On the Indian Revolutionaries Who Plotted to Overthrow the British Raj From America

Scott Miller Explores the Diverse Communities of Students and Laborers Who Sought Independence From Colonial Rule

Christmas morning in 1912 was simply glorious in San Francisco. Under a brilliant blue sky, a crowd of children dressed in their holiday best dragged their parents to Golden Gate Park. None other than Santa Claus himself was to preside over a yuletide festival the likes of which the city had never seen. Some twenty truckloads of toys and sweets were to be distributed. And the city had erected its first official Christmas tree, a nearly fifty-foot-tall “monster” that had been decorated the night before. Brilliantly costumed musicians led nearly twelve thousand children in songs including “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The San Francisco Examiner gushed that the park was “blooming like a garden of God.” At around 2:00 PM, San Francisco’s recently elected mayor, James “Sunny Jim” Rolph, a cowboy-boot-wearing Republican business tycoon, arrived with his own three kids to wild applause, and the celebrations began in earnest.

Across the bay from San Francisco, in the town of Berkeley, a group of fifteen to twenty students from India was holding its own celebration, gathering at a house several of them shared about a half mile from the University of California, Berkeley, campus. The high-quality universities of the Bay Area had attracted students from India for several years, offering a compelling combination of academics and, it had to be said, temperate weather. As one Indian warned prospective fellow students, American universities on the East Coast had a climate that was “colder than your ice cream.” For the group gathered on Christmas Day, a feast was held, and dinner plates were piled high with food, a luxury for students who watched every cent.

The party was buzzing with excitement over a visitor most definitely not from the North Pole—Har Dayal. Slightly built, affable, and projecting confidence through his wire-rimmed glasses, Dayal was a legend among Bay Area students from India. Many had heard his speeches or read his articles on any number of subjects and were well aware of the exalted place that he held on San Francisco’s social register. Among those he had befriended were the columnist John D. Barry, the newspaper editor Fremont Older, and the novelist Jack London. London, in fact, based a character on Dayal in his novel The Little Lady of the Big House.

Integral, too, to Dayal’s mythology was his monkish existence.

The apartment where he lived near Berkeley’s railroad tracks was furnished with a single chair, which was there only so that his friends would have a place to sit. He himself sat and slept on the bare floor without even a mat. The closets remained largely empty. His wardrobe consisted of a single threadbare brown tweed suit and shoes with holes that let the rain in. Once when friends stole his tattered overcoat to force him to buy a new one, he replaced it with a secondhand garment that looked just as shabby. What little money he had, he often gave away, sometimes forgetting to even eat. As one of his best friends, the famed literary critic and biographer Van Wyck Brooks, once noted, Dayal was completely detached from the “vanities of the world and the flesh.”

America inspired Dayal. There he discovered freedoms unknown during his life in Britain and in India.

Such deprivations were more a matter of choice than of necessity. Dayal had grown up in Delhi in a world of relative privilege as the son of a prosperous Hindu court employee who worked for the British. Education and personal advancement were prized. By the time he reached his teens, he was famed as “the most brilliant man in the whole province of the Punjab,” in the words of a Berkeley student who knew him as a child. Friends said that he possessed a photographic memory and that even at a young age he was able to recite entire books. In one oft-repeated story, Dayal was said to have played a game of chess, counted the rings of a bell, repeated verses in Arabic and Latin that others recited to him, and worked out a math equation—all at the same time.

