On the Humorous Surrealism

of Mimi Parent

Penelope Rosemont Remembers Her Friend,

the "Aeronaut of Invisible Spaces"

Why are summer mornings so crystal clear? Sparkling, bright, still: Is it a quality of the air or of the light? Or of the mind in exhilarated expansion? I remember a summer morning, one of countless similarly delicious mornings when the brilliance of the sun brought out in glowing detail trees, boats, and houses across Fox Lake—more than five miles away—just as it searched through the transparent water revealing every ripple, every pattern of the golden sand on the bottom, every pebble, and fish, seemingly suspended and lighter than air, their dark shadows standing at their side.

These mornings had a magical stillness about them and a sense of being delightfully becalmed, suspended in an ocean of fragrant air, motionless, stranded—but stranded precisely at the most glorious place in the world. What more could one wish for than this perfect delight, not timeless but time-free?

In such moments, far outside the hubbub and petty concerns of daily life, the imagination begins to dance, first slowly, then madly—like bugs skating on the water—until every molecule of oneself is alive, and that ability to see, as if forever, with unlimited vision, is the same as to live forever, in infinite extension.

Then, suddenly, from a branch overhanging the glistening water, a bright blue flash—a loud splash—as a kingfisher throws himself into the clear water as droplets of crystal like tiny glass magnets fall in showers of a shattering drama back into stillness.

In the art of Mimi Parent, among the most original and powerful of our time, I find the same magic transparence and delight of summer morning, along with the piercing audacity, the intense underlying passion of a kingfisher set to dive.

There are people we meet who, without realizing it at all, have a profound impact on us—an influence that does not diminish over time but lasts and grows. I first met Mimi Parent on a night like no other: New Year’s Eve 1965 in Paris. Franklin and I had just arrived there to look up André Breton and the younger generation of surrealists, and had been invited by the surrealist writer Robert Benayoun to their New Year’s party, which was also in part a celebration of the International Surrealist Exhibition that had just opened at the Galerie L’Oeil. A marvelous, complex series of chances had conspired to get us to Paris at this particular moment; had we arrived sooner or later we might well have missed everything.

The party was held at the Théâtre Ranelagh near the Bois de Boulogne. One of the oldest theaters in Paris, the Ranelagh was quite a spectacular place in itself, but that night the marquee outside was dark: the party was strictly reserved for the group and its friends. The surrealists of Paris greeted us warmly, with special affection on the part of Mimi and her companion Jean Benoît, who kissed us on both cheeks and wished us a hearty Bonne Année!

Mimi Parent, who seemed to be in her twenties, was admirably flamboyant, splendid, brilliant. She was also patient with my rudimentary French, and kind enough to take the time to help me follow the boisterous conversations at surrealist gatherings, beginning that very night. We immediately became good friends. Mimi herself had come to Paris from Montreal in 1948, and spoke English and French perfectly. Since 1959 she had been a dynamic, exhilarating force in the Surrealist Group.

As we met I thought of her drawing, which I had just seen at the Galerie L’Oeil: Titled En Veilleuse (A Lamp in the Night), it reveals a woman with long flowing hair, dressed in carnival costume, standing on the saddle of a horse; on the ends of her balance-bar she carries the sun and moon. This exquisite and defiant picture serves notice that only poetry can rescue cosmology from positivism.

The exhibition also featured a large piece—large enough to walk through—titled the Arch of Defeat, a détournement of France’s monument to militarism (and top tourist attraction), the Arc de Triomphe, now furnished—courtesy of Mimi Parent—with a wooden leg.

Clearly, Mimi’s love of the Marvelous and her knack for subversion are but two sides of the same magic apple.

The International Surrealist Exhibition, L’Écart absolu (Absolute Divergence), was inspired by the visionary writings of Charles Fourier, the great utopian socialist and proponent of the theory of Passional Attraction as a new means of understanding human beings and of discovering the true bases around which a new, non-exploitative society could crystallize. Mimi’s art, following her own passional attractions, dazzlingly actualizes the poetry and humor of Fourier’s revolutionary ideas, for her whole outlook is animated by a vital ethic of desire. Each of her works affirms Fourier’s observation that “Attractions are proportional to destinies.”

Aeronaut of invisible spaces, explorer of the oneiric stratosphere, sorceress of luminous laughter, Mimi is a bird-woman who can travel equally well in the air, beneath the water, and even through fire.

On another trip to Paris in 1970 I had the pleasure of seeing many of her paintings at her apartment on the avenue de l’Opéra. What a strange experience when we arrived there, for to reach Mimi’s place we had to climb two stories of a tall, ancient, curving staircase. It was the staircase of dreams for me—the same as the one pictured in a childhood book of mine, The Snow Queen; in the story, a raven perched on the newelpost and the shadows of long dead ladies and gentlemen flitted up and down the stairs. Mimi’s stairway seemed to me a harbinger of untold wonders, and I was not disappointed.

Mimi showed us her paintings, bringing them out one by one, and commenting on them playfully, with imaginative flair. At that time she did not show her work in galleries, and had no interest in exhibiting except in group shows organized by the surrealist movement itself. Her adamant refusal to be part of repressive society’s official “art world”—in glaring contrast to the commercial ambition and greed of so many artists—seemed to me worthy of the greatest respect. But I protested, arguing that she should not deprive the world of the right to see these splendid works, that she must find ways to show them, because they were meant to inspire people and to change their lives, to counteract the rampant miserabilism of our time, and to help usher in the “New Amorous World” announced by Fourier.

