On the Impromptu Walgreens Concert That Got Evan Dando to Sober Up

“I’ve been lost and found more times than I can count,

but it was time to make a change.”

I dropped my wallet in the hedges of Walgreens. I’d come to Falmouth to go to the dentist. It was February 27, 2021. I’d moved to Martha’s Vineyard in 2013. Those in the know don’t go to the dentists on the island. After twenty years in New York City, the novelty of being a country mouse in the big city had worn off. For me, walking on the beach in the moonlight for a few minutes was more fulfilling than two years of New York City nightlife. Dorothy Gale and Ian MacKaye were right: there’s no place like home. So where am I?

Martha’s Vineyard has soul. There’s something in the air out there. It’s a singular place. Back in the seventies it was bursting with intellectuals. It was like a piece of Cambridge that had been chucked out to sea and floated away. Not to mention the sheer volume of children’s book authors who lived and wrote there: Judy Blume, Roald Dahl, Jules Feiffer, Maurice Sendak, and Shel Silverstein.

It’s a little bigger than Manhattan, but doesn’t have a single stoplight, just a couple of flashers. During the summer the population swells from 20,000 people to 150,000. Every summer the number gets higher. The part-time residents used to keep a beater to drive around. An old Volkswagen or Jeep made it easy to observe the forty-five-mile-per-hour speed limit. They’d walk onto the ferry, take a cab to their faithful carriage, and they were set for the season. Now they bring their $250,000 cars over on the ferry.

There’s no bridge to the Vineyard. You have to fly Cape Air or JetBlue or make your way to Woods Hole and initiate a relationship with the tough-loving Steamship Authority. I crashed at my friend and fellow musician Willy Mason’s West Tisbury house for a while, and when I had to leave, he helped me find an old trailer at 237 State Road. Shrouded by yew trees, the trailer had low ceilings and particleboard walls that were decorated with the previous tenant’s art. It had a heady, fulsome odor of black mold and wet dog. I was running out of options and hoped that good will, bad faith, hard drugs, scratch tickets, and the evil eye would sustain me.

When I watched the video, I didn’t see me. I didn’t see Evan Dando the musician. I saw Evan Dando the heroin addict.

As the years melted away, I knew I needed to do something different. I had come to the island to quit heroin, but I fell into my old habits. Martha’s Vineyard is a tough place to be a junkie. Everybody knows you there. It was impractical and embarrassing. I swallowed my pride and became a miserable pariah. Most of my real friends retreated, hoping things would change. The rest got a kick out of watching me unravel. I was in horrible shape, losing teeth, and living off cheeseburgers—which I could barely chew—Marlboro Reds, purple Powerade (two for the price of one at Cumberland Farms), and a $200 daily drug budget.

I like the Vineyard during the off-season. Being a double Viking with Swedish and Norman blood on each side of my family, the cold never bothered me. The winters keep the bad people away. That’s what Prince used to say about Minneapolis. That pandemic winter I went a little overboard. I sat around injecting dope, coke, and speed and smoking weed all day. I actually watched every episode of Gilmore Girls and I didn’t even like it. Ditto Gossip Girl, but that one was more enjoyable.

I lose stuff all the time: phones, guitars, pencil sharpeners, gin and tonics, girlfriends, jewelry, bagels, tuners…You get the idea. I had all kinds of methods for keeping my wallet and me together, but when I arrived at the ferry parking lot on Palmer Avenue, it was missing. I’d had it when I checked out of the Inn on the Square that morning, so it disappeared somewhere along Main Street. I started freaking out because the wallet had my driver’s license and a couple of debit cards, but I was really bumming when I remembered there was a photo of Keith Richards with Mick Jones of the Clash hanging by the pool in Ocho Rios that had been given to me by Keith’s son, Marlon. I posted a message on Twitter asking people to keep an eye out for it. I’d recovered a wallet in Toronto that way and also got back a stolen 1967 country and western Gibson acoustic guitar, so I was feeling pretty good about the whole thing.