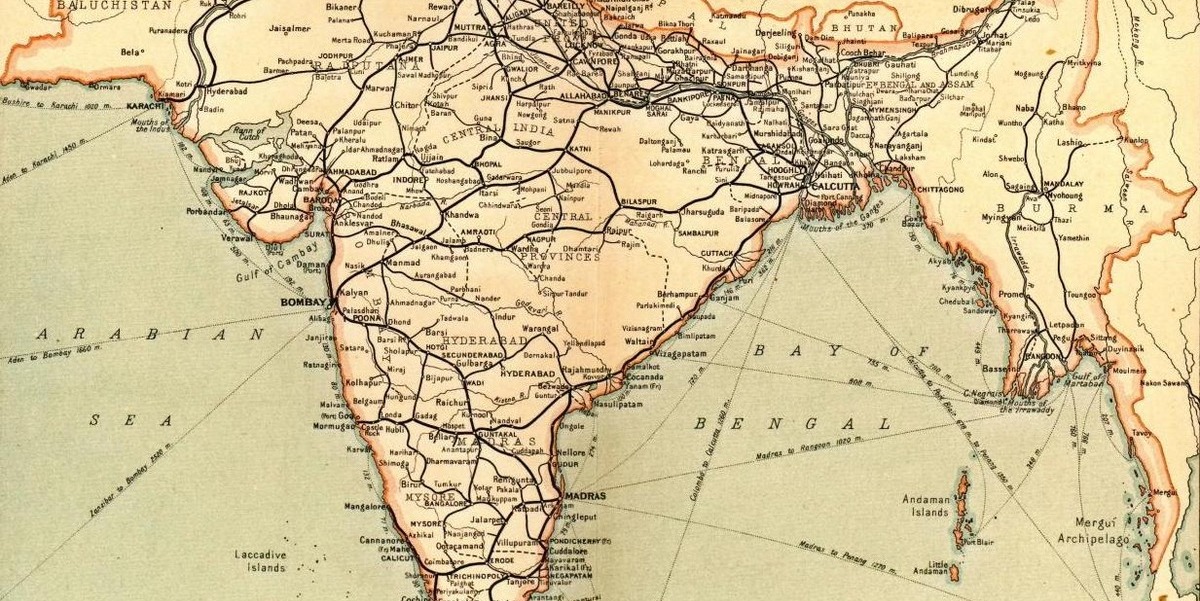

Dayal’s intellect was not limited to his exceptionally good memory. He was developing clear ideas of his own about politics. The India of his youth was still deeply scarred by a massive anti-colonial uprising known as the Indian Mutiny. In 1857, Indians serving in the army of Britain’s East India Company, who were known as sepoys, had revolted over the seemingly innocuous issue of the ammunition used in their Enfield Pattern rifles. According to rumors spread among the sepoys, the cartridges were sealed in a tallow made from cow and pig fat. To Hindu and Muslim soldiers, this detail was perceived as a humiliating and possibly even deliberate attack on their religious beliefs.

Indian soldiers turned on their British officers, and for over a year the country was consumed by mass bloodshed. The majority of the atrocities were committed by the British, who made it their policy to so terrify Indians that they would never contemplate a similar uprising again. One of the most gruesome punishments was “blowing from a gun,” in which a prisoner was tied across the muzzle of a cannon before it was fired. Such a form of execution, which sprayed body parts up to a hundred yards, made performing traditional funeral rites for Hindus and Muslims impossible. In the end, it is thought some six thousand British citizens and eight hundred thousand Indians died.

Imbued with the spirit of the uprising, Dayal by his late teens had embraced the teachings of some of India’s leading nationalists and developed a reputation of his own. Though one school administrator refused any suggestion that Dayal was disloyal, employees of the British Criminal Investigation Department wrote in a 1904 report on him that “a sense of revolt had taken deep root in his mind and had even permeated strongly a select circle of his friends.” Still, when Dayal was twenty-one and considered a “scholar of exceptional qualifications,” he received a prestigious scholarship to St. John’s College at Oxford, after which he could have looked forward to quickly advancing through the ranks of Indian bureaucrats who helped the British rule the country. It meant for a time leaving behind his wife, Sundar, the daughter of a wealthy judge, whom he had married at age seventeen, but the opportunity was too great to pass up. At Oxford, with the exception of his miserable play on the intermural soccer pitch, Dayal had impressed fellow students and professors, and his future seemed all but assured. But by his second year, while studying European history and British rule in India, Dayal soured on the idea of ever taking a job in the bureaucracy back home. He began attending gatherings in the tony Highgate area of London at India House, a breeding ground for the nationalists then living in England. And he tried his hand writing articles critical of the British, one entitled “A Sketch of a Complete Political Movement for the Emancipation of India.” This he followed with a letter to a magazine calling on Indians to devote themselves with a “religious spirit” to the cause of independence. Young men supporting India’s freedom along the lines he envisioned should abandon “the vulgar craving for wealth, social rank and physical comfort,” he wrote.

