On the Joys of Food-Centered Fiction

"I had never considered that food could be a tool of so much more than mere sophistication."

A classmate in an undergrad writing workshop once said to me, “Did you know that the word wine shows up in every one of your stories?” He was absolutely right, but I’d had no idea until he told me. To me, the phrase “a glass of wine” is one of the beauties of the English language, and though I didn’t drink much wine in undergrad, I realized I was mentioning it simply for my own pleasure—I wanted to place an object in my story that was beautiful and desirable, to me and to my characters. Our brains take certain pleasure at the mere sight of certain words on the page: for me, the words wine and cream set off little starbursts in my head, so much so that I will recall even an unremarkable scene involving those words for years, even decades.

This love for food-related reading goes all the way back to my childhood. One of my early favorite books was a picture book by Russell Hoban called Bread and Jam for Frances, which is the story of a picky little badger who scorns everything except the titular sandwich. Sick of trying to persuade her to eat anything else, Frances’s mother finally obliges and serves her bread and jam while the family eats a wide variety of appetizing meals and her friends unpack the most glorious little lunches involving tiny salt and pepper shakers and hard boiled eggs and cookies and clusters of grapes and so on. (Eventually Frances realizes variety is better than monotony.) I was not a picky eater, so for me the lesson of this book was that I needed to get my hands on tiny salt and pepper shakers for my school lunches.

I was equally obsessed with the food of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House series, or rather I was obsessed with the series because of the food. Recall, if you will, that while Laura and Mary are contentedly batting around pigs’ bladders and treasuring water served in little tin cups they got for Christmas, Ma and Pa spend their lives working desperately day and night not to starve. No wonder the food was so important. But it was joyful, too. Ingalls Wilder took the time to describe the way tart lemonade with sugary frosted cake at a birthday party changed the taste of both, or how Ma fried little puffy cakes in oil–vanity cakes–for Laura’s own homespun party. I assumed that my busy mother of three could figure out a 20th century hack for this recipe. She refused, for some insane reason. Forty years later, I’ve been content to leave it in my imagination.

I was mesmerized by anything about other people’s food habits and desires, what they liked and what they hated and what they ate without worry about fat or calories. Do you realize Harriet the Spy ate milk and cake every single day after school? That in Judy Blume’s novels, grandmothers were always tossing raw eggs into milkshakes to nourish their skinny grandchildren? Edmund Pevensie throwing away his soul and his family for a taste of Narnian Turkish delight sounded fairly reasonable to me. Sure, siblings are blood, but are they delicious?

As I got older it was more about what I hoped to learn. There are many pleasures to Heartburn, Nora Ephron’s lone novel and roman à clef about the end of her marriage, but one of them is a classic pasta dish I read about there and have been making ever since: fresh tomatoes, basil, olive oil, tossed with hot pasta. That’s it. It felt like a dish I could make after school as a teenager, and so I often did, chucking in chili flakes or capers or skipping the fresh herbs if I didn’t have them. I still make it, along with much of Italy, because it is a classic for a reason. But back then it was brand new to me.

By learning about wine, you can learn almost anything.

Sometimes food writing was aspirational, other times it was simply heartbreaking. In Jhumpa Lahiri’s story “Mrs. Sen’s,” a young American boy watches his babysitter, Mrs. Sen, try to get settled in the U.S., and part of his interest is in the cooking that fills their time together. But an expertise that is fascinating and rich to him and to the reader–his own mother suddenly seems rather limited and withholding in comparison–can become a source of vulnerability and foreignness out in the world, when a bus driver asks if Mrs. Sen can speak English and tells her to open a window to avoid disturbing the other passengers with the whole fish they’ve traveled to obtain.

Like any young food obsessive, I got deep into MFK Fisher for a time, which meant I became obnoxious in fresh new ways: even I suspected I should pull back on phrases like “honest bread.” So much of her writing captivated me: the cauliflower she cooked with cream and cheese, the pheasant aged almost to the point of rot, the peas picked, cooked and eaten practically in the field. But the undercurrents of sex, anger, grief, and darkness are what make her work more than mere travelogue. Husbands had a habit of appearing and disappearing without much explanation—Fisher’s biography is fascinating in its own right, though she did not choose to lay it out in detail in her own work—and more than once she used a meal to reveal the upheavals going on around the table. In one of my favorite essays, a young and newlywed Mary Frances happens upon the aftermath of a scene in which a man seems to have dined on grapes and bread while his desperate girlfriend lay naked before him. He satisfied his appetite by deriving pleasure from refusing hers, it seems; he left crumbs and grape skins on her bare belly. I had never considered that food could be a tool of so much more than mere sophistication, but true desperation, manipulation, desire, and even monstrousness.

Anyone who has encountered me in print or person has heard me talk about Laurie Colwin, and I’m heartened to see that her influence seems only to keep growing decades after her death. Colwin’s fiction and nonfiction are the antithesis of every snobby cliché; she exhibits interest, amusement and pleasure at nearly every food the world could offer (the exception was the British dish “starry gazey pie,” which involves a clutch of eels gazing out of a pastry crust toward the heavens). She is of the school that says you always tell us what the characters are eating, and so am I.

The literary food moment that has lodged in my brain most recently, but maybe the most effectively, is a passage from Gabrielle Hamilton’s Blood, Bones and Butter. It is nothing more than a paragraph of young Gabrielle sitting on her mother’s lap after dinner, but it is a powerful evocation of the physicality of childhood. Our early time with our parents is one of near-boundless physical intimacy with their looks and their sounds and their habits and their powers and frailties, even as they do nothing more than, say, crack walnuts or peel clementines. It’s one of those passages I give to students, writers, readers of all stripes. I go back to it over and over myself, collecting the moments when the words light off those familiar starbursts in my brain.

It’s a pleasure-seeking that can shape your life. I took a job in a James Beard Award-winning restaurant in my early twenties not because I wanted to open my own restaurant or become a chef. I wanted to learn on the job and with an employee discount, sure, but I also just wanted to be in a place where we talked about the things that made me feel full of delight. That job lasted only three years, and yet in my writing I keep going back to the things I learned there: the theater of a restaurant, the immense, repetitive and yet gratifying work of growing and producing food and wine.

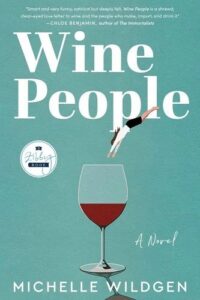

That’s why when I started researching the wine industry for my novel Wine People, I returned to an old restaurant colleague. She’d gone on to work in wine importing, and I realized as I talked to her that by learning about wine, you can learn almost anything: it can send you down paths of history, gastronomy, family relationships, chemistry, ambition, geology, geography, agriculture, travel. I love a glass of wine, but I am most entranced by all the stories that can unfurl from it. “Wine was the one thing that taught me everything else,” my friend told me. And I know exactly what she means.

__________________________________

Wine People by Michelle Wildgen is available from Zibby Books.

Michelle Wildgen

Michelle Wildgen is the author of the novels Wine People (August 2023, Zibby Books), You’re Not You, But Not For Long, and Bread and Butter, and the editor of the food writing anthology Food & Booze. A former executive editor with the award-winning literary journal Tin House, she is a freelance editor and creative writing teacher in Madison, Wisconsin.