On the Early Women Pioneers of Trail Hiking

Gwenyth Loose on the Women Who Defied All Expectations

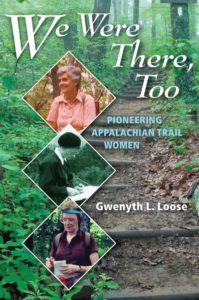

Featured image: Hikers in the White Mountains, courtesy Ginny Folsom Umiker.

Underneath an absurdly large, flouncy hat, her eyelids fluttered and finally closed as Henriette d’Angeville nestled further into the white snows of France’s Mont Blanc. Layers of heavy skirts and a fur cloak—most unsuitable for mountain climbing—wrapped around Henriette as she curled herself comfortably into the mountain’s formidable slope. All too aware of the dangers of allowing sleep to overcome climbers at elevations above fifteen thousand feet, her male guides watched Henriette appear ever-more oblivious to the frighteningly cold and thin air. None of them had ever taken a lady up Mont Blanc, and, despite her present state, they knew Henriette to be courageous and determined. But, how to wake her? How to make her aware of the dangers they all faced if she did not regain her feet and move forward toward the summit?

“We must wake her!” one guide exclaimed.

“Perhaps she is already dead,” another offered.

“Impossible!” Joseph-Marie Couttet, the head guide, grumbled.

Henriette groaned, sat up, shook her head with indifference to her situation and then toppled back into her snow bed. Couttet swore under his breath. One of the younger guides boldly stepped forward, and, with the intent to appeal to Henriette’s pride and extreme aversion to any form of failure, he bent down close to her face, questioning, “Should I carry her? I can do it. I’m still strong enough.”

His offer penetrated Henriette’s consciousness. She rose to her knees, grabbed her hiking stick, and hosted herself up on unsteady feet. “I will not be carried!” she exclaimed as the glint returned to her eyes. She turned to face the snowy slope. “I intend to make the whole journey on my own two feet. Truly there would not be much merit in going up Mont Blanc on someone else’s back!”

To the male guides who accompanied Henriette d’Angeville as she stubbornly reached the summit of Mont Blanc in 1838, her achievement marked a turning point in mountaineering history. Henriette’s accomplishment helped to break through the age-long belief that the “fairer sex” could not endure the strenuous activity of mountain climbing nor could their “weaker constitutions” survive in harsh climates and thin, oxygen-depleted environments. Although Henriette’s achievement on Mont Blanc is today little-known, societal perceptions of what women could achieve in the outdoors began to crumble in the nineteenth century.

True to the pioneer spirit that settled North America, women set out with a determination to experience mountain adventures on this continent. History reveals that they were not following in Henriette’s footsteps but rather preceding her Mont Blanc accomplishment by nearly seventeen years. Particularly in the northeastern region of the United States, several accomplishments by women in many ways rival that of Henriette’s and helped to set the stage for female participation in projects such as the Appalachian Trail and in hiking organizations such as the Appalachian Trail Conference and its maintaining clubs. From the Austin sisters’ summit of New Hampshire’s Mount Washington in 1821 to the ascent of Maine’s remote Katahdin by Hannah Keep and Esther Jones in 1848, American women were raising “the glass ceiling” on this side of the Atlantic Ocean.

Just as the French hailed each successful assent of Mont Blanc, the earliest American adventurers to be considered mountaineers regarded New Hampshire’s Mount Washington with awe and trepidation. (Darby Field took two Abenakis on two superstition-busting treks to the summit in 1642.) Since an ascent by an all-male group of scientists in 1784, Mount Washington has held tenaciously on to its reputation for changeable, severe weather. Manassed Cutler, who offered the most detailed account of the 1784 expedition, agreed with the calculation of Mount Washington’s height as close to ten thousand feet—an over-estimation of nearly four thousand feet. And, at the time, he could list only four peaks in the world higher—Andes, Peak of Teneriffa, Gamoni, and the notorious Mont Blanc. Accordingly, when three young sisters, Eliza, Harriet, and Abigail Austin, visited the guest house of Ethan and Lucy Crawford in New Hampshire’s White Mountains in August 1821, the Crawfords were not quite prepared to welcome this new breed of female adventurer.