By 1907, Dayal decided that he could no longer accept funding from the enemy. To the astonishment of fellow students and professors alike, and even drawing notice from members of Parliament, he gave up his scholarship and a future in the British civil service. Such a path, he concluded, amounted to accepting golden handcuffs that killed a revolutionary spirit. “Those who feel proud of their country and nation are cured of this pride by accepting service under government, while those who would have used their gifts and abilities in rousing their countrymen have their whole time taken up in writing judgements or doing other government work,” he wrote. One of his friends described this stunning decision as “a most profound psychological change, a deep conversion, a self-conversion, the sort of experience that new prophets go through.”

Over the next several years, Dayal adopted the role of a self- styled “political missionary” and launched a campaign to convince other young Indians to follow his lead. After a brief spell in India, he left his wife and baby daughter behind with little prospect of seeing them anytime soon and wandered the world in a political and religious quest—traveling back to England, then to France, Algeria, Martinique, and ultimately to the United States. In America, he had heard from a friend, he could nurture his latest interest—Buddhism—at Harvard. Although he was greatly impressed by people he met in Cambridge, Massachusetts, his desire to campaign for India’s freedom gnawed at his gut. California, home to a growing and active community of his countrymen, felt like where he belonged, and in the spring of 1911 he headed west and quickly developed a reputation as a man of provocative ideas. Everything seemed to interest him, from the plight of women in America to Marxism to philosophy. In an article in the American magazine Open Court, he wrote: “We live in an age of unrest and transition. The old order is changing in all countries and among all nations, but the new is not yet born.” With his Oxford pedigree and obvious knowledge of Eastern religions, he within a year came to the attention of Stanford University, which offered him a lectureship.

America inspired Dayal. There he discovered freedoms unknown during his life in Britain and in India. “The great flag of the greatest democratic state in the world’s history, burns up all cowardice, servility, pessimism, and indifference, as fire consumes the dross and leaves pure gold behind,” he wrote. America was “perhaps the only country in the world from which a solitary wandering Hindu can send a message of hope and encouragement to his countrymen.”

*

The Berkeley at the Christmas party in 1912 found Dayal in a particularly animated mood. Their hero had received news from India just days before that he could not wait to celebrate. On December 23, the British viceroy in India, Lord Hardinge, had led a parade through Delhi to celebrate the British decision to move the capital there from Kolkata (which at the time was called Calcutta). Resplendent in a blue jacket with gold braid and a chest full of medals, the viceroy and his wife rode atop an equally well-adorned elephant through Delhi’s main street, the Chandni Chowk. Just as they reached the Punjab National Bank, a bomb detonated. Heard miles away, the explosion killed a servant and severely wounded the viceroy.

Shaken by the attack, British leaders in India immediately launched a hunt for the assassin. They would not discover his identity for over a year. But Dayal claimed to already know that “one of my boys did it.”

How much Dayal really knew was hard to say. As someone who was at the party that day noted, he had been away from India for years and likely didn’t have any close relationships with revolutionaries there. Nor had he engaged in much seditious activity since arriving in the United States. But Dayal’s friend Gobind Behari Lal wrote that the Christmas party marked a turning point in his life: “He knew that he would never go back to India. Now he must do everything he could from abroad.”

