On the “Misogyny Paradox” and the Crisis of Heterosexual Coupledom

Jane Ward Wonders How Love Can Fit Into Patriarchal Ideas of Marriage

On a recent vacation with my partner, Kat, and our nine-year-old son, we strolled by the storefront of a touristy T-shirt shop. There were hundreds of T-shirts for sale inside the store, but a few, presumably some of the shop’s most popular, were displayed in the front window. One of the T-shirts hanging in the window depicted an image of a stick-figure straight couple on their wedding day: she is smiling, and he is frowning. The text below them reads, “Game Over.” A T-shirt just next to this one showed another stick-figure straight couple holding hands while the woman figure’s mouth is open, with speech lines indicating that she is talking. Next to this image, the same couple is depicted again, except the male figure has hit or pushed the woman, and she is falling down, headfirst. The text below reads, “Problem Solved.” I was walking, holding my son’s hand, when I noticed the T-shirts. I instinctively walked a little faster, hoping he wouldn’t see them. I was not ready for him to know—and for me to explain—that many people think it is funny when men dislike or hurt their wives and girlfriends.

How did we get here? Today, we generally agree that straight people are those who “like” the other sex. This attraction is often understood to include mutual desire for intimate, romantic, love-based connection. These are such basic, defining features of contemporary heterosexuality that it can be tempting to imagine mutual desire and likability as the long-standing forces that have driven most heterosexual coupling. But historical evidence dispels us of this fantasy and helps us to understand why it is easy to find examples, on T-shirts and elsewhere, of men’s simultaneous desire for and hatred of women—all wrapped together into one dysfunctional sexual orientation.

Across time and place, most forms of heterosexual coupling have been organized around men’s ownership of women (their bodies, their work, their children) rather than their attraction to, or interest in, women. Women were men’s property, slaves, and laborers, and women produced heirs to whom men could pass on their lineage and possessions. Women were the people with whom men had procreative sex, and women of privilege (wealthy women, white women, women of high status) were sometimes perceived as delicate and virtuous, in need of men’s protection and seduction (as in medieval and Victorian traditions of courtly and chivalrous love). But in none of these arrangements was “liking” women, or regarding them as men’s most logical and beloved companions, a requirement in the way that contemporary straight culture now presumes—or at least strives. Liking women was hardly understood to be a fixed or defining feature of one’s identity or “sexual orientation.”

In the United States, the notion of mutual likability between women and men did not gain traction among American sexologists and social reformers until the late 19th and early 20th centuries, just as the new concept of “the heterosexual” began to appear in medical textbooks. It took decades for both concepts—the idea that men and women should feel sexually and emotionally drawn to each other and that doing so meant that one was a heterosexual—to circulate widely enough that most Americans would have internalized them.

But this transition from woman-as-degraded subordinate to woman-as-worthy-of-deep-love was hardly smooth, nor is it complete.But by the late 20th century, they converged to create a new relationship ideal, modern straightness, which represented a dramatic rupture in the way that men had related to women for centuries. This campaign for love-based heterosexual relationships was undoubtedly a positive development, as it created tension between men’s violence against women, on the one hand, and the image of happy heterosexuality, on the other. But this transition from woman-as-degraded subordinate to woman-as-worthy-of-deep-love was hardly smooth, nor is it complete. This unfinished transition, and its central role in the tragedy of heterosexuality, is where we will begin.

The cultural expectation that men should like women, even as they are socialized into a culture that normalizes men’s hatred of women, constitutes what I call straight culture’s misogyny paradox. I first began thinking about the misogyny paradox when I read the extraordinary book Women with Mustaches and Men Without Beards, written by the feminist historian Afsaneh Najmabadi. Though Najmabadi’s focus is on nineteenth-century Iran, her book is a case study with global and contemporary significance as it highlights the intersections between misogyny, heterosexuality, and imperialism. In a nutshell, Najmabadi argues that as the new concept of heterosexuality began to circulate in the 19th century, and Iranians resisted one of its defining principles—that men should feel love for, and desire companionship with, women. This idea was a “hard sell,” Najmabadi explains, not only because it conflicted with long-standing beliefs about women’s subordination and degraded status (how could men love their inferiors?) but also because most Iranians had lived in gender-segregated and homosocial (if not homoerotic) environments in which intimacy was reserved for people of the same sex.

