The seats are wooden, the train cars date from before World War II, and we creep along like a snail. The landscapes drift by with a strange indolence. From time to time, the train stops. We look out the windows and breathe in air polluted by the locomotive’s smokestack. People clamber aboard laden with baskets, sacks, even live roosters. They smoke foul tobacco. I cough and turn away.

I think about the meetings we held over the past few months: useless, unproductive. At our age, it’s normal for us to want to change things, and we aren’t doing anything wrong. We talk for hours, discussing the hard facts of the situation. We want to fight against injustice, repression, the lack of freedom. What could be more noble? Most of us don’t belong to any political party. One of us is a Communist, it’s true, or at least he’s always championing communism, but we don’t try to find out what that really means for him. He hates America.

Me, I adore jazz and American movies, so I don’t understand his stubborn attitude. He thinks everything that comes from the United States is bad, harmful, untouchable. He doesn’t drink Coca-Cola, for example. That’s his way of expressing his anti-Americanism. Well, a little glass of Coke, I like it, especially in the summer. That’s hardly enough to make me feel complicit in the atrocities committed by GIs in Vietnam.

The train gently gets going again. My brother has dozed off. The peasant with the roosters stinks. I even think I see a louse or a flea on the dingy collar of his old shirt. He takes out a long pipe, packs it with what looks like tobacco, and lights up. It’s kif. He smokes quietly without even wondering if it might bother us. I feel a migraine coming on. I’m prepared for this: when I get an aspirin from my bag, the peasant holds out a bottle of water, and I wish I’d brought a glass along too. I thank him and swallow the tablet.

I stand up and walk a little way along the aisle. In the distance I can see a shepherd taking a nap under a tree. I envy him. I tell myself he has no idea how lucky he is. There’s no one to punish him, and I know he hasn’t done anything, but personally I’m innocent as well and here I am on this miserable train headed for a barracks where I have no idea what’s going to happen to me!

I see a peasant woman go by and think of my fiancée. That hurts. Zayna didn’t come to say good-bye to me before I left. And I’d even called her. Her mother had answered the phone coldly. When I told Zayna what was happening to me, she didn’t say anything, or rather she sighed, as if I were annoying her. “Good- bye,” she told me, and hung up. I’m in love with her, I think constantly about when we met, in the French Library. Our hands had reached for the same book, The Stranger by Camus.

“I have to write a report about it,” she told me, and I’d quickly replied, “I could help you, I’ve already studied it.” That’s how we came to meet several afternoons at the Café Pino, rue de Fez. We talked a long time about this story of an Arab murdered because of the sun, or sorrow. “His mother dies,” she’d say to me, “and he doesn’t know exactly when? He’s an unworthy son . . .”

We live in a system where everything is under control. Fear and suspicion are pre-installed.I too didn’t understand how a son could not be sure about which day his mother died. After all this astonishment, we looked at each other like Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman. I often accompanied her all the way home. One evening, taking advantage of a power outage, I stole a kiss. She clung to me, and it was the beginning of a love story in which everything seemed momentous. We had to hide to love each other. She preserved her virginity and I made do with caressing her. Darkness was our accomplice.

There was an excitement about these furtive embraces that left us trembling. Rich in feverish uncertainties, our love intoxicated us. Impossible to forget, those moments that played out later in our dreams. The next day, we’d tell each other about our night. We were giddy and happy. To all that, His Majesty’s police were about to put a brutal and definitive end.

The train enters the station in Meknès at around seven that evening. Torrid heat. The last bus between Meknès and El Hajeb left a half hour earlier. Spending the night in this unfamiliar city is a discouraging prospect. My brother finds an inexpensive little hotel. The guy at the reception desk is blind in one eye, hasn’t shaved for a few days, and spits on the floor with a sharp little sound, it’s a tic. He makes us pay in advance and hands over a large key, saying, “No whores allowed.”

I look down, embarrassed in front of my big brother. A room with two beds. Dirty sheets. Randomly stained with blood. We look at each other without a word. No choice. If you’re poor, you can’t be fastidious about soiled sheets. My brother produces a roast chicken from his bag: our mother has thought of everything. A big loaf of bread, some Laughing Cow cheese, and two oranges. Sitting right on the floor, we eat without comment. Looking to wash our hands, we realize that there is neither sink nor toilet in the room.

Everything is out in the hall and repulsively foul. We stare at one another, wild-eyed, then look down, mortified. We go to bed completely clothed. The mattresses sag in the middle. They’re almost hammocks. All we need are trees, springtime, the cocktails, and the green olives. I don’t sleep. The migraine has settled in. I sit on the edge of my bed. Something is pinching the back of my neck. I scratch and find a bedbug. I squish it with my fingers. It stinks.

Will I be able to forget that odor of blood and rotten hay? My brother is awakened by the noise and bothered by the smell. I go down the hall to wash my hands. The water is just a dribble. The washbasin, broken; the cracks are filled with crud. I return to the room and sit back down on the edge of my bed. Although feeble, the light is enough for me to spot two more bedbugs on the pillow. I shake it.

