On the Little-Known Archives Keeping Civil Rights Activists’ Stories Alive

Suzanne Cope on the Importance of Keeping History Alive

On a hot September night in 1964 a bomb exploded under the bedroom of five-year-old Anthony Quin, youngest child of Mrs. Aylene Quin. Aylene was a single mother of four, restaurant owner, and voting rights activist in the small town of McComb, in southern Mississippi, deep in Klan country. It was her daughter Jacqueline’s ninth birthday, and after the bomb collapsed the front of the house where she and her brother were sleeping, you could see party streamers and birthday cake through the gaping hole.

This story—that 14 sticks of TNT were thrown at the house of “Mama” Quin, as she was known to local activists—is the reason her name is mentioned—if it is mentioned—in histories of Freedom Summer. I was drawn to her story because clearly she was considered a threat by the KKK, who were bombing local civil rights leaders with impunity. So why were there so few details about the work she had been doing around the county and beyond for a decade? I knew there was more to the story—of Mama Quin’s unique leadership, of the power of owning a restaurant and feeding activists during this hot and bloody summer—than was written about in popular histories of this time.

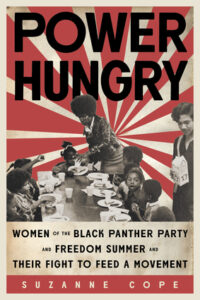

So on a cool and gray January day in early 2020 I steered my rental car down Summit Street in McComb, Mississippi. I had just begun research for my book Power Hungry: Women of the Black Panthers and Freedom Summer and Their Fight to Feed a Movement, and I wanted to have a sense of where Mama Quin had lived. From the screen of my laptop or the thick paper of library-bound books people remembered her as amazing. Hardworking. A force to be reckoned with. But I knew that by laying eyes on the house the KKK had bombed, and speaking with Aylene’s daughter or friends in the integrated library constructed with funds Aylene helped raise, would help me better understand and amplify her story.

Summit Street was, during Aylene Quin’s time in the 1950s and ‘60s, one of the central streets for Black commerce and social life. But other than a historical plaque, one would have only thought it another sleepy street in a quiet town. I had the address for her restaurant and tavern South of the Border, but only a few buildings had numbers. So I drove up and then back down the mile or so strip of low apartment buildings and single-story concrete block storefronts. The most activity was at the car repair shop, where three men, middle aged and older, were out front, inspecting a vehicle that had just pulled in. They had all watched me each time I passed their garage. And now, as I pulled in and stepped out, they regarded me with curiosity.

“Hello,” I smiled. “I’m in town researching Mrs. Aylene Quin. She owned a restaurant around here in the 1960s. Do you know where it was?” I pronounced her name A-leen, long A.

“Hey, LD,” the first man in coveralls, called to a gentleman who was about to get into his low pickup. “She here is looking for info on Mama Quin.”

LD walked over. “Mrs. Aylene Quin, huh.” He pronounced her name with a short a, like apple. “South of the Border was right there.”

He pointed across the street to a two-story apartment building set in the middle of an empty lot with scrubby grass and a gravel parking area. Then he smiled. “You know who you should talk to—my mother. She worked with Mrs. Quin when she was president of the NAACP back in the ’60s. My mama was the secretary. She’d tell you stories all day.”

*

Within minutes I was sitting in the living room of 90-year-old Mrs. Patsy Ruth Butler, surrounded by framed certificates of appreciation for her civil rights work and graduation portraits of her grandchildren. She told me stories about the men who kept watch for KKK bombings during the summer of 1964—of which law enforcement’s inaction allowed so many that McComb was called “the bombing capital of the world.” They would lay all night on the roofs of houses and churches, signaling to each other with flashlights and bird calls when a suspicious car drove by. She told me about visiting house after house with Mrs. Quin, canvassing for voting rights, most people too afraid of violent retribution to register. By the time I got up to leave she had invited me back to stay with her next time I was in town. Little did either of us know that the events of the year would not allow another trip.

I consider myself so lucky to have had the opportunity to visit McComb just weeks before the pandemic halted travel, made personal interviews nearly obsolete, and would have all but precluded the happenstance of meeting an activist like Mrs. Patsy Ruth. That same month I had traveled to Memphis to meet Cleo Silvers, the Black Panther Party member who lived in New York in the 1960s and early 1970s and worked the Free Breakfast for Children Program, whose story is the other narrative thread in Power Hungry. She and I went out to hear live jazz, cooked a small feast for a dinner party, and talked.

Our few days together took on a rhythm. I would bring coffee and pastries and Cleo would answer my questions and tell stories. By late morning we had a snack paused to listen to her favorite jazz show. She looked around her apartment—overstuffed sofa, stacks of books and magazines and CDs—and reflected that all of her apartments had always been set up similarly: a semi-circle of seating for people to gather and talk, art and music and ideas all within reach. The afternoon of the dinner party I drove us to three different stores for ingredients and we swapped recipes and ideas. Back at her apartment, one of us chopped while the other stirred the soup and roasted the vegetables, conversation moving between memories of childhood and meals she cooked for fellow Black Panthers.

