On the Igbo Art of Storytelling

Ikechukwu Ogbu Heeds an Ancestral Calling

In December, 2013, my younger brother and I traveled to our village in Igboland, southeastern Nigeria, to spend the Christmas holiday with our grandmother. Every day there, we’d read the novels we’d travelled with, watch local football, visit extended family members, trek to our grandmother’s farm to harvest cassava, and then bathe in the village stream. On Facebook, I’d keep a journal of these events, fictionalizing certain aspects to create the aura of an adventure.

I was twenty-two, my younger brother seventeen, and I was in my final year in the university, studying English Language and Literature. Over the last few months, I’d been telling myself that I had to become a writer; I could only be a writer. After all, hadn’t that been why I’d written so many stories, as a child? Hadn’t that been why I’d applied to study English Language and Literature though everyone else said I’d make an excellent lawyer? Hadn’t that been the reason I’d recently completed a bad novel, but a novel nonetheless? Still, this was Nigeria; the future for most writers was bleak. But I was going to succeed. Some way, somehow, I’d make it as a writer. What I did not then know, of course, was that the art of telling stories ran in my bloodline; that writing wasn’t just another job available for me to try my hands on. It was instead something I had a calling for, just as a priest might speak of his vocation. I would know this the night I had the most heartfelt conversation with my grandmother.

*

That night, my brother and I had just returned late from a visit. We were tired, about to go to bed, so went to bid our grandmother a good night in the adjoining building to our father’s.

We met her outside, a lit kerosene lantern by her side though the moon was out. Seated on a wooden chair and bent forward, she picked brittle bones from a bowl of dry fish. Tomorrow morning, she’d prepare a pot of ofe egusi with the fishes.

“My children,” she said, looking up, “is it sleeptime already?”

We said it was.

“Ngwa nu, sleep well,” she said.

Immediately, my brother turned and left to go to bed; I didn’t. Something in my grandmother’s eyes had caught my attention: a dilating of eyes to bear the weight of longing, a look I often see on my father’s face whenever he’s itching to tell a story.

My father, you see, is a compulsive storyteller. All my life, I’ve always known him as a man incapable of being quiet when people are around him. He’ll initiate a conversation and anxiously stoke the fire. There was this once when my mother, tired of his non-stop talking, asked if he’d be quiet and, defending himself, my father said, “Shouldn’t I talk when I have the mouth for it?” To shut him up, my mother turned to us and said, “Do you know your father talks in his sleep?”

My mother (now late) told stories, too, but she was a reluctant storyteller. She approached it as one might a chore, something, as an Igbo woman, she owed her children, not something she enjoyed doing. She preferred written literature, and by the time I was ten and she’d noticed I couldn’t stop rereading Lambs’ Tales from Shakespeare, she encouraged me to read some of her novels, including Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and Cyprain Ekwensi’s An African Night’s Entertainment. So, as a child, I was fortunate to have about me a perpetual swirl of stories. Yet, none of these stories, as interesting they were, could have prepared me for the thrill and connection I would feel in the presence of my grandmother, that night.

The earth was quiet, asleep. The moon shone brightly. Crickets chirped about us. The kerosene lantern burned steadily.

After sitting with her for a while, she started to talk, threading through narratives. How, as children, my elder brother avoided her while I clung to her and refused to be pulled away as she sang folk songs and told stories. This made me laugh, as my elder brother, a resolutely practical man, is the opposite of an artist and has never had the patience for long, meandering talks. But it wasn’t for this anecdote that that night would continue to hold an extraordinary meaning for me. It was, quite simply, the story of the demise of a market.

Administratively, our village is divided into several quarters. Ours is called Onu Nkwo, which means “in front of the Nkwo market.” Next to ours is Onu Afor, which means “in front of the Afor market.” But while Onu Afor has an actual Afor market, Onu Nkwo does not have an Nkwo market yet we are supposed to be the quarters in front of it.

My grandmother laughed at my query, tapped her snuff box, turned it open, took a pinch, filled both nostrils, then sneezed. Her voice took on a cheerfulness, excited about the story she was about to tell.

Well, she said, there in fact used to be an Nkwo market (she described the old location) but it was one of the things we lost to the Biafran War of 1967-1970.

During the war, she said, it became impossible for markets across Igboland to open because these markets, held in wide open spaces, became conspicuous targets for enemy fighter jets. So the Nkwo market in our quarters was relocated to underneath a canopy of trees in the forest, and conducted in a kind of unnatural silence no one had ever known a market could be conducted in.

After the war, Igboland had lost so much that the people of my village, defeated and having just returned from the forest they’d gone to hide to avoid air raids, did not have the means nor the willingness of spirit to rebuild the Nkwo market that had been bombed to a rubble.

That night, as my grandmother told this story, she mentioned how, when my father took her to Enugu, years after the war, she had to stop at a busy junction to stare and marvel at the largeness and resilience of the human race, for she’d seen so many deaths she couldn’t believe there were still so many people in Igboland.

By the time she stopped talking, the time was about 2 am and we’d been sitting there for more than four hours. The earth was quiet, asleep. The moon shone brightly. Crickets chirped about us. The kerosene lantern burned steadily. And for the first time in my life, I experienced transcendence.

