On the Fever Dream Brilliance of Harry Crews

Kevin Wilson Considers What It Means to Be a Southern Writer

I was initially drawn to Harry Crews because he had a mohawk and a tattoo of a skull, and I was twenty years old and had neither. I read Harry Crews because I wanted to figure out how, if you were a Southern writer, you didn’t simply cover the same terrain that writers like Faulkner and Welty and O’Connor and McCullers had already exhausted. I wanted to know how you leaned into what it meant to be Southern when you weren’t even sure what that meant, exactly. And I came away from Harry Crews knowing, on some level, that I wouldn’t ever write like him, could never open the wounds with the kind of ferocity that came only from knowing you’d survive it, because you’d survived much worse. And I remain a fan of Harry Crews because I still don’t know that I’ve read anyone quite like him.

My friend, the California writer Rufi Thorpe, wrote a brilliant novel called The Knockout Queen, and I emailed her to say how much I loved it. I mistakenly called it The Knockout Artist, the title of one of Crews’s novels, and she instantly wrote back to ask if I knew of Crews and his work. She told me, “I feel like the thing about Harry Crews is that someone is supposed to give you, like, a used, crumbly paperback copy, and you read it and go: I didn’t know you were allowed to write a book like that.”

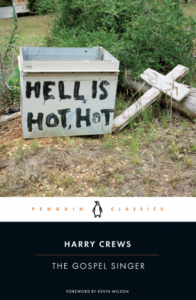

I found a crumbly paperback copy of A Feast of Snakes in the lounge of the English Department offices at Vanderbilt University when I was an undergraduate there. I read The Knockout Artist and The Gospel Singer in rapid succession, and what I realized was, yes, I did not know you could write books like these.

My mentor at the University of Florida, where I received my MFA and where Harry Crews once taught, was Padgett Powell, and he spoke often of the dangers of lazy Southern writing, of creating what he termed “unmitigated pone.” I had never been a Southern-by-the-grace-of-god writer, but I also knew how easy it was to lean on the stereotypes of the Deep South, the alternating nobility and savagery of rural life. And yet, if you look at Crews’s first novel, The Gospel Singer, you have a traveling freak show, pigs allowed to roam the interior rooms of the family home, any number of broken country people with oversized heads and missing legs. You have the violence and Christ-hauntedness and freakishness. How does Crews keep this from becoming “unmitigated pone”?

Crews grapples with race and gender and religion and place, but he stretches them to the breaking point.

In The Gospel Singer, he pushes so hard on the absurdity that the corn isn’t baked, but rather turns into a mash, slightly poisonous, a fever dream. The Gospel Singer, a man possessing a beautiful voice and rum red to have the power to heal the sick, is a sex addict, who, when asked by his mother if he even likes to sing, replies, “Sometimes I do.” The Freak Fair that is following the Gospel Singer from town to town is run by a man named Foot. He has a twenty-seven-inch-long foot. Not feet. Foot. He is, quite possibly, the sanest and most self-possessed character in the novel. If Flannery O’Connor, a fellow Georgia writer and obvious touchstone for Crews’s work, has the Church of Christ Without Christ, Crews invents the Church of the Gospel Singer.

The novel opens in a jail cell, where Willalee Bookatee Hull, an African American man and the preacher who serves the church, is being held for the rape and murder of the Gospel Singer’s supposed betrothed, Mary-Bell Carter, who has been stabbed sixty-one times with an ice pick. The town itself, which awaits the return of the Gospel Singer in order to save them from their own tragedy, is named Enigma. It is, Crews tells us in the very first line of the novel, “a dead end.”

It’s a song, in a voice you’ve never heard, and it’s calling you to come closer, toward your reckoning.

But the chaos, the absurdity, the “mitigated pone,” means nothing without Crews’s writing, sentences that seem both jagged and precise, so clear that you can’t help but see things that you would prefer not to. Early in the novel, the Gospel Singer’s brother, Gerd, remembers their Cousin Maze, dead from a mule’s kick to the head, his wound “about as long and as deep as a briar scratch on his neck at the hairline and a spot of blood no bigger than the end of a man’s thumb blossoming out of his pale skin, but the back of his head was soft—like a balloon filled with jello.”

In this chaotic and violent novel, Crews grapples with race and gender and religion and place, but he stretches them to the breaking point, until the crowd that has amassed in order to be saved by the Gospel Singer are whipped into such a frenzy, constantly edging closer and closer to the h art of the story, that you cannot help but be swallowed up by them. If you survive, it is pure chance, and there will be a scar to remind you.

The Gospel Singer’s agent, Didymus, states that “suffering was God’s greatest gift to man,” and if this is true, and The Gospel Singer makes a convincing case in its favor, then Crews accepts this gift without hesitation. There are freaks, but they are not meant to be aberrations, not deviations from the order of the world. They are the physical embodiment of our shared existence, and if the Gospel Singer’s fate is tied to that of Willalee Bookatee Hull at the end of the novel, Crews offers the flawed idea that “if evil set into motion a chain of events that caused an eventual good, larger than the original evil, then it ceased to be evil.” The problem is the uncertainty of how long that chain of events will last. How much suffering and pain must be endured in the name of that original act of evil? Will we ever find that eventual good? Or does the evil act merely give birth to a new one, and the cycle continues, burying the past in the hopes that we can escape it? All Didymus can do when one of the family’s dogs seeks to attack him, to “do an evil,” is to reply, “You don’t get me tonight!”

At the end of the novel, after all the violence and the shock at that violence, a reporter, Richard Hognut, sent to cover the Gospel Singer’s performance in Enigma, notes that his audience would not have “expected him to solve anything. But they expected him to put it into some kind of context. And he did not even know how to begin talking about what had happened here.” But Crews, somehow, does. While Hognut says, “To hell with the story! Let somebody else get it,” you realize that Crews is right there, those brilliant detonations of language, that clear-eyed view into what makes us monstrous and human. It’s a song, in a voice you’ve never heard, and it’s calling you to come closer, toward your reckoning.

__________________________________

From The Gospel Singer by Harry Crews, published by Penguin Classics, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Foreword Copyright © 2022 by Kevin Wilson.

Kevin Wilson

Kevin Wilson is the author of two collections, Tunneling to the Center of the Earth (Ecco/Harper Perennial, 2009), which received an Alex Award from the American Library Association and the Shirley Jackson Award, and Baby You’re Gonna Be Mine (Ecco, 2018), and three novels, The Family Fang (Ecco, 2011), Perfect Little World (Ecco, 2017) and Nothing to See Here (Ecco, 2019), a New York Times bestseller and a Read with Jenna book club selection. His fiction has appeared in Ploughshares, Southern Review, One Story, A Public Space, and elsewhere, and has appeared in Best American Short Stories 2020 and 2021, as well as The PEN/O. Henry Prize Stories 2012. He has received fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, Yaddo, and the KHN Center for the Arts. He lives in Sewanee, Tennessee, with his wife, the poet Leigh Anne Couch, and his sons, Griff and Patch, where he is an Associate Professor in the English Department at Sewanee: The University of the South.