On the Impossible Encounter That Allowed Me to Write My Novel

June Gervais Tells a Story of Happenstance at Starbucks

“The impossible still happens to us, often during the work, sometimes when we are so tired that inadvertently we let down all the barriers we have built up.”

–Madeleine L’Engle, Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art

*

My impossible thing happened at a coffee shop.

To be clear—and this will matter to the story—it was not some artsy café named, like, Inkpot + Burntbean, downstairs from a tattoo studio specializing in hand-poked sigils. It was just the corporate green mermaid place, in the unfunky Long Island town where I live.

I was there to write. In the past year I’d birthed a child, left my job, abandoned volunteering, and taken on a heap of grad school debt in a now-or-never bid to finish my novel. Was this timing ideal—recommitting to an artistic obsession while breastfeeding around the clock? No; but I’d come to realize the ideal time might never arrive.

And no matter how many times I’d tried to swear off this novel, discouraged by another not-quite-right draft, it kept coming back to me. It was about a young queer woman, fighting to become a tattoo artist in the mostly-male tattoo industry of the 80s. Like me, she felt like a lonely oddball—a strange glow-in-the-dark fish from some faraway ocean. Like me, she worried about money and her usefulness in the world, and craved time to make something beautiful. As soon as she convinces her older brother to apprentice her, however, she gets mixed up with a charlatan clairvoyant, falls in love with his beautiful assistant, stumbles into a dozen kinds of trouble—

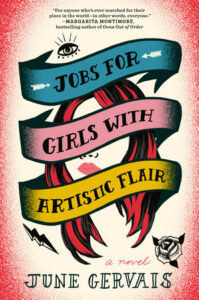

As we say on Long Island, this freakin’ book. I didn’t know it would become Jobs for Girls with Artistic Flair. I didn’t know if it would become anything. What did this novel want from me?

*

I took this question with me to the coffee shop that day. Also with me was a beat-up copy of The Great Gatsby, which I was writing a paper about. When I am stuck, certain novels hold unsticking power for me; Gatsby is one, and I was re-reading it the way you watch a magic trick. How did F. Scott Fitzgerald do it—break my heart so pleasurably, in so brief a space? If I could figure it out, would I see what my novel needed?

I needed to know gritty ’80s tattoo shops the way Fitzgerald knew swanky ’20s parties. A vivid setting isn’t everything, but for some novels it’s essential, and I had one of those on my hands.

He seduced me as always: Girls with French bobs, finger bowls of champagne. Every Friday five crates of oranges and lemons arrived from a fruiterer in New York—every Monday these same oranges and lemons left his back door in a pyramid of pulpless halves… Fitzgerald knew that place. He could throw me into Gatsby’s pool because he’d already gone swimming in it.

And I don’t know why it clicked at that specific moment, but I saw it clearly: I needed to know gritty 1980s tattoo shops the way Fitzgerald knew swanky 20s parties. A vivid setting isn’t everything, but for some novels it’s essential, and I had one of those on my hands. I pulled out my notebook and began to write this down.

This thrill of discovery was short-lived. These days, I was barely getting showers or proper meals. What was I going to do, call around to every local tattoo artist? “Hello, do you mind if I sit for long hours at your shop, skulking like a creeper? Also, can I bring my squalling baby?” Even if someone said “Oh, certainly!” it still wouldn’t solve my problem. When tattooing began to enter the mainstream in the 90s, and fully arrived circa Y2K, tattoo culture dramatically changed. Technology, health regulations, artistic styles—very little of the old world remained.

So now I knew one of the things my novel needed, but had no way to fulfill it. And meanwhile I still had a paper to write. Blah. I put all this aside and went back to Gatsby.

Here’s the impossible part.

About an hour later, I heard a voice say, “Did Eric Ziobrowski do that?”

I looked up to see a long-bearded man, tattooed from his neck to his boots, pointing at my arm. Again, we were not at some artists’ enclave (or biker bar) where all the illustrated people gather. In my many afternoons working at the corporate mermaid place, I had never seen this man.

