On the Glorious Queerness of Metrical Narrative

Cat Fitzpatrick’s Celebration of “Absurd Embellishments”

There’s a passage in Gertrude Stein about how hard it is to want things other people don’t take seriously:

It is very hard to know what you are liking, whether you are not really liking something that is a low thing to yourself then, it is a very difficult thing to get the courage to buy the kind of clock or handkerchiefs you are loving when every one thinks it is a silly thing, when every one thinks you are doing it for the joke of the thing. It takes very much courage to do anything connected with your being that is not a serious thing.

Stein is talking about aesthetics (clocks, handkerchiefs, modernism) but also about being gay, or maybe trans. When I read this passage, I thought, I know the feeling. When I came out in 2001, I didn’t know anyone else who was trans (or who even knew anyone else who was trans). Being trans wasn’t yet serious and controversial and even a bit cool; it was just weird. No one else took it seriously, but, embarrassingly, I had to do it anyway.

In much the same way, I have spent a lifetime, since I was about 12 or 13, teaching myself to write metrical rhyming verse, essentially from books, by copying, without knowing anyone else who was doing this. No one around me took this endeavor seriously, and yet it was, I knew, connected with my being. Not they they’re not out there, the metrical versifiers—of course they are. The transsexuals were, too. But still, this has been an embarrassing thing to love.

Modernism, Modernists (like Stein) elevated the doing-away-with of things to a heroic virtue. Curlicues, harmony, figuration, verse, whatever it was: we would move forward into a glorious future without these absurd embellishments into a purer, cleaner future.

Verse novels are gay, in the pejorative (i.e. desirable) sense: heightened, effortful and beautiful.

Except for me. I love absurd embellishments, and I am stuck in the past. All my favorite novels are verse novels: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Troilus and Criseyde, Paradise Lost, Don Juan, Aurora Leigh, Amours de Voyage, The Golden Gate. I have even endeavored to write one myself.

There is a passage in Black trans Scottish writer Shola Von Reinhold’s magnificent novel Lote about how, just because something is now of no use to other people, it doesn’t mean it is of no use to you. It describes a (fictional) Black figurative oil painter, Anton Amo. Responding to a critic who has pronounced his choice of form inherently obsolete and “unable to generate anything really worthwhile,” Amo writes an essay entitled White People Shouldn’t Paint (or Write Novels, or Study Ancient Greek):

The premise of his article had been that countless white art critics and artists in the west have pronounced the death of painting […] Such pronouncements, made after the luxury of several centuries unhampered access to the form, willfully ignore the fact that many have simply not had this access. Until the Black diaspora, amongst various other groups, has come close to that length of commodious interaction with the form […] then perhaps these pronouncements should be rephrased from “painting is dead”, to “white people shouldn’t paint” […] The article admitted in the final paragraph to hoping to aggravate, to challenge assertions. It was clear it was not really a true call for the end of white people making art. The argument could be reapplied to fiction, literary studies, classical studies, and so on. Indeed, anything that had been claimed dead before others had been able to glut themselves upon it, and in doing so, provide new insights.

Von Reinhold is making her argument through the specificities of the historical suppression of Black art and artists, but she is also, as she makes clear in the last sentences here, making a point with broad application to “various other groups.” The secret society of worshippers of luxury and ornament she invents, the Lote-Os, includes everyone from black working-class queers to white heiresses.

As a white heiress of sorts, as I read Lote, I felt deep sense of excitement and gratitude for its argument. Verse narratives are a form often pronounced old, dead, and outdated, and yet, in the long history of verse narrative in English, representations of what we are now calling transness are minimal. Perhaps (though I am skeptical) some number of straight white writers, or even cis queer white writers, might feel that all they could possibly say or do with meter and rhyme has been done, but I still have business with it.

I am, of course, far from the only person to still have such business. Hip-hop, after all, represents nothing less than the construction, over the last 50 or so years, of a whole new astonishing and massively popular metrical tradition from the ground up, because people still have business with meter. Perhaps, over the next centuries, a variety of hip-hop meter, or something else, will completely replace the meter I use. Perhaps, like the Gawain poet—who wrote in alliterative meter as it was going out of fashion for good, to be replaced by the kind of meter I write—I am actually at the end of a tradition.

If so, I want there to be some trans stories written in my meter before it ends. Still, I hope I am not at the end of it because (and this is the key point) that old meter is still so good.

*

Meter is nothing more than a set of techniques for exploiting certain linguistic resources. It allows you to include a lot of information about how words would sound aloud, even as you only actually write symbols on a page.

Here is a passage from Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh:

She said sometimes “Aurora, have you done

Your task this morning? Have you read that book?

And are you ready for the crochet here?”

As if she said, “I know there’s something wrong;

I know I have not ground you down enough

To flatten and bake you to a wholesome crust

For household uses and proprieties,

Before the rain has got into my barn

And set the grains a-sprouting. What, you’re green

With out-door impudence? You almost grow?”

To which I answered, “Would she hear my task,

And verify my abstract of the book?

Or should I sit down to the crochet work?

Was such her pleasure?” Then I sate and teased

The patient needle till it split the thread,

Which oozed off from it in meandering lace

From hour to hour. I was not, therefore, sad;

My soul was singing at a work apart.

