On the Eerie, Enduring Power of the Rorschach Test

How a 100-Year-Old Test Still Reveals More Than We Think

Victor Norris had reached the final round of applying for a job working with young children, but, this being America at the turn of the 21st century, he still had to undergo a psychological evaluation. Over two long November afternoons, he spent eight hours at the office of Caroline Hill, an assessment psychologist working in Chicago.

Norris had seemed an ideal candidate in interviews, charming and friendly with a suitable résumé and unimpeachable references. Hill liked him. His scores were normal to high on the cognitive tests she gave him, including an IQ well above average. On the most common personality test in America, a series of 567 yes-or-no questions called the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, or MMPI, he was cooperative and in good spirits. Those results, too, came back normal.

When Hill showed him a series of pictures with no captions and asked him to tell her a story about what was happening in each one—another standard assessment called the Thematic Apperception Test, or TAT—Norris gave answers that were a bit obvious, but harmless enough. The stories were pleasant, with no inappropriate ideas, and he had no anxiety or other signs of discomfort in the telling.

As early Chicago darkness set in at the end of the second afternoon, Hill asked Norris to move from the desk to a low chair near the couch in her office. She pulled her chair in front of his, took out a yellow legal pad and a thick folder, and handed him, one by one, a series of ten cardboard cards from the folder, each with a symmetrical blot on it. As she handed him each card, she said: “What might this be?” or “What do you see?”

Five of the cards were in black and white, two had red shapes as well, and three were multicolored. For this test, Norris was asked not to tell a story, not to describe what he felt, but simply to say what he saw. No time limit, no instructions about how many responses he should give. Hill stayed out of the picture as much as possible, letting Norris reveal not just what he saw in the inkblots but how he approached the task. He was free to pick up each card, turn it around, hold it at arm’s length or up close. Any questions he asked were deflected:

Can I turn it around?

It’s up to you.

Should I try to use all of it?

Whatever you like. Different people see different things.

Is that the right answer?

There are all sorts of answers.

After he had responded to all ten cards, Hill went back for a second pass: “Now I’m going to read back what you said, and I want you to show me where you saw it.”

Norris’s answers were shocking: elaborate, violent sexual scenes with children; parts of the inkblots seen as female being punished or destroyed. Hill politely sent him on his way—he left her office with a firm handshake and a smile, looking her straight in the eye—then she turned to the legal pad facedown on her desk, with the record of his responses. She systematically assigned Norris’s responses the various codes of the standard method and categorized his answers as typical or unusual using the long lists in the manual. She then calculated the formulas that would turn all those scores into psychological judgments: dominant personality style, Egocentricity Index, Flexibility of Thinking Index, the Suicide Constellation. As Hill expected, her calculations showed Norris’s scores to be as extreme as his answers.

If nothing else, the Rorschach test had prompted Norris to show a side of himself he didn’t otherwise let show. He was perfectly aware that he was undergoing an evaluation, for a job he wanted. He knew how he wanted to come across in interviews and what kind of bland answers to give on the other tests. On the Rorschach, his persona broke down. Even more revealing than the specific things he had seen in the inkblots was the fact that he had felt free to say them.

This was why Hill used the Rorschach. It’s a strange and open-ended task, where it is not at all clear what the inkblots are supposed to be or how you’re expected to respond to them. Crucially, it’s a visual task, so it gets around your defenses and conscious strategies of self-presentation. You can manage what you want to say but you can’t manage what you want to see. Victor Norris couldn’t even manage what he wanted to say about what he’d seen. In that he was typical. Hill had learned a rule of thumb in grad school that she had repeatedly seen confirmed in practice: a troubled personality can often keep it together on an IQ test and an MMPI, do pretty well on a TAT, then fall apart when faced with the inkblots. When someone is faking health or sickness, or intentionally or unintentionally suppressing other sides of their personality, the Rorschach might be the only assessment to raise a red flag.

“You can manage what you want to say but you can’t manage what you want to see.”

Hill didn’t put in her report that Norris was a past or future child molester—no psychological test has the power to determine that. She did conclude that Norris’s “hold on reality was extremely vulnerable.” She couldn’t recommend him for a job working with children and advised the employers not to hire him. They didn’t.

Norris’s disturbing results and the contrast between his charming surface and hidden dark side stayed with Hill. Eleven years after giving that test, she got a phone call from a therapist who was working with a patient named Victor Norris and had a few questions he wanted to ask her. He didn’t have to say the patient’s name twice. Hill was not at liberty to share the details of Norris’s results, but she laid out the main findings. The therapist gasped. “You got that from a Rorschach test? It took me two years of sessions to get to that stuff! I thought the Rorschach was tea leaves!”