After losing their first home in the notch between Mount Webster and Mount Willey in the Presidential Range to a fire in July 1818, Ethan moved a small house to their home site and, over several years, expanded their home to serve as an inn for settlers transporting goods between the upper Connecticut River Valley and the seaport towns of Portland, Maine, and Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Ethan and Lucy soon found their inn welcoming hundreds of horse-drawn sleighs each week when snow covered the ground, as tradesmen hauled pork, cheese, butter, and other farm products through the notch and on to New England markets. With the notion of further expanding his business by promoting the area’s mountains as a place for outdoor adventure, Ethan and his father, Abel, cut a primitive trail to the summit of nearby Mount Washington.

In the spring of 1821, Ethan, assisted by a young surveyor, blazed a much-improved path to Mount Washington’s summit. Soon afterward, the Crawford inn began welcoming more and more refined city-dwellers who were seeking adventures in the White Mountains under the relative comfort and safety of local guides such as Ethan and other Crawford men. Although early groups all consisted of male adventurers, Ethan’s notoriety as “the mountain giant” capable of conquering the area’s peaks and Lucy’s fame for making her guests comfortable and well-fed soon attracted tourists of the “fairer sex,” such as the Austin sisters.

Each newly cut trail improved access to the once-remote summits within the White Mountains, quite naturally inviting adventuresome women to do more than gaze upon these lofty heights from the comfort of the Crawford inn. No longer feeling the traditional restrictions to watch as husbands, brothers, sons, and fathers set out at dawn for mountain adventures nor to listen as they returned home at dusk boasting of their mountaineering prowess, women guests began requesting that the Crawfords guide them to the nearby summits.

On August 31, 1821, when Eliza, Harriet, and Abigail Austin arrived at the Crawfords’ Old Moosehorn Tavern with the intent to become the first women to walk to the summit of Mount Washington, Ethan just recently had completed his second path to its summit. However, suffering from a recent ax wound to his heel, he was not prepared to serve as guide. Instead, two local men served as guides—Charles Stuart, a veteran of one year’s climbing experience, who was engaged to Eliza, and a tenant of the Austin farm who was to carry the ladies’ baggage. Their brother, Daniel Austin, would also accompany them.

The Austin sisters were not experienced hikers, nor were they inclined to abandon their long skirts, which caught on the rocks and roots of the newly cut, seven-mile approach trail and became heavy with rain as they spent two of their three nights at the same primitive camp while waiting out a storm. Despite those days of floundering on the approach trail and requiring Ethan to eventually hobble on a cane to come to their assistance, Eliza, Harriet, and Abigail each reached Mount Washington’s summit on the fourth day. To the young sisters, their adventure was a success. However, to Ethan—and many other men, to be sure—the Austin sisters’ experience did not convince them that women were capable of true mountaineering. Nevertheless, over time, Ethan began to do what he could to make the climbing routes easier and safer. He built additional camps and improved the approach trails in order for hikers to face the final assents with greater reserves of energy. Finally, in 1825, his wife, Lucy, succeeded in accompanying Ethan to the summit of Mount Washington, and, by the late 1820s, women were no longer a rarity on many peaks across the White Mountains.

Eliza, Harriet, and Abigail Austin were most likely the first women in the United States to climb a significant mountain. Along with their French mountaineering counterpart, Henriette d’Angeville, the Austin sisters were pathbreakers both in physical accomplishments and social barriers. Yet, even as women began to trickle into America’s mountainous regions and hiking communities, their acceptance was cautiously slow. A journal entry in the Crawford guesthouse registry states:

Gentlemen, there is nothing in the ascent of Mount Washington that you need dread. Ladies, give up all thought of it; but, if you are resolved, let the season be mild, consult Mr. Crawford as to the prospects of the weather, and with every precaution, you will still find it, for you, a tremendous undertaking.