Barrett Browning is writing, more or less, in iambic pentameter. It goes de DUM de DUM. Listen:

For HOUSE-hold US-es AND pro-PRI-e-TIES

Aurora Leigh, the narrator of the story, is also its main character. She makes mistakes and misunderstands things, but she is essentially someone we root for, love, admire, and take seriously. Aurora is serious, and so, up to a point, is her meter.

Iambic meter puts the unstresses first, and maintains only one unstress between stresses. It’s easier to start a paragraph or phrase in English on an unstress. If a phrase starts on an article (the, a) or a pronoun (he, she, they, it) or a conjunction (and, but) or even with a word with a prefix, it’s probably an unstress. Iambic meter also places one unstress between every stress. In spoken English we more frequently have one unstress between stresses than two or three. Because of these two features, Iambic is the most natural and flexible fixed meter in English—much easier to use than ones that start with a stress (e.g. trochaic) or insist on two unstresses between stresses (e.g. anapestic) or both (e.g. dactylic).

Nevertheless, it is quite different from normal speech, where sometimes we have two or three unstresses between stresses, and sometimes none. To maintain the rhythm of iambic pentameter, syllables that might normally be unstressed have to be made stressed; meanwhile, prepositions and pronouns and conjunctions and prefixes and suffixes that might be skipped over have to be emphasized.

Look, to give a minor, but for that reason telling, example, at the unusually intense stresses the meter produces on the “and” and on the last syllable of “proprieties” in the line I’ve scanned above. Look how much extra sarcasm and bitterness this stressing gives the line. As compared to prose, it turns up the volume, makes everything just a little more. And over a whole book, this kind of small skillful increase of semantic and emotional density adds up to a lot. This excess is the joy of the verse novel. It’s also probably why the modernists and their successors disapproved of even serious verse narratives like this.

And of course, no one says verse narratives have to be serious.

My favorite verse novel to have been written in my lifetime is Vikram Seth’s 1986 The Golden Gate. Seth is famous for his prose novels, but I think The Golden Gate is hands down his best book, and it’s certainly his gayest:

He thinks of Paul. He thinks. . . John hails him

Across the clouds of smoke-filled air,

Wrestles his way through, and assails him

With “Now that we’ve achieved this rare

Moment to talk, we’d better use it!

Here’s a straight question- don’t refuse it

Why have you left your job?” “To save

The world,” replies Phil with a grave

Decorum. “Ah,” says John. “Fantastic!

Guess we young yuppies all should go

Do our own thing.” Phil murmurs, “Oh

Young yuppies – now – that’s pleonastic . . .”

“Touché,” says John; then, “Phil, you’re mad.

What better job could you have had?”

The form here is one developed in Russian by Alexander Pushkin for his novel Evgeny Onegin, now known as the Onegin Stanza. It is mostly iambic, but with four, not five, beats per line, and nearly half the rhymes, which come in a complex pattern, are required to be double-syllable rhymes. Apparently all this it is easier to handle in Russian, but in English it is not easy at all.

As a result, Seth’s Onegin Stanza, by contrast with Barrett Browning’s subtle unrhymed iambics, is obviously unnatural, showy, excessive, absurd… in a word, camp. I mean, he rhymes “fantastic” (said bitchily, of course) with “pleonastic”! Barrett Browning’s verse is more; Seth’s verse is too much.

To be too much is widely considered embarrassing. It seems like trying. And indeed, it’s not easy to write a verse novel and pretend you aren’t trying (arguably, Byron managed it in Don Juan by deliberately writing bad verse). Verse novels can be fun and fleet, but they are also necessarily dense, and ornamental, and aesthetic.

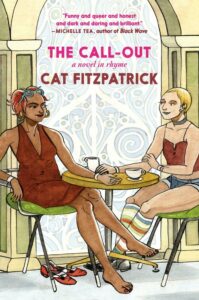

That’s why, when I started to write a novel about the trans community I see around me in Brooklyn, I knew it had to be in Onegin Stanzas. The Call-Out is a gluttonous book, feasting to excess on trans life, cramming as many picnics and drag shows and club nights and literary readings as possible into its frame of plot. It is only fitting that it should feast also on the extra possibilities, both subtle and flagrant, that verse allows.

The prevailing opinion has been, for over a century, that verse novels, especially rhyming ones, are something which is not at all a serious thing. And I will admit, they do often, even at their most serious, teeter on the ludicrous. That’s what’s so good about them! Verse novels are gay, in the pejorative (i.e. desirable) sense: heightened, effortful and beautiful. They offer an opportunity to reclaim the baroque, passionate, and densely detailed. I want that. And I think, as Shola von Reinhold so eloquently argues, that I, and indeed we—all of us various groups of others—should demand it. Verse narrative now!

__________________________________

The Call-Out: A Novel in Rhyme by Cat Fitzpatrick is available via Seven Stories Press.

Cat Fitzpatrick

CAT FITZPATRICK is the first trans woman to serve as Director of the Women’s and Gender Studies program at Rutgers University–Newark, and the Editrix at LittlePuss Press. She is the author of a collection of poems, Glamourpuss (Topside Press) and co-edited the anthology Meanwhile, Elsewhere: Science Fiction & Fantasy from Transgender Writers, which won the ALA Stonewall Award for Literature. The Call-Out is her first novel.