On the Great Old White Guy Vocal Fry Panic of 2013

Actually, When We Take Vocal Patterns Seriously, It Tells Us a Lot

It’s 2013, and Bob Garfield is in a state of exasperation. “Vulgar,” he spits into his microphone. “Repulsive.” I’m listening to an episode of the NPR host’s language-themed podcast, Lexicon Valley. Though I cannot see 58-year-old Garfield with my own eyes, from the disdain in his voice, I can picture him, scornfully stroking his frosty-white facial hair and crossing one corduroy-clad arm over the other. The topic of discussion is a linguistic phenomenon that Garfield says is so endlessly “annoying” that he wishes he could “wave a magic wand over a significant portion of the American public and make it come to an end.” It is an oddity that occurs “exclusively” among young women, he tells co-host Mike Vuolo with conviction. “I don’t have any data [proving this],” he says. “I simply know I’m right.”*

Any guesses as to what this odious feminine speech quality could be? It’s vocal fry, also known by linguists as creaky voice. You may have heard of this phenomenon or even do it yourself: vocal fry is a raspy, low-pitched noise that we often hear as people trail off at the ends of their sentences. The sound is produced when a speaker compresses their vocal cords, reducing the air flow and frequency of vibrations through the larynx, causing the voice to sound sort of, well, creaky. Like a rusty door, or the grate of a Mexican guiro. (Commentators like to reference the voices of Valley girls and Kim Kardashian when describing vocal fry—in fact, it is a part of a legitimate dialect colloquially termed “Valley girl speak”— though people of all genders and geographical locations do it too.)

Garfield says that in recent years, he’s noticed a vocal fry epidemic in the speech of women in their teens and twenties—nothing but a “mindless affectation”—and he is certain that it’s irreparably ruining the English language. To demonstrate the sound, Garfield beckons his eleven-year-old daughter to the microphone. “Ida, be obnoxious,” he instructs.

In the years following this podcast, vocal fry becomes increasingly mauled and mocked by the media—a public emblem of young women’s overall inability to communicate as elegantly as older, wiser men. In 2014 the Atlantic publishes a report that women who talk with vocal fry are less likely to be hired. In 2015 a male Vice reporter publishes a story called “My Girlfriend Went to a Speech Therapist to Cure Her Vocal Fry.” The same year, journalist Naomi Wolf pens an article for the Guardian titled, “Young women, give up the vocal fry and reclaim your strong female voice.” She writes, “‘Vocal fry’ is that guttural growl at the back of the throat, as a Valley girl might sound if she had been shouting herself hoarse at a rave all night.”

I myself remember being berated for using vocal fry in high school by a male theater teacher who told me that if I continued contaminating my lines with creak, I would never make it to Broadway. (Could this be the reason I was not cast as one of the original stars of Hamilton?)

Of course vocal fry isn’t the only thing wrong with young female voices. Around the same time of Bob Garfield’s episode, the internet has a collective freakout over contemporary “lady language,” and journalists everywhere start cranking out think pieces analyzing other characteristics commonly noticed and reviled in women’s speech. Saying like after every other word is a well-known example. So is apologizing too much; using hyperbolic internet slang (“OMG, I AM LITERALLY DYING”); and speaking with uptalk, where you end a declarative sentence with the upward intonation of a question.

Vocal fry, uptalk, and even like, are in fact not signs of ditziness, but instead all have a unique history and specific social utility.

Suddenly, making poorly informed, pseudofeminist claims about how women talk becomes the trendy thing for brands and magazines to do. In 2014 hair care company Pantene releases an advertisement encouraging women to stop saying “sorry” all the time. (Because now not only does your hair need a makeover, so does your speech!) A year later, publications like Time and Business Insider begin claiming that uptalk makes women sound timid and self-conscious. YOUNG LADY, IF YOU EVER WANT A JOB OR A HUSBAND YOU MUST STOP TALKING THIS WAY, the internet screams.

At the height of this media frenzy, I was a twenty-something woman, the very target of these articles and commercials, and I had three concerns: 1) whether or not speech qualities like vocal fry and uptalk are really exclusive to young women; 2) the purpose they serve, if so; and 3) why everybody hates them so much.