*

American campuses were by 1912 an increasingly popular choice for bright young scholars from India. Though the universities may have lacked snob appeal—British officials suggested that an undergraduate degree from Oxford was worth more than a PhD from Harvard—American colleges still offered a first-rate education in subjects that students from India prized: medicine, engineering, and agriculture. And, critically for cash-strapped students from South Asia, American schools embraced the idea of working odd jobs to cover tuition. As Dayal noted, “America is the land of opportunity for poor, industrious and intelligent students,” adding that “no one who can lead a rough and simple life need return from this country without a university degree.”

Yet higher education on the West Coast came with a bewildering collection of uniquely American traditions. As Gobind Behari Lal said of his university days, “The experience of the Berkeley campus was simply amazing to me, because it was completely different from the British system.” There were fraternities and marching bands and the “Big Game,” a football showdown between University of California, Berkeley, and the upstart rival, Stanford University. The month before Christmas, the two schools temporarily replaced football with the “safer” sport of rugby and fought to a rain-soaked 3-3 tie in the infamous “Mud Bowl.” Other marvels included sharing classrooms with women. Professors dealt with students as equals, even as friends. “I was so excited and enchanted,” Lal wrote.

No amount of fervor could overcome the depressing reality that Dayal had at best a few dozen followers.

Cultural land mines dotted the landscape. Did hot dogs have something to do with canines, one student wondered? Another advised prospective young Indian scholars that in “Yankeeland,” they would need to rethink how they dressed. Their fancier English clothes from home made “a man look ludicrous” on informal American campuses.

Indian students were also well aware that they belonged to a different social stratum than their fellow white classmates. In a frank and evenhanded assessment of their life on US campuses, one said that his American classmates on balance held racist views toward Indians and their religious beliefs and were not particularly interested in learning about their culture. But he wrote that “the American is always a very pleasant person to meet,” adding, “These American youths seem to be possessed of incurable optimism…He sees no lion in his path; he knows no defeat.”

In the United States, Indian students tended to live together in rented houses, where they took turns with chores and cooking, usually simple fare such as rice, vegetables, and dal. Though curry was virtually unknown on the West Coast, it was easier than expected to find necessary spices, such as cumin or turmeric, for cooks willing to look for them.

Among many of the nearly forty Indians attending UC Berkeley, Dayal had assembled a loyal following. In fact, through his position on a scholarship committee, he had had a hand in bringing some of them to the Bay Area, and many were anxious to take a stand, any stand, against the British. In early 1913, one group of Dayal’s supporters, inspired by the Christmas party, targeted an otherwise sympathetic University of California professor named Henry Morse Stephens. The academic, who edited a magazine about India and had lived there, was supportive of the nationalist movement. But he insisted that independence could never be achieved by civil unrest or bombs. Such moderate views sounded like a selling out to Dayal’s followers, and they turned up in force at one of Stephens’s speeches, “striking figurative and literal fists at the gentleman.” When some students resisted Dayal’s arguments for turning on the British, he was apparently more than willing to make his position clear. His visits to their houses were punctuated by arguments and tense moments. As one put it, “His presence caused a good deal of trouble.” And for those who needed still more persuading, there were accusations that he held up funds from the scholarships he helped administer to those who weren’t sufficiently supportive.

Of all the rebellious students that Dayal met, one stood out: a former University of Washington political science major named Taraknath Das. Slightly built and intense, Das had fled India to escape colonial authorities who had identified him as a troublemaker. After a brief spell in Japan—where he found the language impossibly difficult—he arrived in Seattle in 1906. Intelligent and industrious, Das managed to get a job in the US immigration service and was dispatched to Vancouver. There, his day job was to help Indians passing through Canada on their way to the United States, but he again began to campaign against the British, publishing a seditious newspaper in Canada called The Free Hindustan. In one article, Das wrote that Sikhs in North America were “awakening to the sense that they were nothing better than slaves and are serving the British Government to put our mother country in perpetual slavery.” At his urging, many Sikhs in Vancouver who had served in the British military threw away their service medals.

