On the Hollow Spectacle of Attaining American Citizenship

José Orduña Takes on Oath, Shudders

A bald judge in robes walks in from behind the stage. Eleven middle-aged white men follow him out, wearing red button-down shirts. They assemble into a small semicircle on the left side of the stage, and one man introduces them as members of the Harmony Hawks, a seventy-member barbershop chorus. Several of the men resemble Kenny Rogers, and others have the blunt look of Bavarian stock, all foreheads and thick fingers. The judge reads an introduction, which is really just a list of the requirements we’ve met in order to be sworn in as United States citizens here today. They increase in absurdity, reaching an apex when he tells us that we’ve established our good moral character during the legally mandated statutory period, have demonstrated our attachment to the principles of the US Constitution, and have shown ourselves to be well disposed to the good order and happiness of the United States. We’ve demonstrated, unless exempt by law, the ability to read, write, and speak words in ordinary usage in the English language. We have demonstrated our understanding of the fundamentals of the history and government of the United States.

There are forty-seven of us. I am one of three Mexican nationals. I open my white envelope. Inside is a small US flag made of thin vinyl. There are a few other papers inside that I don’t retrieve. Looking around, others have also pulled out their tiny flags, not knowing what we’re supposed to do with them. The Harmony Hawks begin “God Bless America” in the hammy barbershop style, which I can usually walk away from if ever confronted with it, but here I’m stuck. The singers smile between phrases, and when they’re done they look happily upon the crowd. But any happiness directed toward me, toward us, feels contingent on the fact that we’ve jumped through the correct hoops.

In today’s liberal democratic states a substantial portion of law is dedicated to erecting a “just” basis for exclusion, to pretending that the universal right to leave any country exists when it doesn’t. The wealthy, despite their racial identity or country of origin, transcend borders. But here, in the domain of restrictive immigration policy, democracy reaches its vanishing point. Considering the history of colonialism and the continued economic and political force exerted by the global North on the global South, restrictive immigration policy looks like affluent states shielding themselves against the misery they create elsewhere. The more I turn these thoughts over in my mind, the more grating the chorus’s harmonizing becomes. This is pure spectacle, one in which forty-seven people are offered as proof the system is working, that the spirit of democracy exists for everyone, that human dignity is respected, that inalienable rights are recognized, and that liberty is for all who show up to claim it.

A representative for Iowa congressman Dave Loebsack reads a statement.“You are proof that the American dream is alive and well!” he says. Then there is more singing.

The judge tells us we are not yet citizens, that we’ll become citizens the moment we utter the words “I will,” affirming our willingness to take up arms and uphold hollow ideals put on paper by people who bought and sold human beings, while our military’s drones “legally” rain death from above and violate the sovereignty of other nations, some of whose people are being naturalized here today. The judge reads through each person’s country of origin individually: Canada, Eritrea, Latvia, China, Montenegro, Pakistan, Romania, the Central African Republic, Bolivia, Vietnam, China, India, Kosovo, Pakistan, Pakistan, Pakistan, Nigeria, Mexico, Vietnam, The Philippines, Sweden, Somalia, Jamaica, Venezuela, Kenya, Poland, Liberia, Vietnam, Algeria, Canada, Ukraine, Bosnia, Ukraine, South Korea, Bosnia, India, Mexico, Latvia, The Philippines, Mexico, India, Sri Lanka, India, Bosnia, Sri Lanka, Togo, South Korea. I think the young man with the scars on his head is Liberian, and the woman with the bright orange hair to my left is from Latvia. Number 36 to my right is a small man with dark brown skin from India who turns and smiles at me when the judge reads India, and the kid who, earlier was pummeling a handheld videogame in a corner, belongs to a family from Pakistan.

We all raise our right hand. The judge reads his prompt. We each say, “I will.”

The lights grow dim and a video is projected on a screen onstage. Barack Obama, presumably somewhere in the White House, looks just above and beyond us because he’s not looking into the camera but at cue cards or a teleprompter just to the side.

“I am proud to welcome you as a new citizen of the United States of America.”

How strange to be welcomed now, since I’ve lived my life here from before I can remember. My cultural references are decidedly 80s and 90s United States—Urkel, Alex P. Keaton, Tom & Jerry, Biggie—and despite my best efforts I sometimes slip into a Chicago accent, cutting my A’s short. When I did visit Veracruz as a middle-schooler, the kids I played pickup games of soccer with would immediately detect that something about me was off. I had my first kiss in a bathroom in Bucktown in Chicago in grammar school, and I lost my virginity less than a block away in a church parking lot. The first place I remember living was a yellow brick apartment building across the street from Holstein Park on the corner of Shakespeare and Oakley. The super had plaque psoriasis and lived on the ground floor, and I used to think he was related to me somehow because he was always around. My dad saved my life when he tackled me on Palmer walking toward Western—we’d gotten caught between two teenagers shooting at each other. I wrecked the first car my parents ever bought three days after they’d made the last payment, crossing North Avenue on Honore.