They fall; I squash them with my shoe. My brother joins the hunt for the smelly little bugs. For the first time all day, we laugh, even though we feel like crying over our fate—because after those wretched policemen delivered the summons to our house, my parents fell ill.

One day, just like that, men come knock at your door in the name of the government, you don’t dare verify their identity, they’ve come for a simple routine verification of documents. “We just have a few things to clear up with your husband,” they explain; “he’ll be back in an hour or two, don’t worry.” And then days go by and the husband does not come home. Despotism and injustice are so pervasive that everyone lives in fear.

My father dreams of a system like the one in the Scandinavian countries and often talks to us about Sweden, Denmark, and democracy. He also likes America, where even if someone assassinates the presidents, revenge is not taken on the entire population. “John Kennedy died; his murderer was shot. That’s all!” he said to me one day.

In the middle of the night, I begin to feel tired. My head feels hot, I’m sweating. I open the window; mosquitoes fly in by the dozens. I close it. I try to think about a lush green meadow with me sitting on a bench chatting with friends; in the distance I see a girl in a summery dress coming toward me . . . it’s a dream. A fresh bedbug bite startles me. I decide to get up.

I rummage through my bag and take out the cookies my mother made. I eat two of them. Crumbs fall to the floor. Ants, on the alert, come running. It’s amusing to watch them. They entertain me. My brother has managed to get back to sleep; he’s snoring. I whistle but that doesn’t help: he changes position and keeps snoring. I study him carefully and notice the beginning of a bald spot. He’s 12 years older than I am. He is a generous and cheerful man.

He got married when very young to a cousin. He finds politics interesting, but like my father, he’s careful when he tackles sensitive subjects. He speaks in metaphors, mentions no names, but everything he thinks is written on his face. He is the one who explained to my parents that this summons for military duty was a punishment. My mother began to cry. “What has my son done to be punished? Why shut him up in a barracks? Why ruin his youth and destroy his health, and mine as well?”

My father told her, “You know perfectly well why, he meddled in politics!” My mother, indignant: “What’s this ‘politics’? Is it a crime?” Before my astonished eyes, my father then launched into a lecture: “In Arabic, politics is Siassa, which comes from the verb sassa meaning to direct, to lead an animal, a mare or a donkey, for you must know how to guide the animal so that it gets where you want it to go. To engage in politics is to learn how to control people.

Our son tried to learn this profession, he failed, is being punished for it, would have been congratulated in another country, but in ours he is permanently discouraged by being made to regret having wandered into a domain reserved for those who have the means to exercise power and who do not put up with those who contest this. There, it’s quite simple. Our son made a mistake: he strayed into an area that does not belong to us.”

Actually, he was trying to convince himself of what he was saying. My father abhors injustice. All his life he has denounced it, has fought against it as best he could. He knows that in this country, battling injustice can end quite badly. He’d been traumatized by the arrest and imprisonment of his nephew, who had dared to say in public that “corruption in this country begins at the top and goes all the way down to the doorman.”

Three days after going to see his nephew in prison, he was visited by two men who bombarded him with questions. At some point, one of them said, “You have children, boys, don’t you?” My father understood instantly: he had to keep his head down. It made him sick. That evening, he had a fever and went to bed without a word.

The next day, he called my older brother and me together to tell us, “Be very careful: no politics—this isn’t Denmark, also a monarchy, but here it’s the police who rule, so think of my health and especially of your mother’s, her diabetes might get worse, so no meetings, no politics . . .”

We replied that in any case the powers-that-be could hurt us even if we avoided politics. We live in a system where everything is under control. Fear and suspicion are pre-installed. A cousin of my father’s who frequented the Information Bureau warned him that I’d been seen having coffee with a leader of the student movement in Rabat. Having a coffee! A crime already noticed and archived.

As for me, at the time I had absolutely no idea of the extensive security network in Morocco. I busied myself with the Ciné-Club in Tangier with a complete feeling of impunity. I saw nothing political about the club at all. The very day after we showed Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, however, I am summoned by the police. I’m 15 years old and quaking, because it’s the first time I’ve set foot in a police station.

The guy, maybe an officer, says to me, “Do you know this film is an incitement to rebellion?”

I’m speechless. Then I get a grip.

“But, not at all, monsieur. This film portrays a historic event that has nothing to do with our situation, it’s a work of art. Eisenstein is a great cinematographer, you know.”

“Don’t feed me guff, I know about Eisenstein. I once wanted to work in film production—I’d even registered at the Institut des hautes études cinématographiques in Paris, but my father died in an accident, so I had to interrupt my studies, and since the police were recruiting, I signed on. Right, listen up: you’re lucky I love movies. By the way, what’s the next show at the Ciné-Club?”

“Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring.”

“Very good choice. That one, at least, isn’t political!”