During his time in Vancouver, Das had begun what would be years of confrontation with Hopkinson, trading a series of victories and defeats. Hopkinson landed the first blow when he drove Das out of Canada by leaking a story about him to The Times of London and complaining to American immigration authorities about their employee’s moonlighting as a rabble-rouser. Hopkinson and British diplomats in Washington then managed to get Das expelled from a military school on the East Coast. His passions, though, never faded. Once, a lecture he gave at a California women’s club on Hindu philosophy devolved into an anti-British rant, promoting boos and hisses that made “havoc of the customary serenity of the club.” After he was escorted by the hostess from the stage, “many cups of tea and great slices of cake were consumed in an attempt to mend the peace which had been so dreadfully shattered.”

It hadn’t taken long for Das and Dayal to find each other. Das, who in January 1913 was working in Colfax, California, for the Pacific Gas and Electric Company, had attended the Christmas party where Dayal had celebrated the attack on the viceroy and, some would claim, joined Dayal in strong-arming students to sign on to the movement. According to one account, the pair would sometimes verbally abuse those who didn’t with taunts that they were traitors and spies. Resorting to such tactics exposed a glaring weakness in the resistance movement. It was true that some of the students were fanatically devoted to liberating their homeland. But there was no escaping one fact—their numbers were absurdly small. No amount of fervor could overcome the depressing reality that Dayal had at best a few dozen followers.

*

There was a deeper pool of potential revolutionaries equally determined to effect change in India. By 1913, Indian farmhands, factory workers, loggers, and railroad men were beginning to organize in Washington, Oregon, and California. And their leaders were eager to meet Dayal.

These immigrants were vastly different from the students inhabiting Dayal’s academic world. They were laboring men with thick calluses on their hands and work pants stained with dirt and oil. Their experiences in America were nothing like what Dayal had personally confronted, where, as he put it, “a Hindu’s nationality is a passport to social intercourse in the upper classes.” Living far from the urban centers of the West Coast, they also encountered significantly more prejudice. Though they were thousands of miles away from the Jim Crow regime of the Deep South, virulent racism was still common in the Far West. Some people had deliberately moved there seeking to avoid immigrants from southern Europe as well as Black people, who were then migrating to northern cities for work. Such bigotry was easily directed at South Asian immigrants. At theaters, barbershops, saloons, and cinemas, seats were set aside for people of color, including Indians. Even a simple trip to the grocery store meant enduring mean stares and venomous whispers. Sikhs, who constituted the largest share of Indian workers, felt particularly vulnerable.

One of the world’s youngest major religions, Sikhism was born in Punjab in the late fifteenth century and is based on the teachings of ten principal gurus, or spiritual guides. Among its core values are equality, social justice, tolerance of other religions, and devotion to God. As part of this devotion and as a symbol of their brotherhood, many Sikhs refuse to cut their hair, keeping the long strands organized with a turban. To many white Americans who knew nothing of the faith, the headgear was unusual, and it made its wearers a focal point of abuse. One newspaper headline jeeringly warned Americans of a “turban tide” of immigrants.

In 1905, some of California’s leading citizens formed a group to fight immigration from across the Pacific, which came to be called the Asiatic Exclusion League. (The original name, the Japanese and Korean Exclusion League, was changed to recognize the group’s opposition to Chinese and Indian immigrants as well.) The league’s membership included some of the great and powerful of the American West, with men such as the San Francisco mayor Patrick Henry McCarthy and the labor leader Andrew Furuseth. Eventually enrolling some one hundred thousand supporters in branches up and down the West Coast, the group was all too often willing to resort to violence to achieve its exclusionist ambitions. Many of the Indians who suffered discrimination could point with a shudder to what happened in 1907 in Bellingham, Washington, as a turning point. The rough timber town, about ninety miles north of Seattle, had once been a magnet for Indian laborers. Employers loved them. Mill owners could get away with paying Indians $2.00 a day, rather than the standard $2.22. What’s more, they were willing to take on hardships such as double shifts, which other employees would often refuse. As one mill owner said, “You find a lot of people who kick because some of us hire orientals but I can’t see any reason why we shouldn’t because they are good men and mind their own business.”