Fortunately, there are plenty of language experts who’ve taken “Valley girl” speak seriously enough to figure out what it actually is. One of these scholars is Carmen Fought, a linguist from Pitzer College (who, incidentally, has one of the butteriest, most soothing speaking voices I’ve ever heard). As Fought says, “If women do something like uptalk or vocal fry, it’s immediately interpreted as insecure, emotional, or even stupid.” But the truth is much more interesting: Young women use the linguistic features that they do, not as mindless affectations, but as power tools for establishing and strengthening relationships. Vocal fry, uptalk, and even like, are in fact not signs of ditziness, but instead all have a unique history and specific social utility. And women are not the only people who use them.

In many languages around the world, vocal fry is not some random quirk—it is built into their very phonology. For instance, in Kwak’wala, a Native American language, the word for day cannot be pronounced without using creak, or else it wouldn’t make sense (kind of like pronouncing the English word day without the y). What’s interesting about English speakers’ use of vocal fry is that early studies actually attributed the speech quality primarily to men. One of the first official observations of vocal fry in English was made by a UK linguist in the 1960s, who determined that it was British dudes who employed vocal fry as a way of communicating a higher social standing. There was also an American study of creaky voice in the 1980s that called the phenomenon “hyper-masculine” and a “robust marker of male speech.” Many linguists also agree that using a bit of creak at the ends of sentences has been happening in the United States among English speakers of all genders, with no fuss or fallout, for decades.

But in the mid-2000s, folks started noticing an increase of vocal fry usage in the voices of American college-age women, but not so much in their male classmates. Researchers were intrigued, so they decided to take a gander and see if these observations were accurate. Long story short, they were: in 2010, linguistics scholar Ikuko Patricia Yuasa published a study showing that American women use vocal fry about 7 percent more than American men. And we’ve been getting creakier ever since.

But, like, why? What is vocal fry good for? (Other than to annoy beardy old guys, that is.) As it turns out, a bunch of things. First, Yuasa points out that since vocal fry is so very low in pitch, it could be a way for women to compete with men’s voices—to sound more authoritative. “Creaky voice may provide a growing number of American women with a way to project an image of accomplishment, while retaining female desirability,” she wrote in her study. Personally, I have found myself unconsciously dropping into vocal fry during presentations at work to convey this sort of laid-back authority. “You always sound like you know what you’re talking about to me,” said my boss when I asked her if I ever came off as insecure during meetings. (Then again, she’s a woman in her twenties too.)

On the flip side, Mark Liberman, a linguist at the University of Pennsylvania, told the New York Times in 2012 that vocal fry can also be used to convey a sense of disinterest in a topic (which, as a teenage girl, I certainly loved to do). “It’s a mode of vibration that happens when the vocal cords are relatively lax. . . . So maybe some people use it when they’re relaxed and even bored,” he said. Like a subtle way of telling someone you find them unstimulating.

To sum things up, over the first two decades of the 21st century, women began speaking with increasingly lower-pitched voices, attempting to convey more dominance and expressing more boredom—all things that middle-aged men have historically not been in favor of women doing. Perhaps this could explain why Bob Garfield and his peers have scrutinized vocal fry so mercilessly?

__________________________________

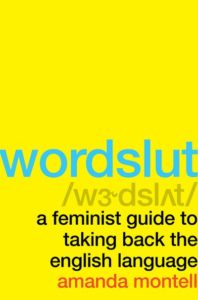

From Wordslut by Amanda Montell. Copyright © 2019 by Amanda Montell. Published on May 28, 2019 by Harper Wave, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Amanda Montell

Amanda Montell is a writer and linguist from Baltimore. She is the author of the acclaimed books Wordslut, Cultish, and The Age of Magical Overthinking. Along with hosting the podcast Sounds Like a Cult, her writing has also appeared in The New York Times, Marie Claire, Cosmopolitan, and more. She holds a degree in linguistics from NYU and lives in Los Angeles with her partner, plants, and pets. Find her on Instagram @Amanda_Montell.