On the Line Between Truth and Fiction When Writing About Your Family

Lee Matalone Navigates the Tricky Realities of the Most Personal Histories

There are always margaritas at these family reunions. I step through the door of my uncle’s house and within minutes someone hands me a frozen beverage in the same pink plastic glass, rim limed and salted, that I’ve been drinking from since I can remember. Kisses and hellos. The whizz and buzz of the sick-beige Oster blender. There used to be more bodies sprawled across these white couches and seated around this round table. Now, half the family doesn’t come to the reunion, and only hushed family drama takes up the extra lounge space. I exit the house.

The house sits seaside in Virginia Beach, a town that has always seemed like an afterthought to the higher-status beaches further South—OBX, Hilton Head. Recently, though, New Yorkers, realizing their own beaches have reached a saturation point, have discovered it and made their way down I-95. Now, high rises and fro-yo shops have replaced, the junky boardwalk shops that smelled dank and sweet, where my Uncle and cousins and I used to go to buy two-for-$25 t-shirts with shoddy screen prints of Bob Marley and American flags on them.

But the house is an oasis. This is still oceanfront. At the end of the deck, my cousin lies on the familiar white plastic chaise. She rises to hug me in the way that only she hugs, like something terrible has just happened or is about to happen, tightly and intentionally. She settles back onto the chaise, onto a towel damp from dew and sea. The fourth of July is the day after tomorrow. Everywhere beyond us, beyond the seawall, we can see brightly colored umbrellas, beach carts, kids and adult men throwing footballs, towels lined out and the first few feet of ocean filled with bodies. It is too much. And I know what she is about to say is coming because I have been hearing it from others, in various forms, for months.

In hearing more about the novel, my family has latched onto the superficial mirrorings to my, and by easy extrapolation, their own lives.

So your book, she says, mid-margarita, Will it reveal how you truly feel about me? Is it a scathing review of our money hungry relations?

*

This anecdote is a fictionalization. My cousin was not mid-margarita when she said this; rather, after my book sold, she sent me a series of messages on Facebook. Her actual comments were A little autobiographical there eh lol. omg am I in it? will you tell me how you truly feel about me gahhhhhh

But I didn’t feel like rendering our interaction that way. There is poetry in an overcrowded pre-holiday beach, a cousin on a towel damp from dew and sea, and not much in “my cousin, on Facebook Messenger, said eh lol.” Of course, I could have dug deeper to exhume the lyricism in this series of Facebook messages, a lyricism I can appreciate, but that is not how I’ve decided to depict that conversation here, for my intents and purposes. I witnessed reality and chose to manipulate it—for the sake of aesthetics, for the sake of narrative, for the sake of because-sometimes-reality-needs-some-tidying-up, some prettying up, some logic-ing up, because clean lines and logic aren’t often found in life itself.

In her 1955 essay “Place in Fiction,” Eudora Welty talks about the writer’s role in managing reality: “The business of writing, and the responsibility of the writer [is] to disentangle the significant—in character, incident, setting, mood, everything—from the random and meaningless and irrelevant that in real life surround and beset it. It is a matter of his [the writer] selecting and, by all that implies, of changing ‘real’ life as he goes.” Being a writer of a certain type of fiction, in other words, is about taking reality and making it make sense for the narrative at hand. Meaning sometimes a writer has to do a lot of altering to real things, real people, real stories; Meaning you ultimately disappear from the narrative even though your t-shirt remains on the bed in chapter four.

The truth about truth in my fiction is this: There is reality, and from that reality manifests a string of narrative digressions.

In hearing more about the novel, my family has latched onto the superficial mirrorings to my, and by easy extrapolation, their own lives. Oh, you wrote about your Mom, says my grandmother from 2,000 or so miles away in Tucson, a city that appears in my book. Well, no, I text clumsily. It’s fiction, the character is not my Mom rather my mother served as a sort of template for a woman who may on the surface look like my mother but is really nothing like her so that may be confusing but no it is not my mom it is fiction . . .

I wonder if this is something all writers who borrow from real life must go through, a unique hazing ritual for the literary set: queasiness, discomfort, and finally, welcome to the club.

The truth about truth in my fiction is this: There is reality, and from that reality manifests a string of narrative digressions that take the story further and further away from reality. These come in the form of small embellishments, factual alterations and out-right fabrications. A fact may be a seed for a narrative that grows into an altogether exotic, alien-looking flower.

I imagine this is how the writing process operates for many writers who work with reality. We observe something in the world and, like the opportunists we are, adopt and mold it into something we can use. The character I create may look like you, the ashtray on the coffee table one reminiscent of the one on yours, the bottom imprinted with the same creamsicle-colored Motor Inn emblem, but the person discarding a roach into that ashtray is a very different person than you, I assure you, because I cannot really know you. I do not live inside your head and can never know what you are going through when you take that joint between your fingers at three in the afternoon on a Tuesday, alone in your apartment. I can only imagine.

Part of the comfort of writing is being able to pretend that I can know what is going on inside another person when really that is such an impossible endeavor. Part of the comfort of writing is that I can, for a series of moments at a desk, pretend I know, when I know I will never know another person, not really. So when someone asks me about the realities in my fiction, I am thrown. I don’t know how to tell people that my characters are not them, to give them comfort that I am not setting their secrets out on a tattered blanket to sell at market.

Welty pointed out, “The reason why every word you write in a good novel is a lie, then, is that it is written expressly to serve the purpose; if it does not apply, it is fancy and frivolous, however specially dear to the writer’s heart. Actuality, it is true, is an even bigger risk to the novel than fancy writing is, being frequently even more confusing, irrelevant, diluted and generally far-fetched than ill-chosen words can make it.” To sum her up, I think, life is a tawdry, misshapen thing, which can often get in the way of the necessary neatness and larger pattern of a work of fiction.

There are the messy truths of our lives, but then the neat packagings of fiction; even books with the least amount of narrative resolution offer an end. They come with a pretty cover over which the author and marketing and sales teams and editor and agent agonized for months and finally formalized into a .jpeg-ready file. There are blurbs that have been finalized. There is a product with a price tag on a shelf at your nearest bookstore. There is resolution in fiction that rarely, if ever, exists in real life. There is a reliability to fictional characters, even if that reliability lies in their unreliability—a reliability that is never, ever there in real, erring, flawed, volatile human beings.

Real people are not finished, not packageable, not resolvable, and I could never replicate that. Each person lives inreality—a more inviolable, and ultimately more frightening, place than anything in fiction.

——————————————

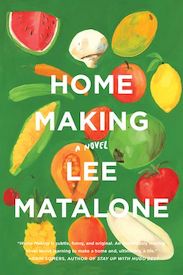

Home Making by Lee Matalone is now available from Harper Perennial. All rights reserved.

Lee Matalone

Lee Matalone writes about death and loss for The Rumpus. Her fiction has been featured in the The Offing, Denver Quarterly Review, Hobart, Joyland, Jellyfish Review, Nat. Brut, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, the Austin Review, and Cosmonauts Avenue. Her essays and reporting have appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, the National, and Flavorwire, among others. She has been a contributor to the Tin House, Bread Loaf, and Sewanee writers conferences, and has been awarded residencies at the Arctic Circle program, Pocoapoco and Art Farm. Home Making is her first novel. She lives in South Carolina where she is a lecturer at Clemson University.