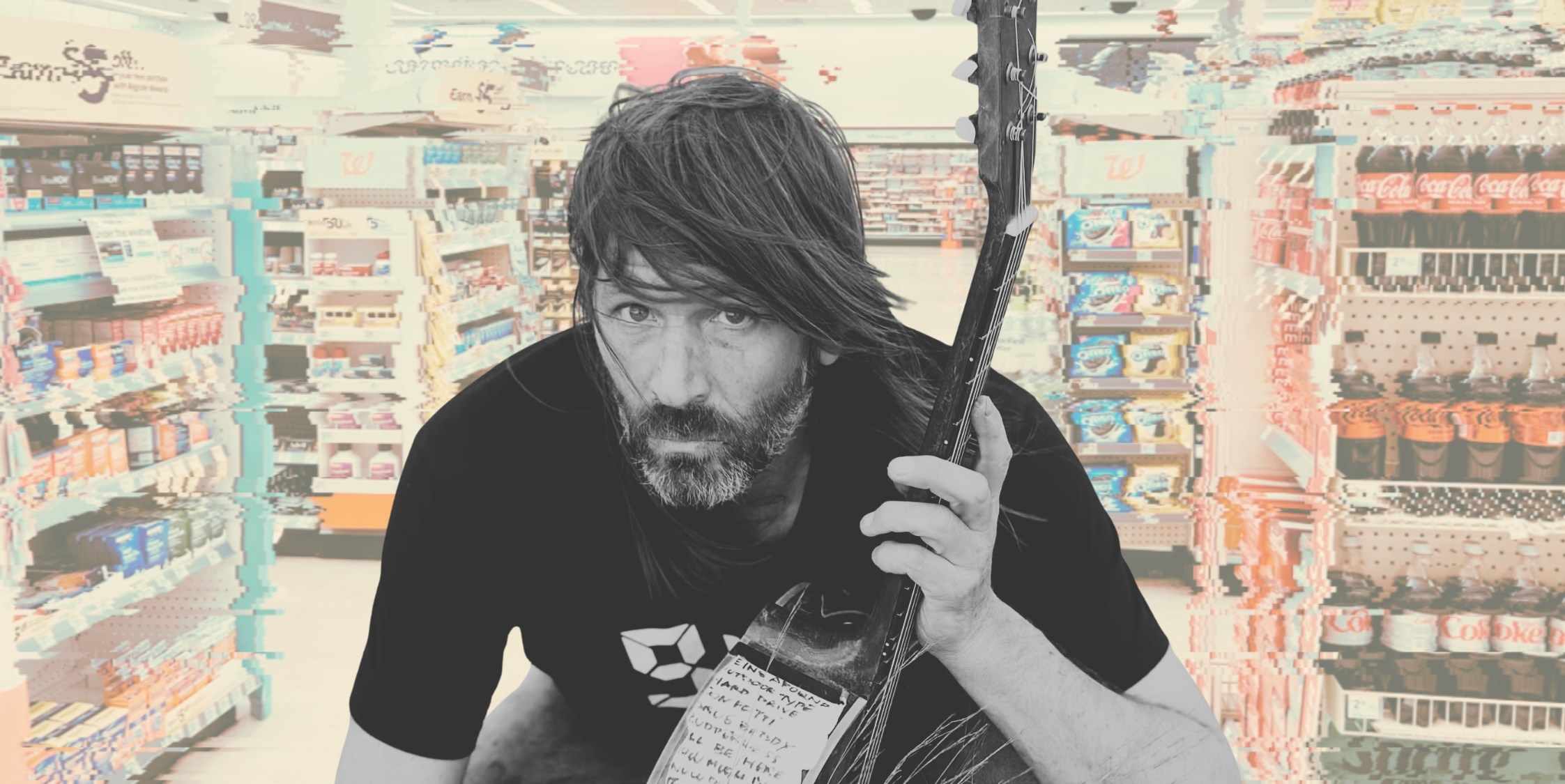

In a matter of minutes, a guy named Mike Ghelfi answered my SOS. He worked at the Walgreens on Main Street. He wrote that someone had found my wallet and turned it in at the store. I went over to Walgreens and, sure enough, it was there, and nothing was missing. I was so grateful I played a few songs for Mike and the staff and endured the gruesome chore of autographing Lemonhead candy boxes with a smile on my face.

I hadn’t planned on playing a set next to a rack of Utz potato chips at a Cape Cod Walgreens, but I was happy to do it. It was a way to say thank you. Mike recorded the performance and posted it on Twitter. By the time I got back to my trailer on the island, the video had been picked up by a few music websites. Most of the comments were positive. There were a few negative ones about me not wearing a mask, and the usual jokers who expressed their surprise that I was still alive.

The comments didn’t bother me. What bothered me was how I looked, how I sounded. When I watched the video, I didn’t see me. I didn’t see Evan Dando the musician. I saw Evan Dando the heroin addict. I was trying very hard not to be that person. I didn’t like that person.

That winter I decided I was done with heroin for good. That meant it was time to go. If I was going to finish writing my stories and composing my songs, I had to get off the island. I’ve been lost and found more times than I can count, but it was time to make a change.