Mimi’s paintings cast their own unique glow—irresistible, and yet recalcitrant in the best sense of the word. In her art as in her life, she has always preferred the stronger passions. It has always been her pleasure to take risks that few painters today have been willing to take. In the painting she selected to be shown at the 1976 World Surrealist Exhibition in Chicago, a bird of fire emerges from a dark figure in a roadway lined with black trees and breaks through the green darkness—blazing wings about to soar, a flame-feathered athanor of desire, ready to swoop. Here again Mimi assures us that only poetry, and the awareness that poetry ignites, can enable us to face the abyss. If the language of dreams did not exist, Mimi would have invented it for us!

The presence of birds in her paintings, which cannot be mistaken for a mere “motif,” reminds us that in Fourier’s Universal Analogy the bird is “the creature who rises above all others.”

Another painting, aglow with four different kinds of radiance, portrays a gray sky filled by a gray eagle whose talons reach through the very walls of the Bastille to clutch two frilly female dolls. It is called Les Très Riches Heures du Marquis de Sade, a play on the famous Very Rich Hours of the Duc de Berry. It is Mimi’s tribute to Sade’s vision of freedom that defies convention and stretches the limits of the imagination.

I think of Mimi as a great magician, of the most elegant kind. It is easy to imagine her wearing a tuxedo, standing stage-center under a spotlight, pulling rabbits out of hats and making people disappear into cabinets. Is this because on that New Year’s Eve night when we first met she was in fact wearing a top hat and tux with tails, exactly like a stage magician? No doubt—but she was also wearing black fishnet stockings on her long legs and dancing in a mad parody of a 1920s chorus line.

A drawing of hers from the 1980s, titled A Large Rabbit Frightens Madame Recamier, shows a large white rabbit—just the kind that magicians pull out of hats—seated on Madame Recamier’s famous couch, while Madame herself hides under it. Here we find Mimi merrily negating a museumified icon of fine art and a bourgeois ideal of womanly beauty, both of which have long been tiresome clichés. Overturning the platitudinous image and welcoming the intrusive rabbit, Mimi shows us that sometimes total upheaval is the best of all possible harmonies.

Humor, often black but sometimes rose or robin’s-egg blue, is in fact central to Mimi’s art. Her 1989 drawing, Qui part? (Who’s Leaving?), reproduced on the cover of my anthology, Surrealist Women, shows three female figures (the three fates, or graces?) sitting on a trapeze, and suspended just above a railroad track. Mimi’s title imperiously recalls Gauguin’s three questions “Where do we come from? Who are we? Where are we going?” and her demand is addressed to all three.

Which one is about to leave? The one with skirt and legs for a head? The one wearing a stern and anonymous black mask? Or the one whose upper body is the smoking engine of a railway train? Or is it all three? Or an interactive, dialectical blend of beings in constant motion, performing for her/their own pleasure (and, perhaps incidentally, everyone else’s) on a circus trapeze bar?

Implicit in this drawing are other questions, no less provocative: Why can’t one live more lives, have more identities? Why settle for conventional limits? Implicit too is the demand to resolve that dilemma of women and men in modern society, who find themselves trapped in the loneliness of narrow, stereotyped and ultimately ridiculous roles and patterns of behavior.

In any event, Mimi’s baggage is packed, the rails lead into the future, and action is imminent!

The range of Mimi’s work is impressive: In addition to the paintings and drawings for which she is best known, she has also made surrealist objects, collages, and fabrics, to say nothing of the important role she has played in the elaboration of surrealist group shows: her crypt devoted to fetishism, for example, at the 1959 International Surrealist Exhibition in Paris. In her most recent works, her tableaux-paintings, which are also among her finest, the restless activity of the imagery, like prime matter in the alchemist’s cauldron, overflows the frame and leaps to our eyes. These perilous dramas, touched by the Gothic and even more by Umor, are stunningly confrontational: They pose the most urgent questions and refuse to take anything less than the viewer’s own unfettered imagination for an answer.

Mimi’s famous word of warning, “Knock hard, life is deaf,” is indispensable advice for anyone who seeks to follow a nonconformist path, to venture into a different life. And it is a very special pleasure to follow the paths she herself has opened for us, to enter the worlds she has shown us, and to see them through the magic lucidity of Mimi’s eyes.

Aeronaut of invisible spaces, explorer of the oneiric stratosphere, sorceress of luminous laughter, Mimi is a bird-woman who can travel equally well in the air, beneath the water, and even through fire. According to Surrealist Intrusion in the Enchanters’ Domain (the catalog of the International Surrealist Exhibition in New York, 1960–61), she herself lived “surrounded by birds.” She knows their language and their secrets: especially the secret of freedom.

This is the art of Mimi Parent: a transcendental ornithology that illuminates the secret concealed in the old saying, free as a bird, and lets us be carried away with it.

__________________________________

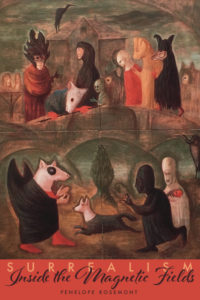

From Surrealism: Inside the Magnetic Fields. Copyright 2019 by Penelope Rosemont, reprinted with permission by City Lights Publishers.

Penelope Rosemont

Penelope Rosemont, an advocate for the recognizing the importance of women surrealists, edited Surrealist Women: An International Anthology (University of Texas Press, Austin, 1998). Her paintings appeared recently in the exhibitions: "Revolutionary Imagination: Chicago Surrealism from Object to Activism," 2018 and "Dada Chicago" 2016. She continues to be active in the surrealist movement and is in touch with surrealist groups in Madrid, London, Prague, etc. Her book of essays Surrealism: Inside the Magnetic Fields will be published Fall 2019 by City Lights Publishers in San Francisco.