Despite decades of controversy, the Rorschach test today is admissible in court, reimbursed by medical insurance companies, and administered around the world in job evaluations, custody battles, and psychiatric clinics. To the test’s supporters, these ten inkblots are a marvelously sensitive and accurate tool for showing how the mind works and detecting a range of mental conditions, including latent problems that other tests or direct observation can’t reveal. To the test’s critics, both within and outside the psychology community, its continued use is a scandal, an embarrassing vestige of pseudoscience that should have been written off years ago along with truth serum and primal-scream therapy. In their view, the test’s amazing power is its ability to brainwash otherwise sensible people into believing in it.

Partly because of this lack of professional consensus, and more because of a suspicion of psychological testing in general, the public tends to be skeptical about the Rorschach. The father in a recent well-publicized “shaken baby” case, who was eventually found innocent in the death of his infant son, thought the assessments he was subjected to were “perverse” and particularly “resented” being given the Rorschach. “I was looking at pictures, abstract art, and telling them what I was seeing. Do I see a butterfly here? Does that mean I’m aggressive and abusive? It’s insane.” He insisted that while he “put stock in science,” which he called an “essentially male” worldview, the social services agency evaluating him had an “essentially female” worldview that “privileged relationships and feelings.” The Rorschach test is in fact neither essentially female nor an exercise in art interpretation, but such attitudes are typical. It doesn’t yield a cut-and-dried number like an IQ test or a blood test. But then nothing that tries to grasp the human mind could.

The Rorschach’s holistic ambitions are one reason why it is so well known beyond the doctor’s office or courtroom. Social Security is a Rorschach test, according to Bloomberg, as is the year’s Georgia Bulldogs football schedule (Sports Blog Nation) and Spanish bond yields: “a sort of financial-market Rorschach test, in which analysts see whatever is on their own minds at the time” (Wall Street Journal). The latest Supreme Court decision, the latest shooting, the latest celebrity wardrobe malfunction. “The controversial impeachment of Paraguay’s president, Fernando Lugo, is quickly turning into a kind of Rorschach test of Latin American politics,” in which “the reactions to it say more than the event does itself,” says a New York Times blog. One movie reviewer impatient with art-house pretension called Sexual Chronicles of a French Family a Rorschach test that he’d failed.

This last joke trades on the essence of the Rorschach in the popular imagination: It’s the test you can’t fail. There are no right or wrong answers. You can see whatever you want. This is what has made the test perfect shorthand, since the 1960s, for a culture suspicious of authority, committed to respecting all opinions. Why should a news outlet say whether an impeachment or a budget proposal is good or bad, and risk alienating half of its readers or viewers? Just call it a Rorschach test.

The underlying message is always the same: You are entitled to your own take, irrespective of the truth; your reaction is what matters, whether expressed in a like, a poll, or a purchase. This metaphor for freedom of interpretation coexists in a kind of alternate universe from the literal test given to actual patients, defendants, and job applicants by actual psychologists. In those situations, there are very real right and wrong answers.

The Rorschach is a useful metaphor, but the inkblots also just look good. They’re in style for reasons having nothing to do with psychology or journalism—maybe it’s the 60-year fashion cycle since the last burst of Rorschach fever in the 1950s, maybe it’s a fondness for forceful black-and-white color schemes that look good with midcentury modern furniture. A few years ago, Bergdorf Goodman filled its Fifth Avenue windows with Rorschach displays. Rorschach-style T-shirts were recently on sale at Saks, only $98. “My strategy,” proclaimed a full-page splash in InStyle: “This season I’m finding myself very attracted to clothes and accessories that have a sense of symmetry. my inspiration: The patterns of Rorschach inkblots are spellbinding.” The horror-thriller Hemlock Grove, the science fiction cloning thriller Orphan Black, and a Harlem-based tattoo-shop reality show called Black Ink Crew debuted on TV with Rorschachy credit sequences. The video for Rolling Stone’s #1 Best Song of the 2000s and the first single ever to hit the top of the charts from internet sales, Gnarls Barkley’s “Crazy,” was a mesmerizing animation of morphing black-and-white blots. Rorschach mugs and plates, aprons and party games are available everywhere.

Most of these are imitation inkblots, but the ten originals, now approaching their hundredth birthday, endure. They have what Hermann Rorschach called the “spatial rhythm” necessary to give the images a “pictorial quality.” Created in the birthplace of modern abstract art, their precursors go back to the 19th-century brew that gave rise to both modern psychology and abstraction, and their influence reaches across 20th- and 21st-century art and design.

In other words: three different histories spill together into the story of the Rorschach test.

“For many years, the test was hyped as an X-ray of the soul. It’s not, and it wasn’t originally meant to be, but it is a uniquely revealing window on the ways we understand our world.”

First, there is the rise, fall, and reinvention of psychological testing, with all its uses and abuses. Experts in anthropology, education, business, law, and the military have also long tried to gain access to the mysteries of unknown minds. The Rorschach is not the only personality test, but for decades it was the ultimate one: as defining of the profession as the stethoscope was for general medicine. Throughout its history, how psychologists use the Rorschach has been emblematic of what we, as a society, expect psychology to do.