He suggests a few codes for me: “Everything’s fine” means things are going badly; “Everything’s perfectly fine” for “Everything’s going really badly.”By five in the morning, I’m nodding off. I no longer feel the bedbugs, mosquitoes, and so forth. The ants have disappeared. I fall asleep. No dream, no nightmare. At eight, my brother awakens me. We have to go. We eat breakfast in the café next door. Terrible coffee, but excellent mint tea, some fritters. “Careful,” my brother tells me; “this cooking oil must be a year old!” It’s not as noxious as the bedbugs.

The fritters remind me of my childhood in the Medina, the “old city” part of Fez. Once a week, on the day we went to the hammam, on our way home my father would buy us fritters for our breakfast. We’d dip them into a bowl of honey. It was unforgettably delicious. There were crumbs and dead bees in the honey pot. My brother and I would have fun cleaning out the pot, laughing and licking our fingers.

A beggar holds out his hand; I give him my fritters. He devours them, another beggar arrives, I give him my glass of tea; he tells me he’d prefer a cup of coffee. Bees and flies whirl around our heads. Meknès is waking up. A mint seller passes by shouting, “Good and fresh!” It’s the mint of Moulay Idriss Zerhoun, the patron saint of Volubilis, near Meknès. After that long and horrible night, I’m ready to brave anything.

We look for a taxi to go to El Hajeb, a half hour’s drive away. People are waiting, beggars roam around, a barefoot boy picks up a cigarette stub from the ground and gets chased by a bigger boy. Some lost tourists are being pestered by a swarm of fake guides, whom a policeman chases away with reproaches: “Shame on you! You’re making our country look bad!”

Someone points out to him that the country’s image is fairly lousy any way you look at it, from the inside or out, then runs away. “I know you!” the flic yells threateningly, “I know where you live, I’ll get you—you insult the country and its king, you’ll see, you’ll pay dearly for that!” He begins shouting our patriotic slogan: “Allah, Al Watan, Al Malik!” God, the Nation, the King.

The crowd is laughing; the policeman now seems a little crestfallen.

A taxi arrives. People rush over. The flic calls for order, then tells my brother, “Get in, you’re not from around here, right?”

So we’re now scrunched together on the front seat. The plastic is torn, revealing foam of an indeterminate color. The driver smells of rancid butter; he’s just finished breakfast. He lights a truly foul-smelling dark-leaf cigarette. Four people are in the back: an old man in a maroon djellaba, a peasant woman wrapped in a white haik, her son, and a soldier on leave. The driver says, “Pay up.” Everyone does.

As we drive along, the discussion centers on the local soccer team. My brother, born in Fez, dares to defend his team, Le Mas. That casts a chill over the taxi. The passengers must be wondering if he might be crazy, vaunting the archenemy of the Meknès team. The driver changes the subject by discussing the price of tomatoes. That calms everyone down.

The soldier tells him to pick up the pace a bit: “I’m going to get in trouble with Akka.” Akka seems to be someone important. “You poor fellow!” the driver tells him. The old man sitting behind him chimes in: “Akka is very tough; he frightens everyone—even those who have never met him.” The driver nods in agreement.

El Hajeb was originally a military base. My brother looked up its history: Sultan Moulay Hassan, he tells me, had constructed a kasbah in this village to repel the rebel forces of a Berber tribe, the Beni M’tir. The army took over the base and made it into one of the main garrisons of the realm. It was a difficult period, the so-called Siba, which means at the same time revolt, panic, disorder, and chaos.

My brother remarks to me in French: “You see how rich Arabic is! The word Siba leads you to so much history.” The driver points out to him that he would do better to speak in Arabic. My brother excuses himself and says nothing more.

The driver drops us off a few yards from some military trucks. I think I see pity in the look he gives me. “May God protect you!” are his parting words. The soldier from the taxi begins to run; we see him salute an officer and disappear.

Before we proceed to the entrance gate, my brother hugs me and I can tell he is crying. He whispers, “My brother, I’m going to leave you in the hands of barbarians without even the right to know why or for how long these people will keep you here. Be brave and if you can, send us news. Write ordinary things, we’ll read between the lines.”

He suggests a few codes for me: “Everything’s fine” means things are going badly; “Everything’s perfectly fine” for “Everything’s going really badly.” “The food is as good as Mama’s cooking” means things in that department aren’t great either. Lastly, for trouble, I must write, “Spring has paid us a visit.” I reassure him, then thank him for coming with me all the way to the camp gate.

__________________________________

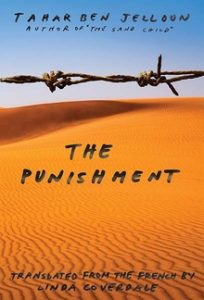

From The Punishment by Tahar Ben Jelloun, translated from the French by Linda Coverdale. Published by Yale University Press in April 2020 in the Margellos World Republic of Letters series. Originally published in French by Editions Gallimard. Reproduced by permission.