White working men predictably held a different view. A sudden influx of foreign workers willing to accept low wages threatened their livelihoods. As the Puget Sound American wrote, “The dusky Asiatics with their turbans will prove a worse menace to the working classes than the ‘Yellow Peril’ that has so long threatened the Pacific Coast.” There was no doubt that skin color, clothing, and unfamiliar religious practices contributed to the feeling that Indians could not assimilate. But India’s caste system also raised concerns. Though many of the Indians who came to the United States were of similar social strata, some Americans were aware of the sharp divisions that existed in India. In one issue of a magazine entitled The White Man, which advocated for the exclusion of Asians from the United States, a writer described the caste system as a regime in which the low-ranking man was considered an “evil thing” and a source of “pollution.” Upper-caste Indians, the article said, were prevented from almost any form of contact with lower castes. “Imagine a condition in the United States wherein a carpenter could not touch or speak to a shoemaker without endangering his immortal soul.”

Shortly after Labor Day 1907, the loggers of Bellingham decided to take matters into their own hands.

On September 4, a mob of white men and women attempted to physically drive the roughly 250 Indians who lived there out of town. Their plan, recorded by a local newspaper the next day, was to scare them “so badly that they will not crowd white labor out of the mills.” A horde estimated at around five hundred marched on the barracks where Indians lived. Perhaps fueled by the many saloons in town, they smashed down doors and threw personal possessions outside. Anyone not quick enough to escape was beaten. The chief of police, powerless against the size and rage of the mob, managed to prevent serious bloodshed when he offered the Indians refuge in the city hall. The next day, police escorted many to the railroad station, where they boarded a Great Northern train, and the townspeople began to come to terms with what had just happened. Journalists engaged in no small amount of hand-wringing. One reporter, who like many Americans didn’t differentiate between Hindu, Sikh, and Muslim faiths, condemned the riot. But he added: “The Hindu is not a good citizen. It would require centuries to assimilate him, and this country need not take the trouble. Our racial burdens are already heavy enough to bear.”

News of the Bellingham riot echoed like the shot of a starter pistol. Within days, residents in towns around Puget Sound demanded that mill owners not employ Indians and landlords not rent to them. In Anacortes, near Bellingham, mill owners were threatened when a rumor spread that they planned to hire 150 Indians. The lodgings of ten Indians who lived in a cabin in Danville, Washington, was surrounded by local men and boys, who pelted the building with stones, breaking windows and injuring some of the occupants. On Halloween night in 1907, in Boring near the Columbia River in Oregon, an armed gang of men left a bar and fired indiscriminately into a laborers’ camp where Indians were sleeping, one bullet striking the thigh of a man who had been in the United States for only three weeks. He died shortly after. The assailants would later be arrested and given lengthy prison sentences, but the Indian community remained uneasy, and for good reason. When some traveled farther afield seeking work in Alaska, locals prevented them from disembarking from their steamers. In January 1908, townspeople in Live Oak, California, formed a vigilante group and drove Indian laborers from town, stealing money from them in the process.

The root of their troubles, they jointly understood, was not how they were treated in the United States. Rather, it was British rule of their homeland.

Similar acts of erratic violence continued for years as resentment simmered, until it finally erupted once again in March 1910. As in Bellingham three years before, many of the citizens of St. Johns, a newly booming town outside Portland, did not take kindly to the hundred or so immigrants who worked in the two main mills. On March 21, apparently triggered when a mill foreman went to Condon’s Saloon to demand that Indians not be served, an altercation spilled out into the street. A mob formed that quickly swelled to nearly three hundred people, including the mayor, a police chief, two police officers, a business leader’s son, and even volunteer firemen. They marched on the bunkhouses and mill shacks where most of the Indians were living. According to a local paper, “Every Hindu that was encountered was peremptorily ordered to stop work and get out of town.” Accounts varied, but some reports claimed that the mob smashed windows, ripped doors from their hinges, pulled Indians from their beds, and scattered the men’s clothes. In the investigation that followed, the townspeople refused to provide details about what had happened or who was involved. Outraged, Taraknath Das, the University of Washington student, wrote an article for the Morning Oregonian arguing that the attacks were based on racial prejudice and warning that America’s place as the “land of liberty” was jeopardized.