Seated there in front of my grandmother’s house, the small bush in front of us seemed to recede further and further until I felt that around us was an interminable stretch of vast land, desert-like, but as if paved with fired clay, inhabited by only my grandmother and I, and she’d brought me there simply to pass across this single piece of information: that I was born into a lineage of storytellers, a tradition I was to uphold—a calling; not just another job available for me to try my hands on. That from my great-grandmother, Igwe Nwa Njoku—who I’d been told could never keep herself from talking—the mantle of storytelling had changed hands until eventually dropped on to me. That this was who I was, condemned—as those who came before me were, one could say – to a life where, once I started talking, it was only with a learned self-consciousness that I could now keep myself from continuing unabated. But unlike my predecessors, I would mostly tell my stories through written words.

To this day, I am certain my grandmother would have carried on talking had my uncle, sleeping in the third building in the compound, not heard his mother’s voice, at that time of the night, talking to someone. He came out to investigate and was not happy his mother had kept me up. Turning to me, he warned that if I indulged his mother next time, she’d keep me up until dawn.

The importance on storytelling asides, added regard is given to polish: for how beautifully one can turn phrases, invent metaphors and spin a jolly good yarn in the most captivating manner.

I did not like that he scolded his mother, my grandmother, and I was certainly affronted by how he treated me like a child, as if I did not know what was good for myself. Anyway, the most important duty of the night had been done.

*

The Igbos are a tribe of storytellers. From Chinua Achebe to Buchi Emecheta to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, young Igbos are raised on a healthy diet of stories. Here’s how Chinua Achebe puts it in Things Fall Apart: “Among the Igbo, the art of conversation is regarded very highly and proverbs are the palm oil with which words are eaten.” So the importance on storytelling asides, added regard is given to polish: for how beautifully one can turn phrases, invent metaphors and spin a jolly good yarn in the most captivating manner.

A landscape representation of this are the obodos spread across Igboland, what people now call village squares (they are neither squares nor are they sectioned off in the general sense of a town square).

An obodo (or otobo or ilo, as it’s called according to various Igbo dialects) is a vast arena where benches are placed under a network of trees. Here, people would gather for meetings and to tell stories, especially under moonlight, a phenomenon now popularized across Nigeria as Tales by Moonlight, after a Nigerian Television Authority (NTA) program of the same name, created in 1984 by Victoria Ezeokoli.

This storytelling culture also goes to the heart of Igbo music. Indigenous Igbo music—combining instruments like vessel drums, metal gongs, flutes etc, and played to an energetic beat—is often used to narrate a series of events. Think of something like Immortal Technique’s Dance With The Devil or Ludacris’s Runaway Love featuring Mary J. Blige.

And also, in the 1970s, when Igbo highlife started to gain mainstream popularity, musicians like Osita Osadebe, Oliver De Coque, Morocco Maduka, etc, would, leaning heavily on guitars and pianos, tell stories across verses. Usually, the chorus, steeped in Igbo philosophy, would reecho the theme of the narrative.

In one of the most popular songs of this genre, Prince Morocco Maduka, in “Ochuba Aku,” tells the story of a soldier who returns from war, poor, and crazed with a desperation to be rich, kills a girl for money-making ritual. Though he becomes rich, he finds that he’s unable to father a child, even after successively marrying five women. This leaves him despondent as he cannot understand the point of wealth when there are no children to enjoy it.

In the chorus of the song, the musician sings, again and again, that the world is no one’s home; that no matter one’s wealth or achievement, we’re all journey men who’d one day return to where we came from.

This is the music—and by extension, the storytelling culture—that I grew up immersed in. And so every day, sitting in front of my laptop to write, I sometimes fear that I would not be able to produce anything as profound as I’ve been culturally equipped to. But it’s not for the absence of fear that people make great art, it is for the decision to not focus on fear but to give one’s time and attention to one’s work, each day at a time, each moment at a time.

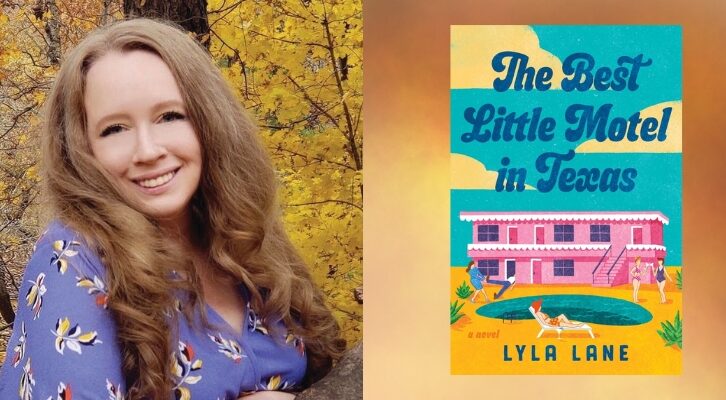

Ikechukwu Ogbu

Ikechukwu Ogbu is a Nigerian writer who holds a BA in English and Literature from the University of Benin. His fiction has appeared in The Threepenny Review and he's currently working on his debut novel.