Najmabadi further explains that even heterosexual lust was looked upon with suspicion by some Iranian commentators, because it stood to threaten men’s patriarchal power: “If a woman can satisfy a man’s desire, he may become enamored of her, develop an affection bordering on love, and consequently, become subordinate to her.” And yet, under the imperialist influence of Europe, where new ideas about the superiority of heterosexual romantic love and the pathology of homosociality were rapidly taking hold, the Iranian state launched a cultural campaign to encourage men and women to direct their affections toward each other. This represented a dramatic shift in the way that men’s relationships with women were conceptualized, and it presented something of a paradox: “falling in love was what a man did with other men . . . [and] falling in love with women more often than not was unmanly,” but modern heterosexuality compelled men to engage in precisely this unmanly act.

Najmabadi’s book drew my attention to two seemingly obvious but rarely acknowledged points: (1) modern notions of heterosexuality require men to feel love and affection for women, the very population they have dominated and dehumanized for centuries, and (2) this has caused many problems for straight people, who are struggling to transition from the trauma and legacy of misogyny to something more authentically “straight”—if by straightness, we mean authentic and noncoercive heterosexual love. While Najmabadi’s focus was on Iran, there is evidence across the globe of men’s resistance to loving their wives and other women sexual partners and of the historically and culturally varied manifestations of women’s horrific subjugation by men in marriage.

The idea that men’s romantic or even sexual interest in women is threatening to patriarchy, or “unmanly,” may strike us as quite inconsistent with current understandings of heteromasculinity, yet there is ample evidence of the persistence of this view.The feminist scholar Gayle Rubin, for instance, famously offered a summary in her essay “The Traffic in Women,” in which she details how economic and kinship systems around the world have relied on women being “given in marriage, taken in battle, exchanged for favors, sent as tribute, traded, bought, and sold” among husbands and male family members. Some evidence of the misogyny paradox goes back centuries, such as scholarship on ancient Greece that documents that Athenian wives were regarded with contempt by their husbands and treated as servants within the family, while sexual relationships between adult men and boys were, in many cases, characterized by genuine affection and treated by Greek male society as a valuable method of preserving patriarchal power and strengthening male bonds.

Other evidence of the misogyny paradox comes from the 18th and 19th centuries, the same historical period of concern to Najmabadi. As one example, the historian Hanne Blank offers a telling account of heterosexuality in 18th- and 19th-century England and colonial America, citing the American preacher John Cotton’s concern that so many men “despise and decry [wives] and call them a necessary Evil” and noting that, for several centuries, men who loved women were perceived as “effeminate” or “cunt-struck.”

The idea that men’s romantic or even sexual interest in women is threatening to patriarchy, or “unmanly,” may strike us as quite inconsistent with current understandings of heteromasculinity, yet there is ample evidence of the persistence of this view. Indeed, my own earlier research looked closely at the links between white heteromasculinity and expressions of disgust or resentment for the object of one’s sexual desire—especially in the US military, in US fraternities, and in other male-dominated institutions in the United States. In some of these institutions, girls and women are so degraded that for straight men to express enthusiastic interest in them, as desirable humans rather than as bitches, whores, and abject receptacles for penetration, is to subvert their own masculinity (now sometimes called being “henpecked” or “pussy-whipped”).

Following the model set forth by Najmabadi and others, we now turn to the twentieth-century struggle for modern straightness in the United States and the concomitant emergence of a heterosexual-repair industry that capitalized on the difficulty of this project.

__________________________________

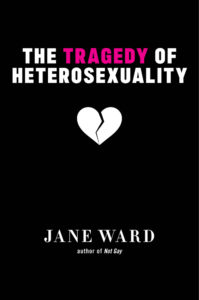

From The Tragedy of Heterosexuality by Jane Ward. Used with the permission of New York University Press. Copyright © 2020 by Jane Ward.