Several of the ringleaders were later found guilty of only minor offenses and managed to avoid jail time.

The mostly Sikh migrant workers remained in town but did not feel safe. One laborer named Sohan Singh Bhakna was deeply disturbed, later calling the St. Johns riot “a wakeup call and a game changer for Indians working in Oregon and Washington State.” In fact, the rampage would have significant repercussions for Indians throughout the country and beyond.

*

Bhakna had come to the United States in 1909 to set his life straight. As a young man in Punjab, he had fallen in with a rough group of friends, drinking, squandering his family’s savings, and eventually piling up significant debts. As he later admitted, “I wasted ten precious years of my life.” But at around age twenty-five, inspired by religious leaders, he adopted an entirely new worldview based on tolerance of any faith—Hindu, Sikh, Muslim, or Christian—and developed a revulsion to drinking. Determined to repay his debts, he was intrigued to hear from friends that considerable sums could be made in America, and he left for Seattle. Like so many other immigrants, he gravitated toward concentrations of his countrymen, finding work at the Monarch mill near Portland. His job there was agonizing for a man with little experience at physical labor. Among his duties was pushing a heavy wheelbarrow to a rooftop, a task so strenuous that sometimes he could work only half a day.

Even more painful for Bhakna was the discovery that in America he faced discrimination and rough treatment similar to what the British meted out back home. Though they worked hard, Indians were paid less and enjoyed a lower standard of living than their American counterparts. Racial prejudice was widespread. In one awkward incident that stung Bhakna’s pride, he attempted to entertain an Indian professor for lunch in a Portland restaurant.

When he asked for a table, they were refused service and had to settle for a meal in a Japanese hotel. Bhakna, who previously had expressed few political views, soon began attending meetings of the radical labor organization the Industrial Workers of the World, where he “spoke regularly about the exploitation of migrant workers and the formation of race- and class-based hierarchies along the Pacific Coast.”

By early 1912, Bhakna was ready to play a leading role in the fight. Most Sunday evenings during that year, he and Kanshi Ram, a successful contractor in the timber industry, ran meetings at a rented home in Portland to discuss the racism and violence so regularly inflicted on their community along the Columbia River. Calling themselves the Pacific Coast Hindi Association, the group of about seventy working men discussed politics and exchanged newspapers from India.

The first step toward improving their situation, they realized, was to adjust their own behavior. Where once working-class Indians might have drunk to excess, they now avoided bars. They would stop fighting over the best jobs and would help coworkers who were unjustly treated, even giving free food to those without work. They made grand plans to publicize their movement, including printing a newspaper that they hoped would draw in new supporters. The meetings were energizing, but even the leaders admitted their enthusiasm lacked focus and power. The membership didn’t grow. Money was short. The paper they hoped to launch never got off the ground. Then stories about the charismatic young firebrand in California, Har Dayal, began to reach them. Could he deliver the spark they were looking for? At the end of the year, they invited Dayal to Oregon. It would take a few months to arrange a visit, but that spring, word reached Portland that Dayal was coming.

Bhakna, Ram, and the others could hardly contain their excitement when, one evening in May 1913, Dayal finally arrived.

Telephone calls summoned friends from the surrounding area. Messages were passed. This was an event not to be missed. At a meeting at Kanshi Ram’s home off the back of a machine shop in St. Johns, the men gathered around the intellectual from California and listened spellbound as he laid out his vision. Though from a privileged background and unaccustomed to working with his hands, Dayal had a talent for establishing personal connections with people from all walks of life. He had big ideas, could write, and was fluent in English, a skill that many members of the Pacific Coast Hindi Association lacked. There were some disagreements, such as the role students might play in achieving the group’s ambitions, but Dayal and the working men hosting him were in absolute agreement about the biggest issue on their agenda. The root of their troubles, they jointly understood, was not how they were treated in the United States. Rather, it was British rule of their homeland.