*

The first Lemonheads show, if you could call it that, was on Friday, July 18, 1986, in a basement in Central Square, Cambridge. The house on Green Street belonged to the guys in a punk-metal crossover band called Meltdown. The Meltdown House had the distinction of sitting squat in the middle of the worst-kept block in Cambridge, but it had the advantage of being indestructible. When the single-room occupancy next door was gutted in a five-alarm fire, the Meltdown House wasn’t even touched. The concept of those parties was to cram as many people as possible into a very small basement, encourage everyone to get totally wasted, and then unleash the sounds of Meltdown at pain level. The band took its name from the Chernobyl disaster, which had happened a few months before. Our friend Corey “Loog” Brennan got us the gig. Corey was a disc jockey on WHRB, the student-run radio station at Harvard University and the lead guitarist of Meltdown.

Just had a special guest appearance at Walgreens by artist @Evan_Dando (lead singer of the group the Lemonheads). Thank you Evan, you sounded great as always! pic.twitter.com/GB6XOBPfnS

— Mike Ghelfi (@GhelfiPC93) March 1, 2021

Article continues after advertisement

We played the three original songs from the EP plus a bunch of covers. We did “I Wanna Be Your Boyfriend” by the Ramones, “I Think of Her” by the Forgotten Rebels from Canada, and “Ice” by the Screaming Tribesmen from Australia. We’d been exposed to all kinds of punk rock on a show that aired on WHRB called Record Hospital. Patrick Amory was one of the DJs on the show and he helped organize an event in the spring of 1986 called the Punk Rock Orgy—168 consecutive hours of punk rock from every corner of the globe. We taped as much of the show as we could. We even skipped school to make sure we recorded it all. If we missed the show we’d trade tapes with our friends. We were obsessed with the Punk Rock Orgy.

Curtis Casella, another DJ at the station, wasn’t a Harvard student, but he introduced WHRB’s listeners to proto-punk bands beyond the Saints and Radio Birdman. He hipped us to the New Zealand comp AK79, which featured a bunch of bands from the Auckland punk scene in the seventies, including the Scavengers, Toy Love, Spelling Mistakes, and Proud Scum.

We got our punk rock education from Harvard by way of WHRB. We became friends with many of the disc jockeys, some of whom became important as the band expanded its following outside the Boston area.

Patrick Amory had enrolled at Harvard and worked at WHRB beginning in fall 1983, my junior year at Commonwealth. He continued to serve as our punk guru and unofficial adviser, along with fellow Commonwealth student George Bolucas. WHRB and other prominent local college stations are among the reasons why Boston and Cambridge went on to have such a big impact in the independent music scene in the late eighties and early nineties. With the rise of college radio as an industry force at the national level, it was some kind of epochal bonanza we were living through.

A few days after our mini-triumph, Jesse wrote a “press release” in an attempt to get some club dates:

The Lemonheads are a rocking melodic punk trio from Boston and environs. All recently out of high school, the Lemonheads play a ’77-style thunk that’s well-documented on Laughing All the Way to the Cleaners, their forthcoming 7″ EP on Patrick Amory’s Angry Arms label. Their radio tape “Glad I Don’t Know” has received massive play on WHRB and WMBR [the MIT station]. The Lemonheads have played Cambridge parties to enthusiastic crowds of over a hundred people.

People were stoked about our show at the Meltdown House, which led to the Lemonheads’ first club gig the following month at the Rat in Kenmore Square in Boston, in August 1986. We gave a copy of Laughing All the Way to the Cleaners to our friends at the Harvard station and they kept playing our record and hyping the show. This had a huge impact because when the Lemonheads hit the stage at the Rat, we had three hundred people in the audience. That’s crazy for a Tuesday night in August.

Holly was finishing up at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, and couldn’t make it, but my mom went. She wouldn’t have missed it for the world. The night of the show she had a big dinner party at the apartment and brought a bunch of her friends to the Rat, including Ben Zander, the conductor of the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra—and he liked it. You won’t find a bigger fan of the Lemonheads than my mom.

About twenty of our former classmates from Commonwealth came out to support us. So did a bunch of locals from the music scene, like Chris Brokaw of Come; Billy Ruane, the promoter at T.T. the Bear’s Place in Cambridge; Corey from Meltdown; and all the people from WHRB. We’d been to lots of shows at the Rat with much smaller crowds.

That winter I decided I was done with heroin for good. That meant it was time to go. If I was going to finish writing my stories and composing my songs, I had to get off the island.

I loved being onstage and thought we played well. I wasn’t nervous and didn’t find it difficult at all. It was a little bit like the first time I had sex: effortlessly fun. When I was fifteen, I lost my virginity to a classmate. We were dancing at a party and she came up to me and started banging her butt against mine. Then she asked if I wanted to fuck her. We found an empty bedroom, and one thing led to another.

