On the Impossibility of Seeing Yourself

Kathryn Harrison on Aging, Asymmetry, and Looking in the Mirror

Nature gives you the face you have at twenty, life shapes the face you have

at thirty, but at fifty you get the face you deserve.

–Coco Chanel

I’m 20 when my father looks at me and says, “You know, you’ve never seen your real self. I have, but all you’ve seen is your reflection in the mirror. An image that looks very much like you but isn’t the same as you. Not really, not exactly.”

“Why wouldn’t it be exactly the same?” I ask, irritated because he’s always doing this: telling me why I belong to him and not to myself.

He explains that light is lost inside a mirror; a reflected image lacks the luminous property of the object itself. As an experienced photographer, he conveys authority about such things. “Try it,” he says, and he pulls me next to him before a mirror. “Look at me,” he says. “Look at the real me here beside you, and then look at my reflection. They aren’t the same. You’ll see they aren’t the same.”

I don’t want my father to be right. I don’t want him to own what he says he does, the way I really look, leaving me with an approximation of myself, inexact and indistinct, no better than a second-generation photocopy. But when I compare the actual man to his image, I see he’s right, they aren’t the same. The mirror father is dimmer, duller, not quite alive.

So it’s true, what he says: I have never and will never see the real me.

* * * *

The divine ratio of phi—1:1.618—determines what nature gives us. Phi unwinds the chambers of a nautilus and the spiral of a galaxy, arranges seeds in the head of a sunflower. Phi is the principle on which Leonardo da Vinci based his illustration of a perfectly proportioned human being, arms and legs spread wide, the top of his head, the tips of his fingers, and the soles of his feet all points on a single circle. 1:1.618 is the length of the hand compared to that of the forearm, the width of the face to its length, the width of an eye to that of the mouth, of the eye’s iris to the eye itself. Phi is the mathematical constant, sometimes called the “golden mean,” exemplified in Renaissance portraits and in the portfolios of Ford models.

Symmetry. Harmony. Balance. These are beauty’s terms, her demands. Exacting, like Coco Chanel. I don’t fulfill them. I know this before I do the math, dividing the length of my face by its breadth, comparing the width of my mouth to that of my eye. It’s too long, my face, either that or too narrow. My ears are where they ought to be, but they’re too small. And while no one’s features are absolutely symmetrical, I think mine may be a little more off-kilter than most. Or perhaps it’s this I notice first when looking in a mirror: a lack of symmetry.

I cover one side of my face to analyze the other. The woman on the left is approachable, engaged, pensive, but not so preoccupied that a stranger would hesitate to ask directions, say, or inquire if she’s using the empty chair at her table. The right-hand woman is another story, an altogether darker character. Not sinister, but hidden deep within herself. Aloof. She must be the one I hear described as icy.

“‘The ice queen’—that’s what we called you, when you came in for your first interview,” a co-worker tells me when I’m 27.

“You’re kidding,” I say.

“No, really. That’s how you came across before we got to know you.” We laugh because, as it’s turned out, I’m often the first to poke fun at myself or crack a joke in a meeting, to let down my guard in hopes others will, too. I know what my co-worker means, though. No one has ever put it to me quite so starkly, but the shock I feel when he says the words ice queen is one of recognition.

“You have to smile at people,” my husband tells me. We haven’t been married long, not even a year. “You have to look people in the eye and smile at them when you meet them,” he says. “Otherwise they think you’re unfriendly. I know you’re uncomfortable with people you’ve just met, I know how shy you are, but they don’t. They don’t know you like I do.”

Slowly—it takes ten years or more—I teach myself to be the left side of my face when in company, congenial company, anyway.

The right side does have her place; she can be useful. The right guards her thoughts, whatever they may be, discouraging idle conversation and unwanted confidences. She isn’t rude or unkind; she’d give up the unused seat at her table. But a stranger might be wary of asking her for it. Seated next to her on a train or an airplane, other passengers don’t try to draw her into a dialogue. Without speaking, she makes it clear she doesn’t want to talk; she protects me—my privacy, my space, and my time. It’s she who ensures I can read my book uninterrupted.

* * * *

My eyes account for the difference. The left opens wider; its brow is half a centimeter higher than the right’s, enough that it alone is visible above the frames of most glasses. Because the left eye is wider, literally more open to inspection, it appears to welcome the curiosity of strangers, while the right remains comparatively hooded, defended if not defensive.

I smile at myself in the mirror, trying to discern if the woman I see is a friendly-looking person. Does the mood that divides my face account for the fact that the left corner of my mouth is curled, very slightly, upward into a smile, while the right corner is neutral and betrays nothing? I frown, as I do when I’m concentrating, to make sure the frown doesn’t look ill tempered. But what use is this? Any face I make for myself is self-conscious, artificial; it tells me nothing about how I might appear to others. My real self, the person the rest of the world sees, is someone I barely catch a glimpse of. But there is one trick I attempt to master. In my thirties, entranced by a friend’s ability to raise one eyebrow independently of the other—entranced by her in general, as she is very charming—I determine to teach myself how to do it, how to make a silent inquiry or convey disapproval more subtly than words allow. But I can’t get the hang of it. It never appears effortless or natural. Instead, I look as our dog does when she hopes to avoid a scolding, her head cocked to one side, her forehead wrinkled in anxiety.