For Bhakna, the decision to target the Raj marked something of a transformation. Like many in the Punjab, he had come to accept a certain inevitability about colonialism, and his opposition to it had been modest. But he could not ignore evidence of broader repercussions. Whether it be in the United States, Canada, Australia, or other parts of the world, Indians felt harshly judged for allowing themselves to be oppressed and conquered back home. American workers, Bhakna later recalled, treated them with even less respect than they did Chinese or Japanese immigrants. “Only Indian workers were slaves and orphan-like and that was the reason for their humiliation and insults,” he said. Even children made fun of them. “Many times kids will follow us in streets, shouting ‘Hindoo Slaves.’ We were made to feel too ashamed to look back.” They felt they would never be seen as equals until they were free.

Many blamed the British for directly provoking the rough treatment. In one pamphlet, Indian seditionists later wrote that the British were turning people in California and other places against them. “They bribe European laborers, set them against the Indians and publish articles containing various false charges against the latter, otherwise neither the people of Canada nor of America have any ill-feelings against Indians. There is room for all the people of the world in one part of America while there is room for a hundred million in Canada. The English are at the bottom of this mischief.”

Glaring shortcomings aside, the United States had long served as a beacon. As Bhakna noted, here one could run for political office, the police treated people more fairly than in India, and individuals could even own guns. One aspiring student recalled an inspirational encounter with an American immigration inspector when he first arrived. When asked why he had come to the United States, common sense dictated that he provide a bland, inoffensive answer. Instead, he blurted out that he had come to the “land of (George) Washington” to become a revolutionary and learn how to throw off British oppression. Quickly regretting the outburst, he thought for sure that he “was lost.” But the border agent merely patted him on the back, saying, “Go, wish you success.”

The United States offered the prospect of material success as well. Many looked to the example of Jawala Singh. He and a business partner named Wasakha Singh had secured enough money to lease a five-hundred-acre farm near Stockton, which they turned into such a thriving business that he was known locally as the Potato King. By 1912, the pair had grown wealthy enough to build the first Sikh temple, or gurdwara, in the United States.

Over long hours of discussion, starting with their first meeting in Portland and in the weeks that followed, Bhakna, Ram, and Dayal sketched the broad outlines for a new and powerful group. Bhakna, representing the working Sikhs who were the numerical and financial backbone of the movement, would soon be named president. Dayal would be selected to serve as secretary and editor of a newspaper. A “secret commission” was established to oversee clandestine activities. To protect themselves from British spies, strict measures were taken to ensure safety. Members would intentionally be kept in the dark about what others were doing. Any new recruits would have to be recommended by two people in the organization. Divulging secrets or misappropriation of funds could be punished with death. Ciphers were used for important correspondence, and only the secretary or editor could open mail. Those most devoted to the cause committed to vows of celibacy, at least until they reached the age of thirty. And to address differences in their backgrounds, they agreed that the organization must be largely secular and democratic.

But most important, they decided to “gird their loins to liberate India and work on revolutionary lines.” Their plans were ambitious. They intended to one day organize a democratic government, a United States of India.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Let My Country Awake: Indian Revolutionaries in America and the Fight to Overthrow the British Raj by Scott Miller. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2025 by Scott Miller. All rights reserved.

Scott Miller

Scott Miller is the author of That Heaven of Freedom; The President and the Assassin: McKinley, Terror, and Empire at the Dawn of the American Century; and Agent 110: The American Spymaster and the German Resistance. A former foreign correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, he reported from more than twenty-five countries in Asia and Europe for two decades. He has been a contributor to CNBC and Britain’s Sky News and appeared on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. He lives in Seattle with his wife, Karen, and a Labrador retriever, Lucy.