Then there is art and design, from Surrealist paintings to “Crazy” to Jay-Z, who put a gold Andy Warhol blot painting called Rorschach on the cover of his memoir. This visual history seems unrelated to medical diagnosis—there’s not much psychology in those Saks shirts—but the iconic look is inseparable from the real test. The agency that pitched a Rorschach-themed video for “Crazy” got the job because singer CeeLo Green remembered having been given the test as a troubled child. Controversy gathers around the Rorschach because of its prominence. It’s impossible to draw a hard and fast line between the psychological assessment and the inkblots’ place in the culture.

Finally, there is the cultural history that has led to all those metaphorical “Rorschach tests” in the news: the rise of an individualistic culture of personality in the early 20th century; widespread suspicion of authority beginning in the 60s; intractable polarization today, with even facts seeming to depend on the eye of the beholder. From the Nuremberg Trials to the jungles of Vietnam, from Hollywood to Google, from the community-centered social fabric of 19th-century life to the longing for connection in the socially fragmented 21st, Rorschach’s ten blots have run alongside, or anticipated, much of our history. When yet another journalist calls something a Rorschach test, it may be just a handy cliché, the same way it is perfectly natural for artists and designers to turn to striking, symmetrical patterns of black on white. No single instance of the Rorschach in everyday life requires any explanation. But its lasting presence in our collective imagination does.

For many years, the test was hyped as an X-ray of the soul. It’s not, and it wasn’t originally meant to be, but it is a uniquely revealing window on the ways we understand our world.

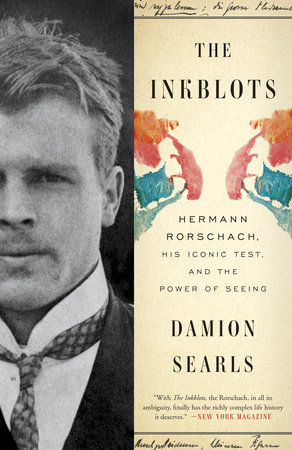

All of these strands—psychology, art, and cultural history—lead back to the creator of the inkblots. “The method and the personality of its creator are inextricably interwoven,” as the editor wrote in the preface to Psychodiagnostics, the 1921 book that introduced the inkblots to the world. It was a young Swiss psychiatrist and amateur artist, tinkering with a children’s game, working alone, who managed to create not only an enormously influential psychological test but a visual and cultural touchstone.

Hermann Rorschach, born in 1884, was “a tall, lean, blond man, swift of motion, gestures, and speech, with an expressive and vivid physiognomy.” If you think he looks like Brad Pitt, maybe with a little Robert Redford thrown in, you are not the first. His patients tended to fall for him too. He was openhearted and sympathetic, talented but modest, sturdy and handsome in his white doctor’s robe, his short life filled with tragedy, passion, and discovery.

Modernity was erupting around him, from the Europe of World War I and the Russian Revolution and from within the mind itself. In Switzerland alone, during Rorschach’s career there, Albert Einstein invented modern physics and Vladimir Lenin invented modern communism while working with the labor organizers in Swiss watch factories. Lenin’s next-door neighbors in Zurich, the Dadaists, invented modern art, Le Corbusier modern architecture, Rudolf von Laban modern dance. Rainer Maria Rilke finished his Duino Elegies, Rudolf Steiner created Waldorf schools, an artist named Johannes Itten invented seasonal colors (“Are you a spring or a winter?”). In psychiatry, Carl Jung and his colleagues created the modern psychological test. Jung’s and Sigmund Freud’s explorations of the unconscious mind were battling for dominance, both among a wealthy neurotic clientele and in the real world of Swiss hospitals filled far past capacity.

These revolutions crossed paths in Hermann Rorschach’s life and career, but despite tens of thousands of studies of the test, no full-length biography of Rorschach has ever been written. A historian of psychiatry named Henri Ellenberger published a sketchily sourced 40-page biographical article in 1954, and that has been the basis for nearly every account of Rorschach since: as pioneering genius, bumbling dilettante, megalomaniac visionary, responsible scientist, and just about everything in between. Speculation has swirled around Rorschach’s life for decades. People could see in it whatever they wanted to see.

The true story deserves to be told, not least because it helps to explain the test’s enduring relevance despite the controversies that have surrounded it. Rorschach predicted most of the controversies himself.

__________________________________

From The Inkblots, by Damion Searls, courtesy Crown. Copyright 2018 by Damion Searls.

Damion Searls

Damion Searls studied philosophy at Harvard and is a prominent translator from German, Norwegian, French, and Dutch, including of books by Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, Rilke, Proust, Victoria Kielland, Saša Stanišić, Jelinek, Mann, Modiano, and Jon Fosse. His own writing includes fiction, poetry, and a widely translated biography of the creator of the Rorschach test.