* * * *

“If you make a face and the wind changes, it will stick.” My grandmother tells me this when I am very young. I believe her—I believe everything she tells me—and I worry: What if I am inside the house and I make a face not knowing that it’s windy outside? My face could be frozen forever in a grimace, or a look of surprise, my mouth a round O that I would never be able to close. I resolve to arrange my features into a pleasantly neutral expression and keep them that way, so as to defeat the unseen wind. But, no, this will never work. I can’t remain conscious of what my face is doing for even a minute.

* * * *

A winter morning, a Saturday. I am no longer a child but a woman of 30, and my grandmother is 91. Still, her power is such that I remember all her pronouncements: that if I were to step on a needle it would travel through my bloodstream and pierce my heart; that if I cross my eyes too many times they won’t uncross; that opening an umbrella inside the house or putting shoes on a table invites disastrously bad luck; that there are cases of people who never stop hiccupping and some of them die. I don’t believe any of these, not quite, but I don’t forget them, either. And her cautionary tales about snail fever turn out to be legitimate. Schistosomiasis is a parasitic disease, but you can’t catch it from garden snails, only from freshwater ones; the disease belongs to the Third World, in which she did grow up.

Standing in the hall outside her bathroom, I watch as she readies herself for a trip to her hairdresser and then on to the supermarket, where each week we walk slowly through the long aisles and she picks among the food and groceries, squandering as many minutes as she can on each choice: among brands of crackers; boxes of dry cereal; patterns printed on rolls of paper towels. It’s her only outing of the week and she looks forward to it, and to having my undivided attention for as long as my patience lasts. Still in her housecoat and slippers, she’s looking at her reflection in the mirror. She doesn’t know I’m there, as I’ve paused in the shadows, and am silent.

Outside the window, snow is on the ground, and light falls on the tiled floor in long blue-white bars. My grandmother is so small and bent that the mirrored door to the medicine cabinet can’t show her any more of herself than her face, and she looks at it for some moments, holding herself straight so that her chin makes it into the mirror’s frame.

She doesn’t see me in the hall outside the bathroom door: She doesn’t know I’m watching her. Slowly, she reaches forward over the sink and touches her reflection. “I’ve grown old,” she says, speaking to no one. “Suddenly, I’ve grown so old.” There’s wonder in her voice, mystification: How has she failed to notice what must have been happening for some time?

It’s a private moment, or I might move to comfort her. I might try to distract her from it. I might make tea or suggest we sit by a window where we can watch the people on the sidewalk as they pass before our house. These are among her favorite pastimes, making and drinking tea, watching strangers as they go about their business.

But it’s not a moment I can enter, only one I can destroy by intruding. I retreat up the stairs. I’ve seen the arrival of my grandmother’s awareness of her death, its imminence. I won’t forget what I’ve seen; I will carry it forward. It will become part of my apprehension of my own mortality, a thing so certain and unavoidable and even so natural that I imagine myself standing, one of an infinite line of women, generations going forward as well as backward. As if my grandmother or I, any one of us, were caught and multiplied between opposing mirrors, I see all of us reach forward to touch this harbinger of our deaths—the face, once a maiden’s, now a crone’s—trying to understand what we can’t understand, because how can Being grasp Nonbeing? How do we practice feeling it, the absence of ourselves?

* * * *

One day I look into my bathroom mirror and find that the person I expected to see isn’t there: She’s disappeared. This moment is divided by years from the day I watched my grandmother confront her reflection. I am now 37, my grandmother no longer living.

And they are connected.

More seriously depressed than I admit or even perceive, only a day away from what I don’t anticipate—a stay in a psychiatric hospital—not sleeping or eating, unable to work or think straight, I’ve gotten into the habit of comforting myself with a photograph that reminds me who I am, who I used to be. It’s a snapshot my husband took. I’m sitting with our two older children in a field of summer wildflowers, all of us bathed in light that looks genuinely golden, light that is a benediction. We’re smiling; the wind lifts my son’s pale hair into a halo. I use this picture to call me back into myself, reorient me to what is the essence of my life. It works well, too, until suddenly it doesn’t work at all.

The children are in school, my husband at work. I look at the photograph and don’t recognize anyone in it. Who are these people? I think. Who are they to me? I wait for the image to take effect, to reach past whatever is wrong with me, but nothing changes. I know I’m supposed to know them, us, but they’re no different from the people who come flattened under the glass of a newly purchased picture frame, a set of smiling strangers whose likeness you’re meant to discard and replace with a picture of your own.

I put my snapshot away in the drawer, walk into the bathroom, and stand before the mirror, staring. Apparently it’s possible, from one day to the next, from one hour to another, to slip out of one’s skin, one’s self, and land in a new, alien, and unrecognizable face.