Cleo, too, was first a name I had read in passing as one of the few named female leaders of the Black Panther’s survival programs, despite that the Party’s membership was around two-thirds female. Aside from a few renown women, why were so few stories told of female leadership making breakfast for children, leading door-to-door health care, and organizing tenants to take over buildings from derelict landlords? It was over the shared meals that memories bubbled to the surface; the time sitting around the table with other activists that ideas were debated and history recalled.

*

I’ll never know what my book might have looked like if I had not been able to take those two, important trips before the world all but shut down. But I can compare the kinds of research I was able to do in person versus what I was forced to do solely from my apartment more than a thousand miles away. While I had more long talks with Cleo (who continued her activism virtually, perhaps becoming even more busy as the internet extended her reach), and interviewed many other people who were perhaps even more amenable to Zoom in the current climate, I was also starting to better understand how some of the research I had done on the ground that seemed incidental, had an outsized effect on my understanding of Aylene and Cleo’s lives. Researching outside of more formal institutions was essential to getting closer to the knowing, especially of people and time and place where I am not endemic.

The term “archival silences,” which I heard first a few months into the pandemic, gave form to what I was already understanding: that there are stories left untold and undocumented—intentionally or not—that skew what we know and understand about history. Considering these silences includes asking: what or whose perspectives are not included in archives and historical collections of a time period, event, or place? It is unsurprising that the experiences of people of color, of women, the impoverished, and lesser educated have often been long neglected by resourced archives, even as many strive to bring voice to these silences.

While I understood that by giving voice to the women and those they worked with was working to rectify some of this, only in the inability to travel did I better understand the importance of researching in person—and the power of more informal and local archives and collections that are not the places many researchers tend to look, and certainly not readily available virtually. These collections are often languishing without resources, despite that their archival perspective can help write, and right, historical accounts—if they are preserved.

One such collection is owned by Jan Hilgas, who has rented a storage space full of documents related to Freedom Summer, and who told me in January 2020 that she was months behind in rent. Despite pleas to pertinent libraries, she has yet to find an institution who has the resources and desire to take this on. I also heard that a trove of documents belonging to C.C. Bryant, longtime McComb NAACP officer and friend to activists Medgar Evers and Robert Parris Moses, was lost in a fire before he could find them a safer home.

But the Black History Gallery is a success story, demonstrating what can be done to preserve these imperiled archives. A small museum in a house on a residential street not far from Mrs. Patsy Ruth’s house, the Black History Gallery was collected and run solely by ninety-something Hilda Casin, a retired local high school teacher. Inside, ornate side tables held photos of local activists, framed documents, and typed accounts of events of significance to the local Black community—perhaps honoring business leaders and praising the election of local officials. In one room there was a movie viewing area, with a library of documentaries and movies on Black leaders and history.

Writers must consider the collectors who are keeping these voices alive.In another room, that, fittingly, was once the dining room, there was a section dedicated to Aylene Quin. Collected were images from the local paper, personal photos and business promotion, and ephemera from her funeral. A photo on a promotional fan for her newly opened hotel has the image that, in my mind, best represents the version of the woman from the stories her loved ones told me: dressed fashionably in a long cocktail gown, laughing with two friends, a morsel of food in her hand. From that display I learned more about her family, her businesses, her community-minded work, than I could find in hours of online research over the months afterward. One poster honoring local civil rights workers led me to Curtis Muhammad, living in New Orleans, who had known Mama Quin well, and who I would meet over coffee a few days later, hearing stories not even Aylene’s daughter had known.

I’ve thought about the fate of this museum often during my research and was heartened to discover that it had a new online presence in June 2021. There’s now a board of directors, with names I recognized from my research and a website boasting of the “most comprehensive black history collection in the region.” Through local leadership, this precious archive has been saved.

*

My goal with Power Hungry was always to give voice to the almost-silenced activism of two women who had been long reduced to historical footnotes. Despite the challenges, I feel confident I succeeded. Perhaps I interviewed some people over Zoom who might not have been as comfortable with technology previously; perhaps spending less time traveling meant that I dug deeper into other available resources and came across the names of people I might not have otherwise spoken with. One kind of silence opened the space for another voice to speak.

And I have come to understand, more than ever, the importance of documents like the ones Jan Hilgas is hopefully still housing for thousands of dollars a year in her storage space; those include documents like the affidavit signed by Aylene about one of the many instances of harassment by law enforcement. There are many dozens more like that, all representing the experiences of someone whose story is being silenced.

Writers must consider the collectors who are keeping these voices alive. They make it possible to see the objects that Aylene touched and photos only shared among her family and close community; to hear stories from her daughter, about what it was like to be in a home that was bombed by white supremacists that hot September night; to understand the many ways that Mama Quin put her life on the line to fight for voting rights and equality, and why her work to feed activists and connect a community felt so threatening to the KKK. Aylene Quin is worth writing about because of what she did— not because of the violence committed against her.

__________________________________

Power Hungry by Suzanne Cope is available via Chicago Review Press.