to Senegal or Ghana.

The origins of Africans’ skin color troubled 17th- and 18th-century naturalists and philosophers. In 1665, Italian doctor Marcello Malpighi contended that there was a coloring system below Africans’ skin. In 1684, doctor François Bernier suggested that the sun might be responsible for darkening the skin of North Africans, Indigenous Americans, and South Asians, but that the skin color of sub-Saharan Africans was hereditary.

By the first half of the 18th century, others held the same views but wanted them to be scientifically tested. Among such people were Dutch botanist Frederik Ruysch and French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon. The latter suggested that to verify these hypotheses, one could take an African up to Denmark, isolate him from the rest of the population and see whether he lost his color. Meanwhile, American surgeon and anthropologist Josiah Nott was suggesting that the further north one traveled, the fairer people’s skin got and the cleverer populations became. Ironically, if one followed that logic, Indigenous populations of the Arctic region were the cleverest communities on earth and not, as Nott suggested, white Europeans.

Although the idea of a color change, or the possibility that black people might not be black under certain circumstances, was incongruous, the theory was not novel to 17th- and 18th-century scholars. Such ideas have been circulating for centuries. The Greek novel Aethiopica, written by Hellenised Syrian Heliodorus of Emesa around 3rd Century CE, was found in the 15th century and translated into several languages.

The story is about Chariclea, the daughter of King Hydaspes and Queen Persinna of Ethiopia, who was allegedly born white because while in the throes of passion her mother looked at a painting of Andromeda. Ashamed, Persinna hid Chariclea and then sent her away. She ended up in Egypt and later Greece, where she met Theagenes. The story ends with Chariclea being reunited with her parents.

Karel van Mander III’s series of paintings about the meeting in court, with Chariclea trying to prove her affiliation to her parents, brings to the surface notions of transmission, gender and representation. In Mander’s paintings, black characters are richly clothed and beautifully positioned. It was expected that African courts were as sophisticated and colorful as those in Europe. Mander’s work was deemed outstanding by the 18th-century educated elite.

Although a work of fiction, Heliodorus’s novel contributed to the idea that wealthy Africans were, at some time in the past, Europeans’ equals. Heliodorus’s own origins troubled the strong delineation that existed between Greece and those who were simply called “non-Greeks.” It was believed that intercultural dialogue could transcend race in many cases. Black people could have white children. Andromeda herself, an Ethiopian princess, could have been black, as has been suggested in numerous literatures. The color of Chariclea’s skin could therefore have been a fluke. In her work on Aethiopica, Marla Harris addresses these questions by quoting Elaine Ginsberg: “when ‘race’ is no longer visible, it is no longer intelligible: if ‘white’ can be ‘black,’ what is white?”

French merchants and Enlightenment thinkers struggled with the notion of equality when it was applied to Africans and people of African descent. In 1716, the mayor of Nantes Gérard Mellier, discussed in the previous chapter, contended that Africans were prone to “theft, larceny, lechery, laziness and treason” and that they were “only fit to live in servitude, and to be used in the labors and in the cultivation of land on the continent of our American colonies.” A few philosophers were of a similar opinion.

Although he had displayed ambiguous views about Islam and the Quran in his 1736 play Fanaticism, or Mahomet the Prophet, French philosopher Voltaire changed his mind 20 years later and enthusiastically supported trading connections with the East in his Essai sur les moeurs et l’esprit des nations in 1756. No such change of heart was to be found with regards to enslaved people, or Africans generally. Despite his criticism of the treatment of the enslaved through the figure of the “Negro of Surinam” in his 1759 satire Candide, Voltaire had trading interests in the colonies. Those with vested interests in the slave trade tended to try to justify enslavement. The Marquis de Chastellux, one of Voltaire’s admirers, wrote in his Voyages dans l’Amérique septentrionale that the negroes’ “natural insensibility” played a part in mitigating the pain they might feel while working on the plantations.

One could say that if beauty is in the eye of the beholder, so is fantasy.Napoleon’s views on black people were based on the evolving situation in the colonies. In 1799, he promised to the “brave black men of Saint-Domingue” that the abolition that had been granted in 1794 would be maintained. People such as Admiral Lacrosse who were ready to launch expeditions against the rebellious colonized in Saint-Domingue were amongst Napoleon’s inner circle.

Using Yves Benot and Claude Wanquet’s work, Erick Noël has demonstrated that Napoleon’s opinions about black people were complex. For instance, he wondered how freedom could be granted to Africans, yet also viewed them as people who had no respect for property rights. He was also ready to grant more powers to Toussaint L’Ouverture, a leader of the Haitian Revolution, so that Haiti could take part in the fight against Britain. Pragmatism seems to have prevailed when it came to colonial matters, but not entirely.

Napoleon had married Joséphine de Beauharnais in 1796. She was born Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie in 1763, the daughter of a wealthy plantation owner whose family had been trading in enslaved people and sugar for centuries. She was the eldest child of noblewoman Rose Claire des Vergers de Sannois and aristocrat Joseph-Gaspard Tascher de La Pagerie. Joséphine spent her childhood in Martinique. She married Alexandre de Beauharnais, who was later killed by the revolutionaries. She then married Napoleon but was unable to have children with him, even though she already had children from her first marriage.

Napoleon eventually divorced her in 1809. Prior to that, particularly between 1799 and 1801, she had been influential in the decisions he made regarding French colonies of the Americas. She had fiercely defended her family tradition regarding the slave trade, and the potential loss of colonies was perceived as a real threat to white planters’ social and economic interests. The first French abolition of 1794 had been a blow to them. Napoleon’s views on people of African descent have been attributed to her influence.

We rightly associate the history of African Europeans with journeys across the oceans and attempts to adapt to new environments in Europe. The stories of black figures have dominated European arts for centuries. However, the representation of black people in the arts changed significantly between the 17th and the end of the 19th century. The exoticization of black bodies still played a part in their representation, but a power relationship was also on display in many paintings. From the household of a wealthy nobleman or merchant in London to the salon of a trader in Nantes, Seville or Lisbon, black figures were a sign of wealth.

The black page in William Hogarth’s Marriage à la Mode (c. 1743) was typical of art across the rest of Europe; such representations were as common as paintings of renowned black models. In all cases, the European gaze was as much an anthropological attempt to normalize societal changes as it was a journey fantasized by the artist and the audience. From the frescos of African figures dating back to the second millennium BCE found in Crete to 19th-century paintings of female black models, one could say that if beauty is in the eye of the beholder, so is fantasy.

__________________________________

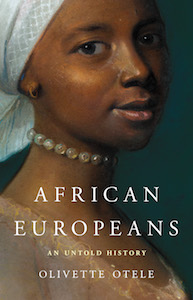

Excerpted from African Europeans: An Untold History. Used with the permission of the publisher, Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of HBG Publishing, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. Copyright © 2021 by Olivette Otele.