He was pointing at the tattoo on my upper arm, an olive branch. And he’d correctly identified the artist—a man who works several towns away, one of hundreds of tattoo artists on Long Island.

“How did you know that?” I said.

“I know Eric,” the man said. “I own another shop, Top Hat Tattoo. I’m Marc.” I’d seen it. It was a five-minute drive from here.

“But how did you know it was his work?”

Marc shrugged. “I saw it in his portfolio, I think?”

“This is crazy,” I said, “but—”

I explained everything. Writer with novel-in-progress, seeking tattoo shop to stalk, but tired and lactating, etc.; subtext being holy hell, you spontaneously appeared, can I please be your friend! I tried to do this succinctly and without too much of a wide-eyed weirdo vibe.

“I have a baby too,” he said. “Sure, you can come by anytime.”

Discipline gives my writing bones; some mysterious spirit gives it breath; but the energy of other human beings jolts it alive.

We said our goodbyes and I sat there in wonder. A few minutes later, he returned and handed me his business card. “You should talk to this guy working for me, Marvin Moskowitz. He’s been tattooing since the ‘70s.”

The following week, I started making coffee runs for Marc and Marvin, and then shadowing them. Marvin, it turned out, was not just a veteran artist; he was a third-generation tattooer whose father and uncle were known as the Bowery Boys, famous Jewish tattooers who worked on New York City’s Lower East Side. When the city outlawed tattooing in 1961, they opened the first shop on Long Island.

As I began to conjure the atmosphere of my fictional tattoo shop—acetate stencils, a splash of tequila to wipe a countertop—at least half those details came from the memories of Marvin Moskowitz. This abundant gift had been hanging out a few miles away from me all this time.

*

I’ve hung onto this story like a talisman. I take it out and look at it when discouragement comes around muttering, hopeless, impossible.

I will never claim I “manifested” Marc or his coffee craving that day. I can’t even take credit for noticing him; he struck up the conversation. But in the years since then, whenever I feel a vague cloud of writerly discontent coming on, I take out my journal and write “I’m worried that…” And when the problem becomes clear: “What I need is…” Those necessary resources rarely appear as quickly as Marc did. Sometimes, in fact, it takes years of research and dead ends. But at least I know what I’m looking for.

In Madeleine L’Engle’s book Walking on Water (another classic that gets me unstuck), she recounts her own synchronicity stories. “The impossible still happens to us,” she says, “often during the work, sometimes when we are so tired that inadvertently we let down all the barriers we have built up.”

I don’t know what her barriers were, but I know mine, and the biggest can be summed up in a single sentence: I am in this alone. I must write this book on sheer self-discipline. I am a strange fish bumbling my way around an unfriendly pond, and all I can do is find myself a quiet fishbowl with a coffee maker, because I am in this alone.

At those moments when I’m exhausted, though (which is often, as a working mama), it becomes clear that I cannot do this alone. Discipline gives my writing bones; some mysterious spirit gives it breath; but the energy of other human beings jolts it alive. On the sweet day I wrote the Acknowledgements page for Jobs for Girls with Artistic Flair, I remembered how many people had made this impossible thing possible.

Sometimes I’ve found them in a very intentional way: asking to join a writer’s group, or nosing around for interviewees. But I’ve met some of the most important people in the most happenstance way, through the simple act of doing my work in a public place. The place doesn’t have to be some rarefied niche. The first step is just being around other humans. And if your book is currently causing you to lament, Impossible, impossible, I hope your future Acknowledgements page grows by one line today. Artisan mug or humdrum tumbler, I hope your coffee cup runneth over.

_________________________________

Jobs for Girls with Artistic Flair by June Gervais is available from Pamela Dorman Books

June Gervais

June Gervais grew up on the south shore of Long Island and earned her MFA in Writing and Literature at Bennington College. Her many jobs have included shelving library books and taking classified ads, grassroots activism and graphic design, art direction and teaching. Jobs for Girls with Artistic Flair is her debut novel.