Time passes, months, then years, and that bathroom mirror loses its power to frighten me. Still, I find it mysterious, and even wonderful, that there would be so stark and irrefutable—so apt—a symptom of nervous breakdown as a failure to recognize one’s own face.

* * * *

“Look,” my husband says. “That’s not her face. Her nose isn’t that short, and her mouth doesn’t look like that. And the eyes are the right size but not the right shape, not exactly.” We’re discussing a piece of art made by our older daughter, soon off to the Rhode Island School of Design—where she will paint, very well. It’s a life-size self-portrait, the final project for a course in advanced drawing. I think it’s very accomplished, I tell him. Especially I like the placement of the figure in the frame, and the way she’s rendered her hands, which, I point out, are difficult.

But my husband sees a problem: Our daughter, he concludes, has fallen prey to an idea of how she looks, and this idea is different from how she really looks. We continue to talk, about the drawing, about magazines and TV and movies, and how media may influence, even create, our daughter’s idea of her face. Perhaps she can’t see her face clearly, surrounded by a society so eager to tell her how she’s supposed to look—to define the contours of a perfect face, to direct attention to certain details over others, to make one face an icon, another unworthy of notice.

The idea stays with me long after our conversation ends. Each of us must see his or her physical self through a lens of various influences: prescriptive advertisements; critical remarks from parents or siblings or lovers; the human tendency to conflate physiognomy and character, mistaking a high forehead for intelligence or full lips for sensuality. Perhaps when we are young and enthralled by the faces of certain models or actors, we’re affected by something beyond their looks. We assume, of course, that powers are granted them by celebrity and imagine these might belong to us if only we looked as they do. But perhaps the psychic trajectory is more complicated.

Couldn’t it be that we project what we wish were true of ourselves onto the faces of famous strangers, finding heroism, self-confidence, dignity, genius—whatever qualities we aspire to possess—in the way they appear? Don’t we mistake their faces for illustrations of what we desire in ourselves? Don’t we try to emulate what we see, or begin to believe we look a little like these more nearly perfect avatars, these faces of who we might, with effort and time, become?

And wasn’t this what I lost or inadvertently broke ten years earlier, when I didn’t recognize myself: my idea of who I was, who I am. That lens of influences and aspirations, whatever apparatus would have guided my self-portrait: I must have lost what allowed me to bring myself into focus.

* * * *

Sometimes I’m startled by the face I see reflected back at me. Not the countenance I review each morning, unfolded from sleep, washed and subjected to quick analysis, to moisturizer, tweezers, and whatever corrections I can effect with cosmetics. That face is little more than a list of tasks to accomplish: teeth to brush and floss, brows to check for stray hairs, under-eye circles to mask with concealer, lips and lids and lashes to color. I’m speaking rather of the face I see inadvertently, cast back at me in a shop window as I hurry through errands. Who is that woman? Whose dark and angled glance meets my eye in a department store mirror I don’t anticipate? She looks to be a solitary soul, the face who catches me unaware; she looks anxious and driven. A face I glimpse rather than see.

I catch her; she flees—the right-hand me with the hooded eye, the face I thought I banished and summoned at will, using her to silence garrulous fellow travelers or defend me against the occasional boor. Apparently she isn’t obedient but emerges according to her own agenda, knifing efficiently through sidewalk crowds, both punctual and eager to avoid the touch of strangers.

And me. As much me as the left-hand self with her wide, dreamy eye, the self I own more readily because she’s attractive, flirtatious, quick to smile, to laugh. The lines she’s traced on my face are lines I like, radiating out from each eye. Different from what the right-hand woman has etched into my forehead.

Perhaps the unseen wind did change one storm-tossed day when, heedless of the consequences, I was looking as I felt: dark and brooding, overcast by fears. That face stuck, and others did as well—the one, for example, I wore when sitting in a field of wildflowers, golden. My grandmother didn’t say I’d have only one face. She didn’t say it couldn’t happen again and again with every shift in the wind. That was my misunderstanding.

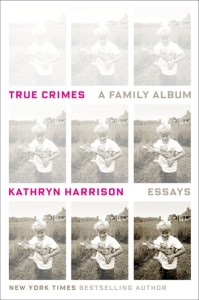

From TRUE CRIMES: A FAMILY ALBUM. Used with permission of Random House. Copyright © 2016 by Kathryn Harrison.

Kathryn Harrison

Kathryn Harrison has written the novels Thicker Than Water, Exposure, Poison, The Binding Chair, The Seal Wife, Envy, and Enchantments. Her autobiographical work includes The Kiss, Seeking Rapture, The Road to Santiago, The Mother Knot, and True Crimes. She has written two biographies, Saint Thérèse of Lisieux and Joan of Arc, and a book of true crime, While They Slept: An Inquiry into the Murder of a Family. She lives in Brooklyn with her husband, the novelist Colin Harrison.