We gave traveling punk bands that played in Boston and Cambridge a tape of our music, and the next time they came to town they invited us to play a show together. Not only did we get a lot of gigs that way, but we met all the people who booked shows at the clubs in town.

Everyone was supportive of each other. Nobody had a “career.” We worked hard, put up flyers, and went to a ton of shows. Some might say there was a lot of cronyism involved, and there definitely was, but the DJs at WHRB put a lot of work into promoting us on the show Record Hospital. We were loyal listeners, and they appreciated our support.

The Lemonheads had its ups and downs. Our second club gig was much more subdued. We played a Nu Muzik night at T.T. the Bear’s Place with a band that was also playing its second show ever: the Pixies. I’ll never forget that show. The first couple of times we saw them play, there would be thirty people in the audience. We must have seen them ten times before they got famous. They seemed fully formed and ready to take the world by storm even though they were using little tiny guitar amps set on chairs.

Word was starting to get out about the Lemonheads. Ben had a van, and we spray-painted The Lemonheads on the side so that people would get to know the name. We circulated tapes of our EP all summer, and Laughing All the Way to the Cleaners finally came out in August. We put the sleeves together at Jesse’s parents’ house. We were the proud owners of one thousand Lemonheads records. Now what?

We met and became friends with the guys in Gang Green, a hard-partying punk band that started in the suburb of Braintree and moved to Boston. Their first single, “Sold Out,” was the first release by Taang!—a local independent punk label started by WHRB DJ Curtis Casella. Curtis introduced us to Gang Green. The legend goes, Curtis signed them after listening to their tape in his car in the parking lot of the Channel while waiting for Bad Brains to show up. If Bad Brains had been on time, Curtis might not have started his label, but Bad Brains were never on time.

We met Chris Doherty of Gang Green at a show with Jerry’s Kids and Society System Decontrol (SSD) at the Paradise in 1984. It was billed as “the Last Hardcore Show.” Springa, the singer of SSD, announced from the stage, “We started hardcore here and we’re ending it here tonight!” Before the show I met Springa at McDonald’s. Me and my friend John were snorting Excedrin off the table in the middle of the restaurant, trying to be cool. Springa just shook his head. “Kids, get some real drugs.”

We got to know SSD and all the bands. The Taang! bands used to hang out at Curtis’s house, dubbed “the Taang! House,” in Auburndale, west of Boston. Curtis suggested we put our EP in with the press kit for the new Gang Green album, Another Wasted Night. That was the turning point of us becoming something.

One of the places that sold our record was Newbury Comics, a legendary independent record and comic book store on Newbury Street, with a second location in Harvard Square. The Newbury Comics people were huge supporters of Boston punk and indie music. They had this place in the store where they displayed the top twenty singles. Every week they’d rearrange the singles display to reflect the popularity rankings. I used to go to the store just to look at it, and it was a thrill to see our record move up the charts. I don’t remember how high we got—but we went through all one thousand copies in a matter of months.

We knew that certain punk bands like Black Flag put out their own records. We stood out from the pack—not because we were any good, but because we had a record. We also had our fair share of bad shows. The thing about Ben and I switching from drums to guitar all night messed with my muscle memory. It was a real hassle. Sharing a vintage Gibson SG meant constant tuning problems.

The best thing that happened to our little record was it getting reviewed by Spin magazine. The Spin review was a direct result of being included in Taang!’s official mailing to a variety of punk-friendly publications. Spin plucked it out of the pile and covered it, and not only did they review it, they liked it. Spin wasn’t the only publication to show us some love. We got a lot of coverage from that Taang! mailing, including a review in the punk zine Maximum Rocknroll.

All this love from the press led to some incredible gigs. The Angry Samoans were huge for us. When they came to town, we brought them a cake. Our friend Andrew Hendrickson frosted a cake that expertly reproduced the cover of the Samoans’ Inside My Brain EP. We brought it to their hotel and gave them a tape of Laughing All the Way to the Cleaners. The following year they invited us to open three shows for them on the East Coast, including a gig at the legendary Anthrax club in Norwalk, Connecticut. That was our first big out-of-town show.

All in all it was a successful summer. We’d made a record, heard our songs on the radio, and played with bands we loved. Not a bad start!

__________________________________

Excepted from Rumors of My Demise: A Memoir by Evan Dando. Copyright © 2025 by Evan Dando. Reprinted by permission of Gallery Books, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.

Evan Dando

Evan Dando is a singer, songwriter, and the front man for the alt rock band The Lemonheads since 1986. He currently resides in South America, when he’s not on tour.