I don’t feel any different after saying “I will,” but I know there are some real changes that have just taken place, not to my body—and it’s really too soon for anything to have changed in my mind—but to the relations I have to the place in which I live, its bureaucracy, and its ability to restrict my movement. The virtual me—constructed and siphoned from various sources of data—will be transmitted across their interlinked databases differently, coded differently. The list of potential punishments for my actions has been reconfigured and shrunk. I’ve been allowed to join the club, brought into new spheres of influence and slipped out of others, and all in one breath. It isn’t lost on me that people die in pursuit of this condition I’ve just entered.

The official Customs and Border Protection number of migrants’ lives lost in the Southwest during fiscal year 2010 is 365. This number is almost certainly too low. The number of South and Central American migrants killed in their transit through Mexico on their way here is unknown. Migrant massacres numbering close to one hundred are not uncommon. Falling off the side of La Bestia, a freight train used for transport through Mexico, and never being identified is not uncommon. About 11,000 South and Central American migrants were kidnapped in a six-month period last year. Globally, thousands of people perish making this wager, attempting to make their way to the global North. They die in the Sahara, along the US-Mexico border, in Mexico, in the Mediterranean, in Australian waters, around the Horn of Africa, in the Bay of Bengal, and in the Caribbean. They are the poorest, those who cannot afford to make their way into a country on a tourist visa or on an airplane. Many come from indigenous populations. Most are dark-skinned.

The ceremony in West Branch, Iowa, reaches its nadir when a video is cued up and a twangy guitar or maybe synthesizer begins Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the USA.” A video montage that reminds me of every propaganda film I’ve ever seen begins diffusing cliché images intended, I suppose, to kick-start our patriotism for the new homeland: a snow-capped mountain, a swooping helicopter shot of a golden field of grain, a bald eagle soaring above a forest, a roaring river, a flag undulating in the sky. Usually I would find this comical, but about halfway through I feel a shudder. This song had been playing a lot on the radio lately, and I’ve come to find out that it was originally popular as US-led coalition forces dropped 90,000 tons of bombs during the Gulf War. It became popular again just after Operation Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan) and Operation Iraqi Freedom, and it’s in the middle of a resurgence that started a little over a month ago when Beyoncé premiered her cover on Piers Morgan Tonight, three nights after the assassination of Osama bin Laden. The song reminds me not only of the televised images I’d seen during my childhood of Kuwait on fire, but also of the drunken crowds I recently saw taking to the streets in the small Iowa city in which I live. At first I didn’t know what was happening because I didn’t own a television, and I assumed it had something to do with football, but my neighbor knocked on my door to tell me the news. Crowds of drunken college students and locals spilled out of apartment buildings, frat houses, and bars onto the streets. It looked exactly the same as the white rioting that happens when the football team wins, except in stead of black-and-gold banners they were waving the stars and stripes and chanting “U-S-A! U-S-A! U-S-A!” Rather than celebrating a sporting victory, though, they were in ecstasy over the revenge assassination of Osama bin Laden, which we would later come to learn allegedly happened in front of his twelve or thirteen-year-old daughter.

Without a trace of self-awareness, the old white judge tells us that America is the home of immigrants: “Baryshnikov, the dancer; Einstein, the scientist; Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor; Wayne Gretzky, the hockey player.” I retrieve a handful of papers from inside my large white envelope. The first sheet is a form letter from Obama. I skim it as the judge announces he’ll be taking photographs with people on stage. I glance over, and number 38 is wiping away a tear. “You’re one of us now”—this is the overwhelming sentiment of the letter. A woman who’s just been naturalized takes her whole family up for a photo: several children, a husband, and a baby. The judge holds the baby—his idea. Something falls from the papers I’m holding onto the ground. It’s a government-printed informational pamphlet about applying for a US passport. The front reads, “With Your U.S. Passport, the World is Yours!”

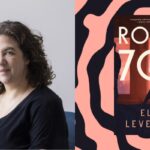

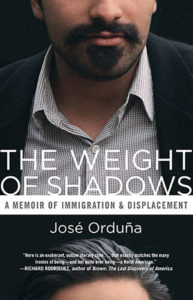

From The Weight of Shadows: A Memoir of Immigration and Displacement. Used with permission of Beacon Press. Copyright 2016 by

José Orduña

José Orduña was born in Córdoba, Veracruz, and immigrated to Chicago when he was two. At nine, he and his parents traveled to Ciudad Juárez and filed for permanent residency under section 245(i) of the Immigration and Nationality Act. Having entered the United States with a tourist visa, which had since expired, they were considered “removable aliens.” In December of 2010, while in graduate school, Orduña applied for naturalization, and in July of 2011 was sworn in as a United States citizen. He is a graduate of the Nonfiction Writing Program at the University of Iowa and is active in Latin American solidarity and advocates for immigrant rights.