Despite such cautions, women continued to reach the summits of many of America’s northeastern mountains. Mrs. Daniel Patch made the ascent of Moosilauke around 1840, enjoying a proper brew of tea on the summit from the teapot she carried to the top. A year earlier, in New York’s Adirondack Mountains, a fifteen-year-old farm girl, Esther McComb, defied the prohibitions of her parents as she set out for the summit of Whiteface. She never made it to Whiteface but rather was rescued by a search party after climbing what later was named Mount Esther—still a noteworthy, mountaineering accomplishment by a young, inexperienced farm girl.

The Austin sisters were not experienced hikers, nor were they inclined to abandon their long skirts, which caught on the rocks and roots of the newly cut, seven-mile approach trail.In August 1849, two groups of female climbers competed to become the first women to reach the summit of Maine’s Katahdin. In retrospect, that particular objective has clear connection to the yet-to-be-conceived Appalachian Trail, since, as that project evolved nearly seventy-five years later, Katahdin would come to be identified as the northern terminus of this long-distance through-trail following the Appalachian Mountains.

When five women under the leadership of a “forceful and prickly” Marcus Keep set out for Katahdin’s summit in the summer of 1849, local resentment was aroused. A second female party consisting of Mrs. E. Oakes Smith, an accomplished mountaineer, and two men took on the challenge of depriving Keep’s group of the notoriety of taking the first women hikers to Katahdin’s summit. A women’s race to the summit ensued.

On August 11, Mrs. Smith and her fellow hikers reached what they declared to be the “Top of Mount Katahdin,” as they stated quite arrogantly in a note left for the Keep party to discover a week later. Keep and his group of five women, upon finding the note, continued undisturbed across the Knife Edge, where he later wrote, “no foot of better halves had been,” then proceeded to reach South Peak. From there, Hannah Taylor Keep and Esther Jones continued to the last summit of the ridge, which is today regarded as Katahdin’s true summit. There, the two women piled rocks upon rocks to mark their accomplishment. It is quite possible that the cairn they built that day was the first constructed on that summit and serves as the forerunner of the iconic cairn that stands today at the northern terminus of the Appalachian Trail.

Justifiably, the footprint those two women left at the summit of Katahdin was more than a simple, feminine presence. Perhaps it was the genesis of an Appalachian Trail legacy that has endured to this day. In either case, on August 20, 1848, Hannah Keep and Esther Jones’ ascent of Katahdin earned them a place in women’s mountaineering history, and their simple actions of placing rock upon rock on Katahdin’s summit arguably made a significant contribution to the role of women in Appalachian Trail history.

Barriers still existed for women determined to be a part of America’s growing interest in the outdoor activities of hiking and mountain climbing and the expanding formation of trail clubs. But, the accomplishments of those women in New Hampshire’s White Mountains, and others continents away, such as Henriette d’Angeville, were disproving all traditional perceptions of the “fairer sex’s” mental and physical limitations. As Lucy Crawford would later write in her History of the White Mountains, regarding the Austin sisters, but also descriptive of these women pioneers of hiking:

I think this act of heroism ought to confer an honor on them, as everything was done with so much prudence and modesty by them: There was not left a trace or even a chance for a reproach or slander excepting by those who thought themselves outdone by these young ladies.

Lucy and her contemporaries were not yet ready to throw off their long skirts in favor of more sensible hiking attire, such as bloomers or slacks, but the stage was set for women in greater numbers to take to the mountains—especially in the more progressive, urban areas surrounding the eastern Appalachian Mountain range. No longer content to sit on the Crawford Inn’s porch and gaze upward at lofty mountain peaks, women were now determined to experience the sublime.

__________________________________

From We Were There, Too by Gwenyth Loose. Used with the permission of Mountaineers Books. Copyright © 2020 by Gwenyth Loose.